Obesity is on the rise almost everywhere, with more overweight and obese than underweight people, globally. According to accepted wisdom, blame lies squarely with overeating and insufficient exercise. A small group of researchers is challenging such ingrained assumptions, however, and shining a spotlight on the role of chemicals in our expanding waistlines.

‘There are at least 50 chemicals, probably many more, that literally make us fatter,’ says Leonardo Trasande, an environmental health scientist at New York University in the US. An obesogen is a chemical that makes a living organism gain fat. Notable examples include bisphenol A, certain phthalates and most organophosphate flame retardants. They can push organisms to make new fat cells and/or encourage them to store more fat. Almost all of us often encounter such chemicals every day.

Over the past 20 years, calorie consumption is flat – but obesity has gone up

This may even help explain some discrepancies in data. Obesity rates have tripled since the 1970s, ticking up in the US from 30.5% in 2000 to 42.4% in 2018. ‘Over the past 20 years, calorie consumption is flat, or gone down slightly [in the US],’ according to Bruce Blumberg, a cell biologist at the University of California Irvine in the US. ‘But obesity has gone up.’ And it is not just humans. Body weights of animals such as dogs, cats, rodents and non-human primates – in research colonies and living feral – are also reported to be increasing. Blumberg and others are on a mission to persuade clinicians and others to take contributions to obesity from chemicals more seriously.

Weight gain

The hypothesis that chemicals encourage weight gain is perhaps not surprising, given that an expanded waistline is a side effect of some medicines. Antidepressants such as selective serotonin receptor inhibitors are associated with weight gain, and anti-diabetic drugs such as rosiglitazone were long known to add a few pounds.

Blumberg coined the term obesogen in 2006, when his lab showed that tributyltin chloride promoted fat formation in mice. ‘Mice we expose to tributyltin don’t eat more, and they don’t exercise less than animals not exposed to it,’ says Blumberg. ‘But they use calories differently – they store more as fat. That’s very relevant to humans.’ Exposure in utero leads to ‘strikingly elevated lipid accumulation’ in fat deposits, liver and testis of in neonate mice. Another early study showed that an estrogen drug (diethylstilbestrol) in pregnant mice significantly increased body weight of their offspring – as adults.

Starvation was a constant threat to our ancestors. ‘Weight gain is important to the survival of the species,’ says Robert Lustig, emeritus professor of endocrinology at the University of California, San Francisco, and campaigner against childhood obesity. ‘There are multiple paths to it.’ Some obesogenic chemicals flick biochemical switches to store fat for a rainy day.

Lusting and others described obesogen exposure as an underappreciated and understudied factor in the obesity pandemic, in a recent review of causal links.1 Dozens of animal studies are cited. Studies revealed, for example, that mice fed DEHP (bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate) consume more food, pile on weight and store more belly fat. We couldn’t ethically give people DEHP, but people are nonetheless exposed to it every day: it improves the flexibility of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and is used in floor and wall coverings, food containers, toys and cosmetics.

While you can’t dose people, you can analyse blood for chemical contaminants. Those with high phthalate levels are more likely to gain weight over the next 10 years, research has shown. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) – so-called forever chemicals – are also obesogens. They are villains in a clinical trial in the US (POUNDS Lost) investigating weight loss in 600 overweight and obese adults on one of four diets. Plasma concentrations of PFASs did not influence weight loss during six months of dieting, but women with high levels at the start of the trial experienced significantly more weight regain.

Mechanisms

Fat tissue expands due to increased cell number and size during foetal development, childhood and adolescence, while fat cell (adipocytes) numbers remain stable during adulthood, so long as weight remains stable. The primary regulator of fat cell formation (adipogenesis) is considered to be peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPAR-).

If you express this receptor on a mesenchymal stem cell, it becomes a pre-adipocyte, which are important cells that can become bone cells, immune cells or fat cells. If PPAR- then becomes activated by long-chained fatty acids, it becomes a fat cell. When triggered inside an existing fat cell, the cell accumulates more fat. ‘If you activate the receptor well, with full agonists, then the cells generally become healthy white fat cells,’ explains Blumberg.

This receptor has a large promiscuous pocket that is vulnerable to hacking by multiple obesogenic ligands. One of Blumberg’s early discoveries was that tributylin activated PPAR-He later found that it hits two parts of PPAR- at the same time, making white fat cells good at storing fat, but not good at releasing it. ‘The worst thing you could have – an unhealthy fat cell that stores but doesn’t give up its fat,’ Blumberg explains.

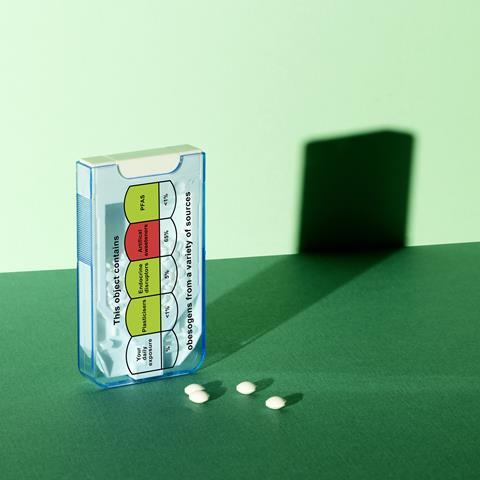

A long list of environmental contaminants bind to this fat receptor – plasticisers, phthalates and BPA and its analogues; flame retardants; and per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). All are obesogens. But this is not the only route. Obesogens can alter appetite control, impact the microbiome or change how much energy your body burns at rest (basal metabolic rate) via the thyroid hormone receptor, say researchers. Resting metabolic rate represents 70% of an average person’s energy expenditure, so lowering it has a major impact on weight. ‘People with the highest levels of perfluorinated chemicals have lower resting metabolic rates, a study has shown, and regain weight more quickly,’ notes Blumberg.

Phthalates can change how the body processes a meal and turn it into fat

Also susceptible to obesogenic chemicals are oestrogen and androgen receptors, glucocorticoid receptors and the retinoid X receptor, which promotes fat cell formation and the proliferation of precursor fat cells. Bisphenol A and its analogues, says Blumberg, ‘can target probably a dozen different pathways in the body’, for example. In vitro, BPA influenced PPAR-and lipid accumulation, while exposing unborn male mice to low dose – but not high dose – BPA stoked up body weight, food intake and number of fat cells, as well as insulin regulation, the enzyme needed to control blood sugar.

Binding fat cell receptors, fully or partially, can even shift a person’s metabolism. ‘Imagine you’ve had a good workout, you’ve eaten a good protein meal, and you are thinking you are going to gain some muscle,’ says Trasande. But chemicals such as phthalates can ‘change how the body processes a meal and ultimately turn it into fat or carbohydrate instead’, he warns. This turns on its head the simplistic story of overeating fat leading to a flabby girth.

Calorie counting

The obesogenic community is adamant that calorie counting has led clinicians and the public astray. And they are starting to spread their beliefs to the medical community. If you relegate weight gain to simple maths, energy in and energy out, then you gain weight if you eat too much and exercise too little. This is the energy balance model, and its major premise is that a calorie is a calorie, and you must not end up with too many. ‘It’s about two behaviours, gluttony and sloth, and therefore if you are fat, it is your fault,’ Lustig sums up. But he says there’s little evidential support.

Another proponent of the obesogen hypothesis is Jerrold Heindel, formerly involved in grant funding decisions for environmental chemicals and disease at the National Institutes of Health in the US. He became interested in the early 2000 . Now retired, he was pivotal in the recent publication of three review papers summarising evidence on obesogens.

Like others, he is frustrated about current approaches to obesity. While exercise improves health, it does not cure obesity, and dieting results in weight loss that is rarely sustained. Yet clinicians remain focused on diets, drugs and surgery. ‘If all that worked, we should see a decline in obesity, but we are not seeing a decline at all. It’s going up, especially in children,’ says Heindel. What many nutritionists miss is a cause of increased eating, which is obesogenic chemicals that alter sensitivity to weight gain, he adds.

His colleague Lustig views energy storage as coming first and increased food intake following. ‘In this energy storage model,’ he says, ‘biochemistry comes first, then the behaviours.’ He arrived at this conclusion partly from a study of children cured of a brain tumour, but obese because a drug ramped up their insulin levels. This pushed energy into fat, leaving them lethargic and hungry.

Ubiquitous foes

Obesogens are ubiquitous in our environment. They are present in dust, water, processed foods, food packaging, cosmetics and personal care products, but also furniture and electronics, air pollutant, pesticides, plastics and plasticisers. Phthalates and organophosphates can be detected in around 90% of Americans, notes Chris Kassotis, a toxicologist at Wayne State University in Detroit, US. ‘They’re high-production chemicals, pretty ubiquitous, with high human exposure,’ he notes.

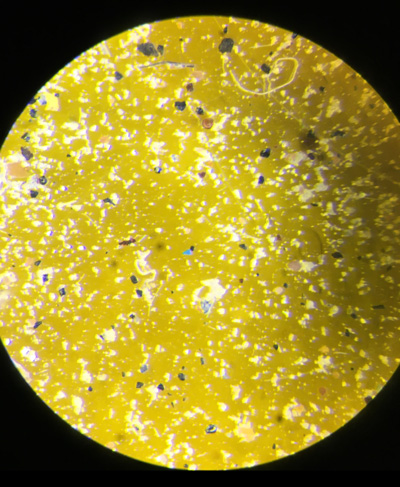

Kassotis has taken an interest in the finer things in life – specifically, house dust, a complex mixture of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of chemicals. In 2017, Kassotis reported that house dust impacted mouse fat cells. Ten of 11 extracts spurred triglyceride accumulation in preadipocyte mouse cells.

‘Really low levels of dust were able to drive the development of fat cells in our cell model,’ recalls Kassotis. Around 20μg of dust impacted the fat cells, a small amount considering the Environmental Protection Agency in the US estimates that a child consumes about 50mg of dust per day. A subsequent study found that about three-quarters of dust samples antagonised a thyroid receptor, and about one-fifth activated PPAR-Ultimately, the Karssotis lab tested over 350 samples and around 90% showed activity in mouse fat cells.

Environmental contaminants are not the only source. Many ingredients added to processed foods are sources too, say obesogen researchers. ‘When we add sugar to make a food taste better, we’re making it more obesogenic,’ says Blumberg. Table sugar, sucrose, consists of one glucose and one fructose unit, with fructose found naturally in fruit, honey, and root vegetables. Fructose is the most concerning, as far as Lustig is concerned. ‘It inhibits mitochondrial function, which is necessary to burn energy,’ he explains. ‘If you don’t burn it, then it gets turned into fat and stored.’

Fructose was traditionally consumed around harvest time, a natural signal for the body to store fat in the liver in preparation for the coming winter, says Lustig: ‘This makes evolutionary sense, but the problem is that it is now available all the time.’

Some foods advertised as low calorie or for weight loss may contain obesogens. ‘Diet sweeteners cause weight gain,’ asserts Lustig, ‘because they raise your insulin levels.’ Research in animals and humans show a positive link between insulin levels and obesity. The addition of artificial sweeteners such as aspartame, saccharin and sucralose to foods has successfully reduced sugar intake, but not obesity levels.

In one study, children born to mothers in Canada who regularly consumed non-nutritive sweetened drinks had a higher body mass index and more fat tissue by age three. The researchers then fed sucrose, aspartame or sucralose to pregnant mice. Male mice born to mothers on aspartame and sucralose showed body fat rises of 47% and 15%, respectively.

Also suspected to be obesogens are the flavour enhancer monosodium glutamate, food emulsifiers such as dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate, and parabens used as preservatives in foods and in personal care products. Some food additives such as carboxymethylcellulose are believed to increase body weight – at least in mice – by altering the microbiota in the gut. The additive thickens foods and stabilises emulsions such as in ice cream products. Reducing exposures to such common substances will be challenging.

Although there is widespread evidence from animal models, some experts in other fields like toxicology are not fully convinced. They make the point that environmental obesogens like these are generally low potency, which when combined with low exposures to most people, means there is very low risk. And with controlled experiments difficult to carry out in humans, they may remain unconvinced. Obesogen researchers counter that many scientists don’t yet fully consider endocrine disruptors to be important factors.

Regarded safe

Regulation is also a struggle. ‘We operated under the assumption that only the dose makes the poison,’ says Trasande. This has allowed endocrine-disrupting chemicals – of which obesogens are a subset – to dodge regulations because their effects can be subtle and occur at low doses. Parts per billion of tributyltin influence snails and fish. The same is true of fat cells. ‘Tributyltin causes effects at doses which people are exposed to, such as 20ppb,’ says Blumberg. ‘You can make animals obese at those levels.’ This sets a high bar from those in the field who wish for policy action against these chemicals. ‘[Researchers] are findings effects below the doses that governments say is safe for many of these chemicals,’ warns Heindel.

There are hundreds of endocrine-active chemicals in plastics

Also, many food additives that are obesogens or suspected obesogens are designated ‘generally regarded as safe’ by the Food and Drug Administration in the US. This applies to a substance used in food prior to 1958 or with a substantial history of consumption. ‘They were never tested,’ says Blumberg, ‘but regulators should go back and test them.’ The recent proposal by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to lower the reference dose of BPA 100,000-fold is a case in point, according to Blumberg – ‘it brings it into line with what the endocrine disrupting community has been saying for years’. Such ‘innocent until proven guilty chemicals’ are a problem, warns Trasande.

Consumers, nevertheless, can reduce their exposures. Among suggestions are to reduce use of plastic containers and packaging, and never microwave with plastic. ‘Do not eat packaged processed food. It’s full of obesogens. Buy fresh ingredients and make a meal,’ advises Blumberg. A Norwegian study found that one-third of the chemicals in 34 plastic consumer products disrupted the development of fat precursor cells in vitro. Analyses revealed a motley assortment of additives, breakdown products and manufacturing residues. ‘There are hundreds of endocrine-active chemicals in plastics,’ says Blumberg. Glass is a healthier alternative, he adds. According to Trasande, studies show that reducing canned food consumption reduces blood bisphenol levels. Cast iron and stainless steel are alternatives to nonstick cookware, which is made using PFOA.

Assessing how much chemicals may be contributing to the obesity epidemic is difficult. ‘There’s a tip of the iceberg phenomenon. There’s what we know, and what we don’t know, but the evidence is evolving,’ says Trasande. It is not that obesogens are the cause of the obesity pandemic, but a contributing factor. There is little monitoring of chemical levels within people, and government action is needed here. ‘We need to know who is exposed and what the critical times of life are,’ says Blumberg. Once programmed to have a certain number of fat cells, you will never have less.

Unfortunately, there are worrying signs of possible impacts running down generations. Mice whose grandparents were exposed to tributyltin in utero are affect. One study showed mother mice exposure to low doses of tributyltin during pregnancy predisposes (unexposed) male mice in the fourth generation to obesity via a so-called ‘thrifty phenotype,’ meaning a propensity to store fat and hold onto it during fasting. ‘We don’t have human data for transgenerational effects yet, but you can see how scary that would be,’ says Heindel. ‘Increased obesity in children is still due to poor diet and exposure during pregnancy and childhood, but maybe some of that exposure was through their grandmother.’

While obesogens are not the sole cause of the obesity problem, these chemicals deserve more attention and potentially stricter regulation. And those advocating action say that the obesogen hypothesis offers a preventive approach, so that reducing exposures should reduce the incidence or severity of obesity.

Anthony King is a science writer based in Dublin, Ireland