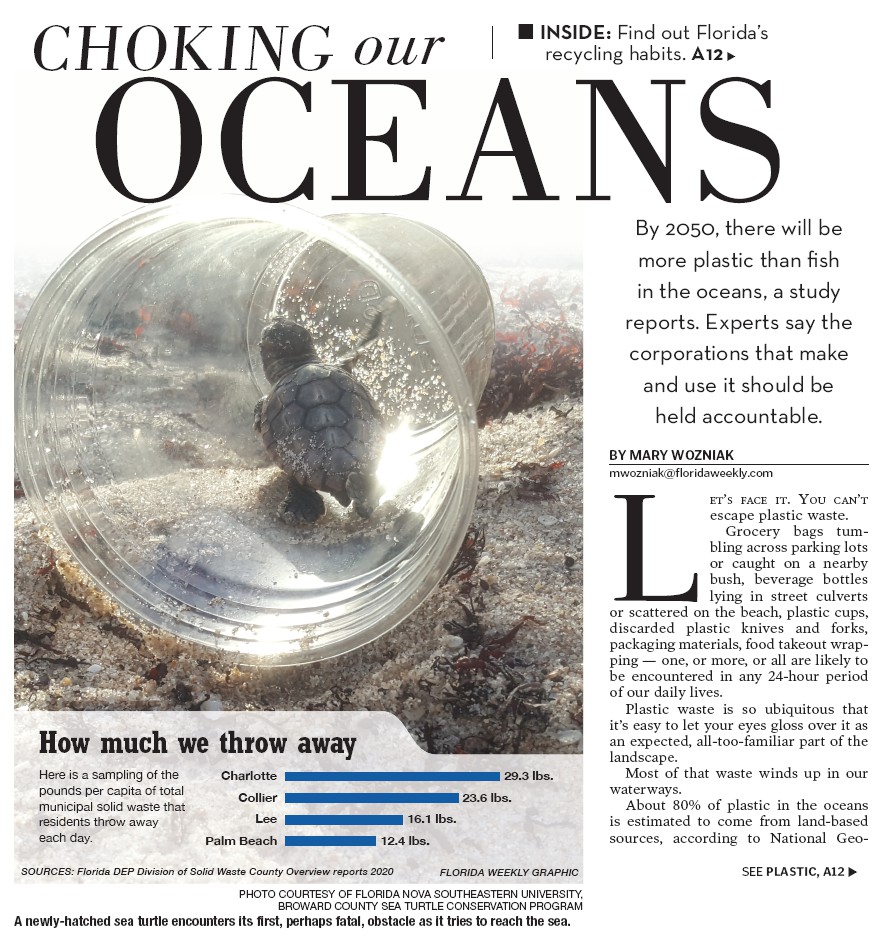

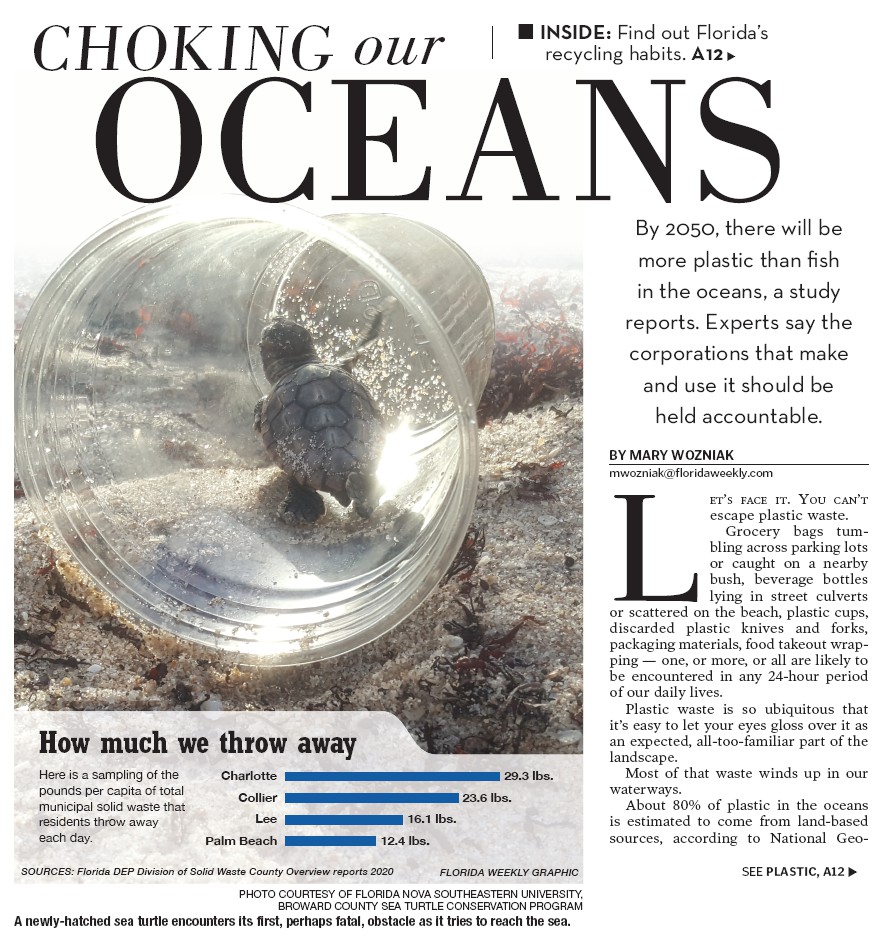

A newly-hatched sea turtle encounters its first, perhaps fatal, obstacle as it tries to reach the sea. PHOTO COURTESY OF FLORIDA NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY, BROWARD COUNTY SEA TURTLE CONSERVATION PROGRAM

LET’S FACE IT. YOU CAN’T escape plastic waste. Grocery bags tumbling across parking lots or caught on a nearby bush, beverage bottles lying in street culverts or scattered on the beach, plastic cups, discarded plastic knives and forks, packaging materials, food takeout wrapping — one, or more, or all are likely to be encountered in any 24-hour period of our daily lives.

Plastic waste is so ubiquitous that it’s easy to let your eyes gloss over it as an expected, all-too-familiar part of the landscape.

Most of that waste winds up in our waterways.

About 80% of plastic in the oceans is estimated to come from land-based sources, according to National Geo- graphic. A study by the World Economic Forum estimates that by 2050, there will be more plastic than fish in the oceans.

A plastic bag is used for an average of 12 minutes, but it can last in the environment for several hundred years. Plastic waste has been found in Antarctic ice and the deepest part of the ocean. Researchers found a plastic bag in the Marianna Trench in the Pacific, 36,000 feet deep.

The problem is global, but the actions needed to fight it filter down to the national, state and local level. Mainly, the actions need to come from new government policy that holds the corporations that make the plastic and the manufacturers that use it accountable for the pollution it causes, scientists and environmentalists say.

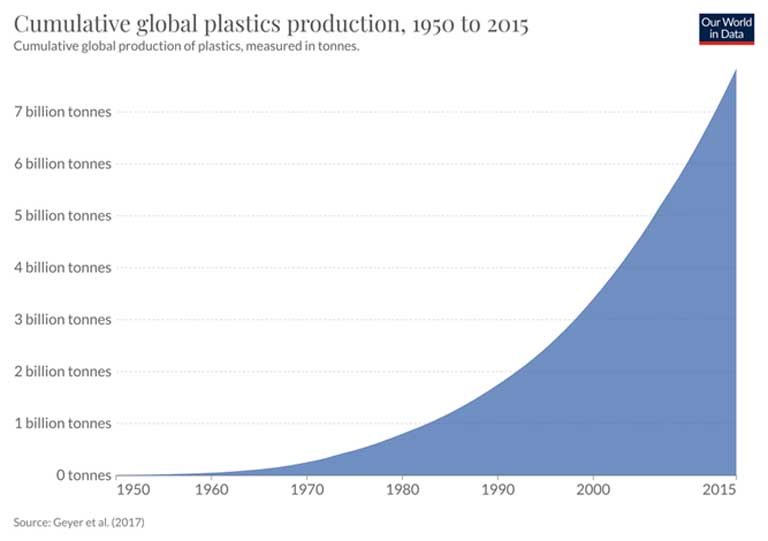

“Plastics are extremely cheap to produce and incredibly durable,” said Jennifer Jones, associate professor of environmental studies and director of the Center for Environment and Society at Florida Gulf Coast University. “That means we’re creating a ton of something that never really goes away. Every piece of plastic we’ve ever made still exists and the plastics industry has convinced us this is OK because we recycle. The truth is, recycling isn’t going to save us. With plastic production set to triple by 2050, only stopping plastic production will.”

JONES

The rising tide of plastic waste doesn’t bode well for Florida, with its $90 billion tourism economy largely focused on the lure of white sand beaches, warm waters, tropical sunshine and all the recreation that goes along with it. Florida is surrounded on three sides by water, with 8,436 miles of coastline. It’s a big coast, which means the threat caused by plastic pollution is disastrous.

Add in 55,000 miles of rivers and streams, plus lakes, estuaries and wetlands and the problem is amplified.

Ecotourists hope to see frolicking dolphins, maybe a glimpse of a sea turtle or a tiny hatchling scurrying toward the sea, the nose of a gentle manatee breaking the water’s surface, wading birds feasting on fish and other marine morsels, nesting shorebirds.

Plastic bags, plastic bottles, plastic cups and plastic wrappings are not part of the idyllic scenario. These are the single-use plastics that are the main culprits — cheap plastic goods that are used once and thrown away.

WARNER

Damage done

Scientists estimate that 15 million metric tons of plastic wash into the oceans every year. That equates to about two garbage trucks’ worth of plastic entering the oceans every minute.

Once it gets washed into waterways, it causes at least $13 billion annually in damage to marine ecosystems and about $2 billion in losses for tourism (just looking at the Asia-Pacific area and Europe), The World Economic Forum study said. “In addition to direct economic costs, there are potential adverse impacts on human livelihoods and health, food chains and other essential economic and societal systems.”

Florida put an estimated 7,000 tons of plastic waste into its marine environments in 2020, according to a study done for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. That’s not counting the amount collected in thousands of cleanups held by environmental and civic organizations.

BASSETT

The impact of plastic waste on marine life is clear.

A 2020 study by Oceana, a nonprofit ocean advocacy group founded by Pew Charitable Trusts and other foundations, attempted to compile for the first time the available data on plastic ingestion and entanglements in marine mammals and sea turtles in U.S. waters. The study, titled “Choked, Strangled, Drowned: The Plastics Crisis Unfolding in Our Oceans,” surveyed dozens of government agencies and organizations. The study found that sea turtles, manatees and other marine life off the coast of Florida made up 55% of the animals who were injured or killed by plastic pollution.

“I think Florida is kind of unique,” because of its long coastline, said Kimberly Warner, study co-author and senior scientist at Oceana. “So many endangered, threatened species call Florida home.”

When marine animals encounter plastic they may ingest it inadvertently or mistake it for food. They can get entangled in it. Their intestines can be lacerated. They can drown or choke to death. The plastic in their stomachs can make them feel so full that they stop feeding and die of starvation. If plastic waste twists around a fin or other extremity, the need for amputation can result.

McGEE

In the Oceana study, Brandon Bassett, a biologist at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, said that roughly one in 10 manatee carcasses contains some sort of marine debris. He recounted one particular case of a manatee that died after ingesting a large amount of plastic waste.

“Imagine a ball of plastic bags in the stomach, about the size of a cantaloupe, and then a bunch of plastic bags that were wrapped and almost like a rope that was about 3 feet long,” Mr. Bassett said.

“On the other end of that was another ball of even more plastic bags that was maybe about half the size of a cantaloupe, and that was in the intestine. That whole mass ended up killing the animal. Stuff like that can lead to not only death, but significant and unnecessary suffering.”

SHORT

The FWC provided all its datasets to Oceana for the study, said Jenn ifer McGee, FWC marine debris coordinator. She handles marine debris from plastics to derelict vessels to discarded monofilament fishing line, deadly to birds and other animals.

She noted a study on the FWC website in which researchers went over 6,500 manatee necropsy reports over 20 years (1993-2012) and found more than 11% of the animals that died either ingested or showed evidence of entanglement in marine debris.

Nearly 100% of sea turtles they see have also ingested plastic, she said. FWC has been working with partner agencies, environmental groups and their own marine planning team to compile data and put together the state Marine Debris Reduction Plan.

Ninety percent of seabirds eat plastic and 100% will be consuming it by 2050, a study published in 2015 in the National Academy of Sciences by lead researcher Chris Wilcox and others found.

A manatee lies dead at the water’s edge amid an assortment of plastic waste. PHOTO COURTESY OF SOUTH FLORIDA 4 OCEAN

Shorebirds are also impacted by plastic waste, said Holley Short, shorebird program manager for Audubon Florida.

“Unfortunately, I see plastic waste frequently at our nesting bird sites,” she said. The number of photos she receives from her volunteers showing birds interacting with plastic waste is “overwhelming,” Ms. Short said.

“I primarily see this trash on public beaches,” she said. So the birds nesting on these beaches and trying to raise chicks not only have to deal with human activity, but the trash they leave behind, she said.

Plastic is not biodegradable. It lasts for hundreds of years. But it does break down into tiny microscopic pieces, no more than 5 millimeters long, called microplastics. They are eaten by fish and other marine life and eventually make their way up the food chain to us.

A World Wildlife Federation analysis assessing plastic ingestion from nature to people points to a study by the University of Newcastle in Australia, which estimates the average person may be ingesting about 5 grams of plastic every week. That’s a credit card’s worth of microplastics.

A black skimmer finds a plastic fork on the beach. About 7,000 tons of plastic waste ended up in marine environments in Florida in 2020. PHOTO BY AUDUBON FLORIDA VOLUNTEER BETH REYNOLDS

Climate change nexus

Plastic was first introduced in the early 1950s.

More than 98% of plastic is made from fossil fuels, a product of the oil and gas industry.

As of 2019, 4% to 8% of global oil consumption is linked to plastics, according to the World Economic Forum. If this persists, by 2050, plastics will account for 20% of oil consumption.

There is an important nexus between the plastic waste crisis and the climate change crisis, said Michael Mann, distinguished professor of atmospheric science and director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University

He was a panelist at a Feb. 16 webinar called “Don’t Look Down: How Misinformation & Science Denial Obscures the Global Plastics and Climate Crisis,” The webinar was held by the Plastic Pollution Coalition, a global alliance working toward a world free of plastic pollution. Mann’s work has provided inspiration for Leonardo DiCaprio’s character in the satirical film “Don’t Look Up,” the coalition says.

MANN

“We have these common villains when it comes to the global plastic pollution problem and the climate problem, the climate crisis,” Mr. Mann said. “In both cases we are dealing with decades-long disinformation campaigns by the petrochemical industry and fossil fuel industry aimed at discrediting the science, fooling the public and diverting attention away from the need for real policy solutions” he said.

Instead, they try to deflect responsibility for plastic pollution to the actions of the individual consumer, he and other scientists say.

As a prime example of the deflection, they point to the Keep American Beautiful campaign, also created in the early 1950s, with founding members including The Coca-Cola Company, Pepsico, Philip Morris, the Dixie Cup Company and Anheuser-Bush, among others from the beverage and packaging industries.

A plastic ring encircles a bottle nose dolphin calf. PHOTO COURTESY OF FLORIDA CLEARWATER MARINE AQUARIUM

They wanted to defeat the bottle bills that were coming up in various states, a policy solution that would actually do something meaningful about the problem, Mr. Mann said. But it would hurt their bottom line, as they would be forced to process the returned bottles and cans. Instead they engaged in a massive campaign “aimed at convincing us that we didn’t need policies, we didn’t need bottle bills, we just needed to be better individuals,” Mr. Mann said. “It was on us.”

The campaign produced an iconic Public Service Announcement that became commonly known as the “Crying

Indian” commercial. Mann remembers seeing it at age 6 or 7 when it first aired in 1971 on the second anniversary of Earth Day. “I grew up watching that commercial,” Mr. Mann said.

The commercial depicts a Native American silently paddling a canoe past factories spewing smoke and winding up on a shore full of litter and debris. Someone throws more trash at his feet from a passing car. The Native American faces the camera with a tear rolling down his cheek. A narrator’s voice intones:

Plastic pieces found in fecal matter of a sea turtle. PHOTO COURTESY OF FLORIDA GUMBO LIMBO NATURE CENTER INC.

“Some people have a deep, abiding respect for the natural beauty that was once this country. And some people don’t.”

“People start pollution. People can stop it.”

The Native American was actually an Italian American named Espera de Corti, the son of Italian immigrants. He became an actor and took the name “Iron Eyes Cody,” becoming famous portraying Native Americans in numerous films and advocating off-screen for Native American causes.

The ad was incredibly effective, Mr. Mann said.

When industry pushes off environmental responsibility on the consumer, “it’s traditionally known as ‘greenwashing,’” said Ms. Jones, the FGCU professor.

The tactic is familiar, said Ms. Warner, co-author of the Oceana study. “It’s clearly been shown over the years that a tactic the plastic industry uses is to tell us we need to recycle more, do it better. It’s the consumer’s fault for littering.”

A tiny sea turtle hatchling caught in a plastic tab. Scientists estimate that 15 million metric tons of plastic wash into the oceans every year. PHOTO COURTESY OF GUMBO LIMBO NATURE CENTER INC.

A 2018 article in Scientific American written by biologist Matt Wilkin puts things a little more bluntly.

“In fact, the greatest success of Keep America Beautiful has been to shift the onus of environmental responsibility onto the public while simultaneously becoming a trusted name in the environmental movement,” he wrote. “This psychological misdirect has built public support for a legal framework that punishes individual litterers with hefty fines or jail time, while imposing almost no responsibility on plastic manufacturers for the numerous environmental, economic and health hazards imposed by their products.”

Plastics producers

In 2021, the Minderoo Foundation of Australia published “The Plastic Waste Makers Index,” which identified the 100 companies that produce the five primary polymers that generate the vast majority of single-use plastic waste globally.

WHITEHEAD

The top three were ExxonMobil, Sinopec, which is a Chinese-owned company, and Dow.

Also in 2021, #breakfreefromplastic, another global movement, released its fourth annual global brand audit on the top plastic-polluting corporations of 2021. The audits were conducted by 11,184 volunteers in 45 countries. The top five are: The Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo, Unilever, Nestlé and Procter & Gamble.

Growing up, we were always taught that recycling is the answer. In the case of plastic waste, it isn’t. Or that is, it isn’t enough. Of course, you should always recycle all you can.

But the real problem is the lack of regulatory policy-making by our leaders and years of deflection by polluters more interested in bottom lines than keeping plastic bags off the bottom of the sea, scientists and environmentalists say.

ELKINS

There is a growing realization that we can’t recycle all this plastic waste. We lack enough recycling infrastructure or capacity to handle higher quantities that are being produced faster, as well as a growing variety of plastics. The cost of recycling is not economically profitable, while “virgin” plastic is readily available.

What can’t be recycled in existing plants and sold to a vendor may be put into landfills or burned. In 2018, the U.S. only recycled about 2% of its municipal plastic waste in its domestic facilities and burned six times that amount, according to the Plastic Pollution Coalition.

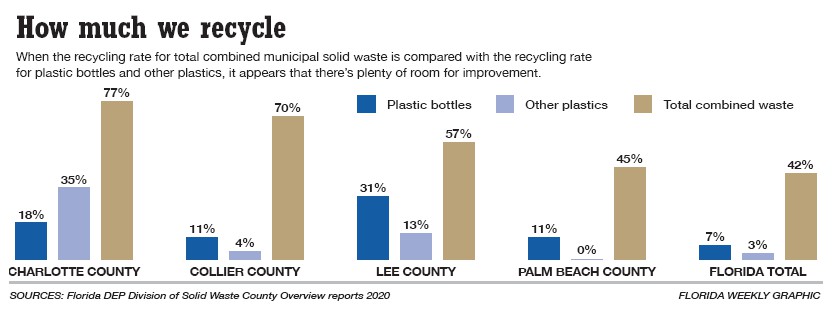

Nearly all Florida counties recycle, to varying degrees of success. In a sense, they’re doing the best with what they have.

“In our county, everything placed in recycling bins gets recycled,” said Brian Elkins, recycling business manager for the Solid Waste Authority of Palm Beach County.

Doug Whitehead, director of Lee County Solid Waste, said: “Lee County, with the help of private recyclers, has the means to recycle plastics in our waste stream. We are focused on proper reuse and recycling of the material and ending littering. When residents use our systems, the material is recycled.”

However, that doesn’t always happen. If the plastic in the recycling bin is contaminated (containing food or liquid residue) or has a type of plastic the county can’t handle, it won’t get recycled. The whole bin could be dumped out. Then the plastic could be landfilled or incinerated.

Plastic bags are also not recycled. They will get tangled in the recycling machinery and jam it up, Mr. Elkins said. Big Box stores, like Target, Publix, Walmart, will take the bags returned to their stores to their headquarters or warehouses, recycle and sell them on their own, he said.

Items that are recyclable will be taken to the county’s recycling facility, sorted in categories, crushed into bins, put on trailers and sold on the open market, Mr. Elkins said.

The “leftover” plastic, in both Palm Beach and Lee County, will be burned in their respective Waste-to-Energy facilities. This amounts to many thousand tons.

People try to make recycling an industry when recycling is not profitable, Ms. Jones said. If people get angry because they find out their curbside recycling is being burned or landfilled, that’s actually good, she said. It will cause them to speak up, get involved and push for more answers.

Policy lagging

The answer is making politicians set new policy to make manufacturers responsible, she said.

However, Florida has been a state “that does not respond to the need to control plastics,” Ms. Warner said.

Florida does not have a statewide law to regulate single-use plastic. But the state does have a preemption law that prohibits municipalities from banning or regulating plastic waste on their own. Florida is one of 19 states that has a pre-emption law when it comes to plastics. It’s known as “a ban on bans.”

Bills are proposed every year in the State Legislature to repeal these laws, but they never pass, including those proposed in 2022.The issue stems from a law that legislators passed in 2008 prohibiting local governments from passing plastic regulations in the state until the state DEP created recommendations and they were adopted by the Legislature, or the state rescinds the order. The law covered auxiliary containers, wrappings and disposable plastic bags. The state DEP did a retail plastic bags study in 2010 that looked at the problem and made recommendations. Nothing happened. The law laid dormant for 11 years.

In the interim, several municipalities tried to pass their own laws banning plastics, or some form of them. One example was the Town of Palm Beach in Palm Beach County, according to the study.

In June 2019 the council adopted an ordinance to prohibit the use of expanded polystyrene containers and single use carry out plastic bags within the city.

Weeks later the town received a letter from the Florida Retail Federation and Florida Restaurant & Lodging Association requesting the Town to repeal their ordinance, citing the ban. The town repealed their ordinance, then adopted a resolution to encourage the Legislature to approve any measure to repeal the preemption law.

In 2021 the Everglades Coalition sent a letter to Gov. Ron DeSantis, copied to legislative and state environmental officials, noting the impact of plastic pollution and asking for the law to be repealed.

Also In 2021, the legislature passed another bill calling for an update to the 2010 study to be completed and sent to the Legislature by Dec. 31, 2021. This was done.

The study, prepared by Timothy G. Townsend, lead investigator and University of Florida professor, and others, conducted five different surveys, one each for local governments, residents, retailers, manufacturers, and recycling facilities. The majority responded that regulation is needed. Among resident and local government stakeholders, 82% and 90%, respectively, of respondents reported a willingness to support additional waste reduction, reuse and recycling through increased fees

This is also the study that showed an estimated 7,000 tons of plastic waste went into Florida’s marine environment in 2020.

Plastic Free Florida, a movement to take action on plastics and foam locally and empower residents to achieve policy victories in their own communities through legislation, is watching this closely.

Lawmakers need to convert their thinking more in the direction residents want, Ms. Warner said.

There is a note of hope globally. On March 2, 175 nations at the United Nations Environment Assembly in Nairobi, Kenya signed an agreement to work on language for a global treaty that would tackle the proliferation of plastic waste and aim to regulate plastic production. The treaty language, which would be legally binding, is expected to be completed in 2024.

Federally, there is also a possibility for action.

The Break Free From Pollution Act was introduced in Congress in February 2020, according to the Surfrider Foundation, which helped lay the groundwork for the bill.

The bill was then reintroduced in March 2021. As of February, the 2022 version has 124 co-sponsors in the House of Representatives and 14 in the Senate.

A partial list of what the bill would accomplish:

¦ Require producers of packaging, containers and food-service products to design, manage and finance waste and recycling programs.

¦ Launch a nationwide beverage container refund program to bolster recycling rates.

¦ Ban certain single-use plastic products that are not recyclable.

¦ Ban single-use plastic carryout bags and place a fee on the distribution of the remaining carryout bags, which has proven successful at the state level.

“The U.S. produces more plastic waste than any other country,” Ms. Warner said. It makes much more sense to make less waste in the first place rather than turn off the tap as it gets into environment, she said. “I do hope for strong action at some point.” ¦

In the KNOW

HOW TO HELP

» Use reusable bags as much a possible when doing grocery or other shopping. Or ask for paper instead of plastic. For to-go items, ask for a paper box or a sheet of aluminum foil instead of a Styrofoam to-go container.

» Check what you can and cannot put in your recycling bin by contacting your city or county waste division/department. Make sure the items are clean and dry. Food or liquid residue is considered contamination and may result in those items or the whole bin having to be trashed instead of recycled.

» Not all plastic is accepted for recycling just because it’s plastic and/or has the chasing arrows logo (e.g. plastic straws and cutlery are not recyclable).

» Participate in local cleanups.

» Make your voice heard. Email, call or write a letter to your state representative and state senator asking them to repeal the plastic waste pre-emption law. To find them: www.myfloridahouse.gov/ www.flsenate.gov/senators/find

» Ask your city council and county commission to pass a resolution strongly encouraging the state legislature to repeal the pre-emption law.

» Email the governor at GovernorRon. Desantis@eog.myflorida.com

» Spread the word on social media.

From Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

» Report all entangled marine wildlife to the 24-hour FWC Wildlife Alert Hotline: 888- 404-3922.

» If you hook a bird, do not cut your line! Reel. Remove. Release. Do not discard monofilament fishing line. For more information, visit MyFWC.com/Unhook.

» Report Marine Debris Dumping U.S. Coast Guard National Response Center Hotline: 800-424-8802. To report marine debris in South Florida, call 1-866-770-7335.