The youngest voice on a Paris stage Friday had an especially compelling call for the world to act quickly and decisively to end the global plastics crisis.

That message came from Betty Osei Bonsu, representing the Green Africa Youth Organization, a nongovernmental group, who will be attending next week’s second negotiation session of the United Nations’ effort to develop a legally binding treaty to curb plastic pollution.

“We want to see a just transition to safer and more sustainable livelihoods for workers and communities across the plastics supply chain,” Bonsu told the pre-negotiation gathering that included United Nations officials, delegates from countries large and small and business leaders.

She called for a global agreement that will hold “corporate polluters responsible for the profound damages that is caused by excessive production of plastics,” and said: “We need global leaders to stand up for this fight.”

Bonsu took head-on the chemical industry’s big push for so-called “advanced” or “chemical” recycling, touted by lobby groups such as the American Chemistry Council as a way to use technology such as pyrolysis or gasification to turn plastic waste into fuel or feedstocks for new plastics.

“No more techno-fixes and false solutions such as chemical recycling or incineration,” Bonsu said, echoing criticism by some scientists and other environmentalists who have said chemical recycling is a largely unproven technology that requires too much energy, has questionable climate benefits and puts communities and the environment at further risk from toxic pollution. “These are only perpetuating our addiction to plastics,” she said.

Bonsu is from Ghana and serves as the Uganda country manager for the Green Africa Youth Organization, a youth-led and gender-balanced advocacy group that focuses on environmental sustainability and community development.

Her work includes advancing green jobs for rural communities and youth engagement in climate policies while she is pursuing a master’s degree at the United Nations University, a global think tank headquartered in Japan, studying environmental risk and human security.

Bonsu was among 11 people who spoke at Friday’s briefing, which was organized by World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Waste, the Scientists Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty and the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty, in advance of s next week’s negotiation. Delegates are hoping to begin to coalesce around some of the major themes of, or expectations for, a draft treaty.

Bonsu told delegates and others that “young people are recognizing the fact that they are the ones who will be most affected by plastics pollution, particularly those of us residing in the Global South, who are already experiencing the adverse effects of climate change, plastics pollution and biodiversity loss. We need urgent action.”

Last year, 175 nations agreed to find a way to stop future plastic production from choking ocean and land ecosystems and to clean up legacy plastic pollution. They set a goal of reaching an agreement by the end of next year.

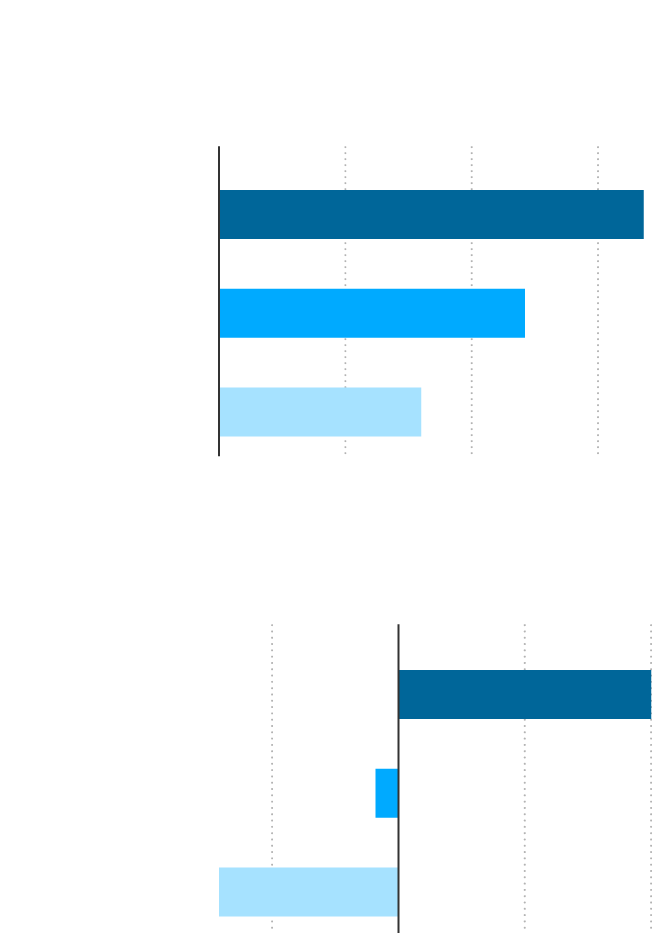

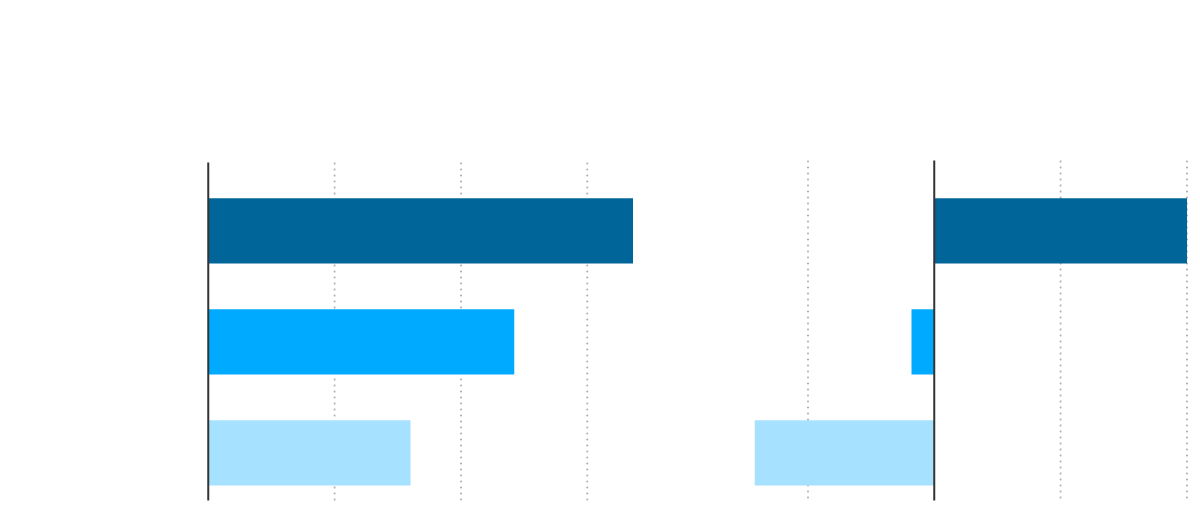

In the run-up to next week’s talks, the United Nations Environment Program released one report that detailed the toxic threats from the thousands of chemicals used to make plastic and another that identified a roadmap of potential solutions to cut plastic waste by 80 percent.

Environmentalists, businesses and scientists are also weighing in, issuing reports, statements or letters in efforts to influence the talks, including policy briefs from the Scientists Coalition, a nongovernmental organization based in Norway, on plastics and chemicals, and climate change.

Greenpeace USA also published a report that seeks to make a case that recycling increases the toxicity of plastics.

In March, research published by the Annals of Global Health, a peer-reviewed journal, concluded that plastic causes illness and death across its lifecycle, from production to use and disposal.

The risk can come from being near oil and gas extraction, working in plastic manufacturing plants or living near them, eating food heated in plastic packaging or breathing the air near incinerators where plastic waste gets burned as trash.

The Plastic Industry Association, a lobby group, issued a statement proclaiming the benefits of plastic, calling it “essential to the health, safety, protection and well-being of humanity,” and arguing against limits to plastic production that, it said, would “stifle” innovation. Instead, the business group said, the focus should be on fostering an economy where plastic waste “is valued for what it can achieve.”

The American Chemistry Council’s Joshua Baca said Greenpeace’s proposals “would disrupt global supply chains, hinder sustainable development, and substitute plastics with materials that have a much higher carbon footprint in critical uses.”

A number of countries or coalitions of countries have already put forward their initial positions for the meeting, dividing along certain fault lines. In all, the U.N. has collected more than 60 opening submissions from participating countries, and another 200 written comments from non-governmental organizations, including environmental and business groups.

Some of the countries’ opening proposals are strong and expansive. The European Union, for example, calls for global targets to reduce the production of plastics. The EU and other countries articulate their vision for phasing out risky chemical additives, such as endocrine disruptors like phthalates, which are used to make plastics pliable and are a threat to human health.

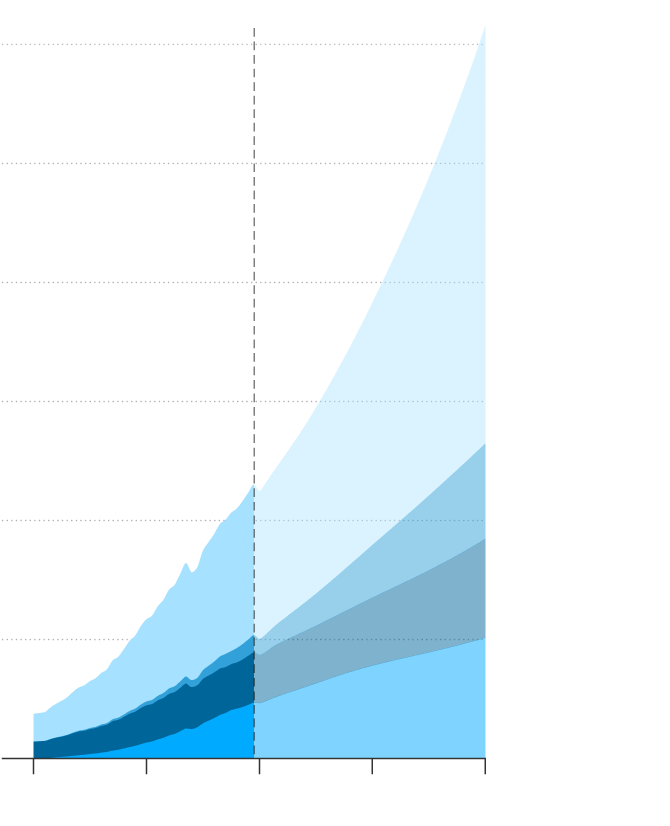

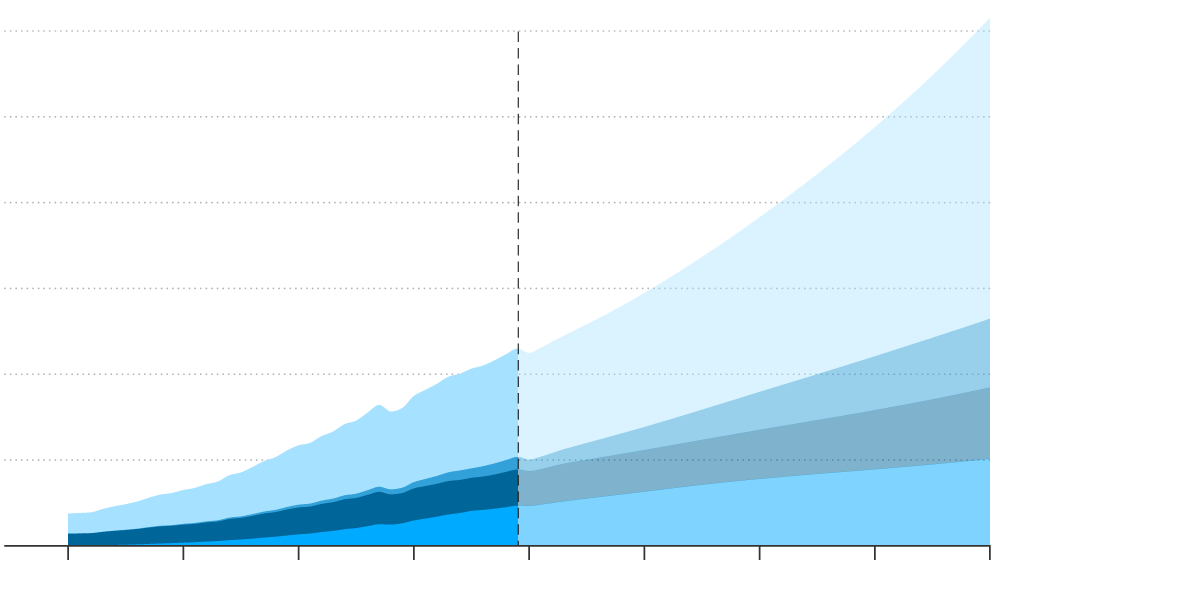

The growing, 55-member High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution, led by Norway and Rwanda, offered a proposal that notes plastic consumption has quadrupled over the past 30 years and that plastic production would likely double over the next 20. Measures and targets for limiting plastic production will be needed to “reduce pressure on the environment globally,” they wrote.

Critics have described the Biden administration’s opening position as weak and vague, or “low ambition,” despite its recognition of a need to end plastic pollution by 2040. It calls for individual national action plans as opposed to strong global mandates.

Friday, a U.S. delegate from the State Department, Jose W. Fernandez, sought to convey the United States’ commitment to solving the plastics crisis.

“Let me start with a clear message,” said Fernandez, the under-secretary for economic growth, energy and the environment in the Biden administration. “Solving the plastic pollution crisis is a priority for the United States,” he said. “The United States is one of the largest producers and consumers of plastic. And we’re also one of the largest generators of plastic waste. We know that the world is watching our actions. And we are determined to lead by example.”

For its part, the High Ambition Coalition, which includes the European Union, Canada and Japan, issued a new statement on Friday that called for a “comprehensive approach that addresses the full lifecycle of plastics, with a view to end plastic pollution by 2040 to protect human health and the environment from plastic pollution while contributing to the restoration of biodiversity and curbing climate change.”

The coalition called for several binding provisions including those targeting microplastics, which have become ubiquitous in the environment and are found in human blood, placental fluid and feces, and to remediate existing plastic pollution.

Espen Barth Eide, the minister of climate and the environment for Norway and the co-chair of the coalition, said its efforts should be seen as focused on stopping plastic waste, not combatting plastic.

“As such, we realize that there will be products that will still be made by plastics,” he said. “We realize that that can be done in a much sounder way than today. But we do also recognize that we will have to substitute plastics in certain products, we have to come to an end with the use of single-use plastics, we have to think about reusability and recyclability and in order to do that, we also have to look at the product design.”

Plastic was never designed to be recycled.

That will have to change, he said, adding: “That plastic that shall still be used will need to be designed from the start in such a way that re-use, and later, if necessary, recycling, is possible and sound and healthy.”

James Bruggers

Reporter, Southeast, National Environment Reporting Network

James Bruggers covers the U.S. Southeast, part of Inside Climate News’ National Environment Reporting Network. He previously covered energy and the environment for Louisville’s Courier Journal, where he worked as a correspondent for USA Today and was a member of the USA Today Network environment team. Before moving to Kentucky in 1999, Bruggers worked as a journalist in Montana, Alaska, Washington and California. Bruggers’ work has won numerous recognitions, including best beat reporting, Society of Environmental Journalists, and the National Press Foundation’s Thomas Stokes Award for energy reporting. He served on the board of directors of the SEJ for 13 years, including two years as president. He lives in Louisville with his wife, Christine Bruggers.