It’s 6 p.m. and the pink-tinged skies turn black above Agolan, a village on the outskirts of Erbil in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq. Thick plumes of smoke have begun to billow out of dozens of flaring towers, part of an oil refinery owned by an Iraqi energy company called the KAR Group. The towers are just about 150 feet from where 60-year-old Kamila Rashid stands on the front porch of her house. She looks squarely at the oil plant, which sits on what she says used to be her family’s land.

Rashid was born here, like her parents before her and her children after her. She says when KAR moved into the area, residents traded their land for KAR’s promise of jobs and reliable, less expensive electricity for the village. The land was handed over, Rashid says, but she maintains that KAR never provided the promised electricity or long-term jobs.

The towers, also called flare stacks, are used by oil refineries across the globe to burn the byproducts of oil extraction. Such flaring releases a menagerie of hazardous pollutants into the air, including soot, also known as black carbon. “The smoke coats our skin and homes with black soot,” says Rashid. Many villagers keep their windows shut and try to remain indoors whenever possible.

Rashid’s neighbor, 29-year-old Bilah Tasim Mahmoud, joins her on the porch. The younger woman is holding a beat-up notebook with the names of women from Agolan who have miscarried. “No one is counting, but I am,” she says, flipping through the notebook’s pages. “We have had 300 miscarriages in this village since the oil field was developed,” she says, adding that she has been collecting this data but has no one official to take it to.

THE FIFTH CRIME: ECOCIDE

An ongoing series, produced in collaboration with Inside Climate News and NBC, about the campaign to make ecocide an international crime. See all stories in the series here. |

Miscarriages, of course, are common everywhere, and while pollution writ large is known to be deadly in the aggregate, linking specific health outcomes to local ambient pollution is a notoriously difficult task. Even so, few places on earth beg such questions as desperately as modern Iraq, a country devastated from the northern refineries of Kurdistan to the Mesopotamian marshes of the south — and nearly everywhere in between — by decades of war, poverty, and fossil fuel extraction.

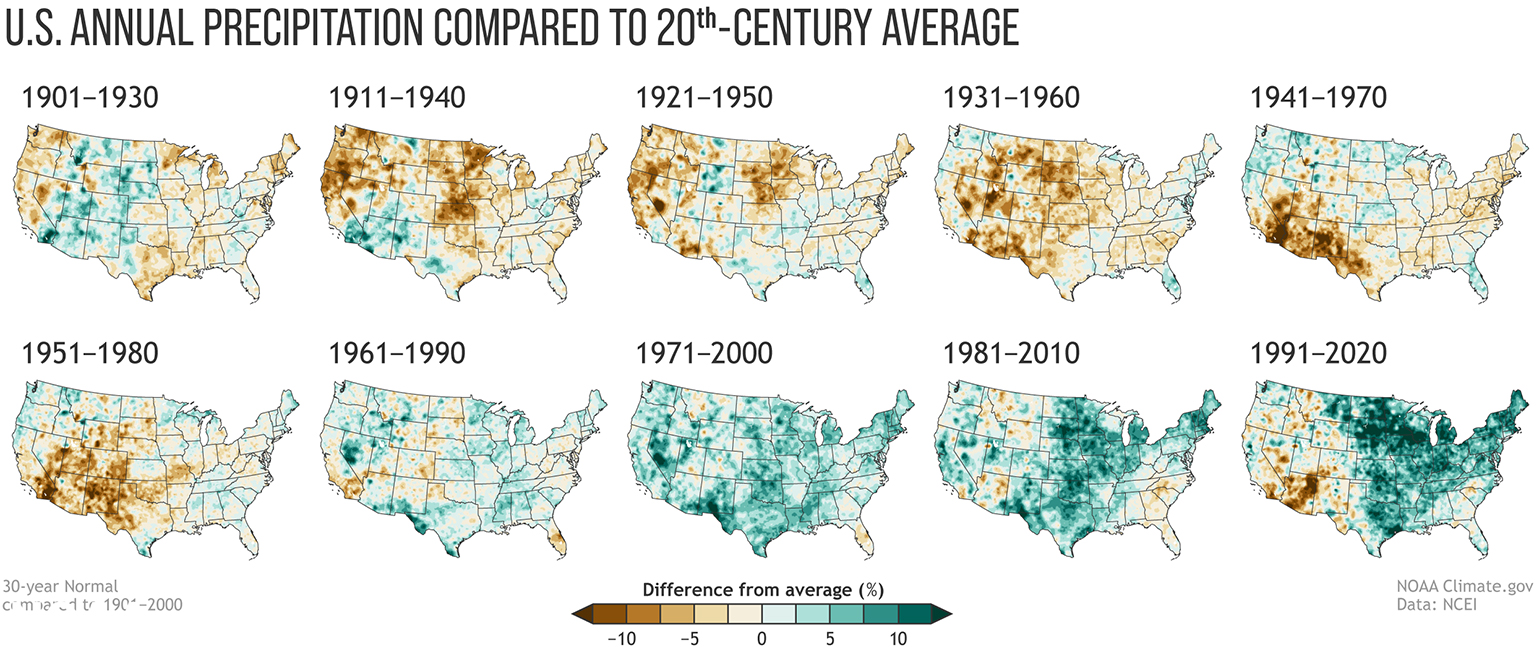

As far back as 2005, the United Nations had estimated that Iraq was already littered with several thousand contaminated sites. Five years later, an investigation by The Times, a London-based newspaper, suggested that the U.S. military had generated some 11 million pounds of toxic waste and abandoned it in Iraq. Today, it is easy to find soil and water polluted by depleted uranium, dioxin and other hazardous materials, and extractive industries like the KAR oil refinery often operate with minimal transparency. On top of all of this, Iraq is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change, which has already contributed to grinding water shortages and prolonged drought. In short, Iraq presents a uniquely dystopian tableau — one where human activity contaminates virtually every ecosystem, and where terms like “ecocide” have special currency.

According to Iraqi physicians, the many overlapping environmental insults could account for the country’s high rates of cancer, birth defects, and other diseases. Preliminary research by local scientists supports these claims, but the country lacks the money and technology needed to investigate on its own. To get a better handle on the scale and severity of the contamination, as well as any health impacts, they say, international teams will need to assist in comprehensive investigations. With the recent close of the ISIS caliphate, experts say, a window has opened.

While the Iraqi government has publicly recognized widespread pollution stemming from conflict and other sources, and implemented some remediation programs, few critics believe these measures will be adequate to address a variegated environmental and public health problem that is both geographically expansive and attributable to generations of decision-makers — both foreign and domestic — who have never truly been held to account. The Iraqi Ministry of Health and the Kurdistan Ministry of Health did not respond to repeated requests for comment on these issues.

Kamila Rashid and her family. The KAR refinery looms in the background. Due to pollution from the refinery, Rashid says, the family’s remaining land is no longer fit for agriculture.

The KAR Group refinery in Agolan village. Rashid says that when KAR moved into the area, residents traded their land for the promise of jobs and cheap electricity, which never materialized.

Children play in front of Bilah Tasim Mahmoud’s home. Mahmoud has been keeping track of the miscarriages that occur in Agolan, though she has no one official to take it to.

“Little priority has historically been given to the environmental dimensions of armed conflict, yet damage to the environment often echoes long into the future,” says Wim Zwijnenburg, who works for the Dutch peace organization PAX and has studied and written about the impact of war on the environment. He has investigated contamination in Iraq and says additional research is needed to clean up harmful toxins and mitigate health risks to people living in post-conflict regions.

The grim state of affairs is not lost on 27-year-old Idris Faroq, Rashid’s nephew, who works at the KAR refinery. (KAR also did not respond to multiple interview requests from Undark.) “If you travel to any village in Iraq, you will find contamination, radiation, and cancers,” he says. “This is the legacy of the American invasion and the wars that came before it — everyone left their waste behind.

“This land,” he added, “has been pillaged.”

Rashid’s family has grown wheat in Agolan for five generations, she says, but 15 years after the construction of the refinery, they are no longer able to support themselves as farmers. Rashid leaves her front porch to walk across the field that stands between her home and the facility. She says it’s the only land still owned by her family. “KAR uses the water from the river for their work and then they dump their waste,” she says, pointing at a pipe piercing through the exterior wall of the refinery. The waste flows directly into her family’s field, she says, and KAR also dumps its waste in the nearby river. The crops no longer grow, Rashid says, and anyway, the land “isn’t safe for agriculture now. And it isn’t safe for us.”

“This is the legacy of the American invasion and the wars that came before it — everyone left their waste behind,” Faroq said, adding: “This land has been pillaged.”

In Kurdistan, miles of pipelines shared with Turkish, Norwegian, and other international energy companies snake across the dry landscape, and the last decade has seen unregulated international, government, and militia oil refineries and oil fields pop up on contested lands, where drilling and flaring unfolds in close proximity to residential areas. Some facilities have been built within villages, expelling residents from their land and homes. People living near the refineries insist that they only started suffering from health ailments after the arrival of these companies and the pollution that came with them.

Rashid specifically mentions the fumes billowing from the flaring towers that surround her home, mindful that pollutants arising from flaring can increase myriad health risks for those living nearby. These towers were designed for the intentional burning of natural gas, a byproduct of pumping oil from the ground. While burning off the excess gas is technically better for the climate than merely venting it into the atmosphere, both have impacts on the climate — and more immediately on local health.

This past July, in an effort to address the issue, the Kurdistan Regional Government’s Ministry of Natural Resources issued a directive, giving oil companies 18 months to halt the flaring and instead seek ways to capture the gas and either reinject it underground, or use as an auxiliary power source. But this would mean additional costs for the companies, and it remains unclear whether the local industry has the technical and financial capacity to comply. And in any case, the government has little leverage to enforce the new policy — particularly given that the Iraqi economy is heavily dependent upon continued and robust oil exports, which account for more than 95 percent of state revenues.

As it stands, Iraq is the world’s sixth-largest oil producer. In 2020, the country ranked only behind Russia in the amount of gas flared, according to the World Bank, and air quality in the north — as with much of the country — can be relentlessly unhealthy to breathe.

Yasin Omar and his two children live in the village of Moqeble near the Kwashe landfill.

The impacts are not only airborne. Roughly 100 miles northwest of Agolan is the Kwashe landfill, a monster dumpsite surrounded by agricultural land and, workers estimate, dozens of oil companies. Used for both domestic and industrial waste, the landfill is leaking oil and industrial waste into the surrounding environment. And like the residents of Agolan, those living in villages near Kwashe say they are suffering from an array of health problems, including migraines, fatigue, skin conditions, miscarriages, cancer, and respiratory problems such as shortness of breath and asthma.

“In Iraq, we often say that every family includes someone with cancer,” says 43-year-old Yasin Omar, who lives less than a mile from the landfill in the village of Moqeble. Omar used to work at an oil company himself until health problems arose. “This village is almost 60 years old and was here long before the oil companies moved in. There used to only be 10 companies here and now there are more than 100,” he says.

According to Omar, many residents have decided to relocate. Some left because they found it so difficult to breathe the polluted air. Others left after developing cancer. Local residents are in an impossible situation, he says, given that the oil companies and a nearby PVC factory provide some of the only employment opportunities. And according to Omar, workers in both places are falling ill. This includes Omar, who says he was diagnosed with cancer last year. His two children, he says, also suffer from health problems.

Cancer has been linked to an overall decline in the health of Iraqis since the 1990s, though precisely what’s driving it is under dispute. In the past, officials from the Iraqi Ministry of Health have said that cancer numbers were rising in large part due to the use of depleted uranium munitions during the 1991 Gulf War by the United States and British militaries. Both countries have disputed those claims.

That’s the problem, experts who study Iraq’s complex mosaic of pollution and health challenges say. Despite overwhelming evidence of pollution and contamination from a variety of sources, it remains exceedingly difficult for Iraqi doctors and scientists to pinpoint the precise cause of any given person’s — or even any community’s — illness; depleted uranium, gas flaring, contaminated crops all might play a role in triggering disease.

Absent international assistance, they say, answers will continue to be elusive. “We don’t have the facilities or equipment,” says Bassim Hmood, a cancer specialist in Al Nasiriyah in southern Iraq, “to test the causes of the cancers.”

Roughly 250 miles south of Agolan, a pediatrician named Eman navigates the bustling, narrow corridors of Baghdad’s Central Pediatric Teaching Hospital. (Eman would only provide her last name to Undark and attempts to follow up with her were unsuccessful.) It’s an August morning and the waiting areas outside the wards are full. Eman stops for a moment to direct a patient to the proper room then pulls a pen from her white physician’s coat to sign a form for another. It’s technically her lunch break, but it’s busy on the ward today. She will work through lunch.

This is Eman’s sixth year at the hospital, and her 25th as a physician. Over that time span, she says, she has seen an array of congenital anomalies, most commonly cleft palates, but also spinal deformities, hydrocephaly, and tumors. At the same time, miscarriages and premature births have spiked among Iraqi women, she says, particularly in areas where heavy U.S. military operations occurred as part of the 1991 Gulf War and the 2003 to 2011 Iraq War.

Research supports many of these clinical observations. According to a 2010 paper published in the American Journal of Public Health, leukemia cases in children under 15 doubled from 1993 to 1999 at one hospital in southern Iraq, a region of the country that was particularly hard hit by war. According to other research, birth defects also surged there, from 37 in 1990 to 254 in 2001.

It remains exceedingly difficult for Iraqi doctors and scientists to pinpoint the precise cause of any given person’s — or even any community’s — illness.

But few studies have been conducted lately, and now, more than 20 years on, it’s difficult to know precisely which factors are contributing to Iraq’s ongoing medical problems. Eman says she suspects contaminated water, lack of proper nutrition, and poverty are all factors, but war also has a role. In particular, she points to depleted uranium, or DU, used by the U.S. and U.K. in the manufacture of tank armor, ammunition, and other military purposes during the Gulf War and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The United Nations Environment Program estimates that some 2,000 tons of depleted uranium may have been used in Iraq, and much of it has yet to be cleaned up. The remnants of DU ammunition are spread across 1,100 locations — “and that’s just from the 2003 invasion,” says Zwijnenburg, the Dutch war-and-environment analyst. “We are still missing all the information from the 1991 Gulf War that the U.S. said was not recorded and could not be shared.”

Souad Naji Al-Azzawi, an environmental engineer and a retired University of Baghdad professor, knows this problem well. In 1991, she was asked to review plans to reconstruct some of Baghdad’s water treatment plants, which had been destroyed at the start of the Gulf War, she says. A few years later, she led a team to measure the impact of radiation on soldiers and Iraqi civilians in the south of the country.

Around that same time, epidemiological studies found that from 1990 to 1997, cases of childhood leukemia increased 60 percent in the southern Iraqi town of Basra, which had been a focal point of the fighting. Over the same time span, the number of children born with severe birth defects tripled. Al-Azzawi’s work suggests that the illnesses are linked to depleted uranium. Other work supports this finding and suggests that depleted uranium is contributing to elevated rates of cancer and other health problems in adults, too.

Today, remnants of tanks and weapons line the main highway from Baghdad to Basra, where contaminated debris remains a part of residents’ everyday lives. In one family in Basra, Zwijnenburg noted, all members had some form of cancer, from leukemia to bone cancers.

Tanks were removed from this depleted uranium site along a main road in Basra, but remnants of weaponry pollute the soils and water.

To Al-Azzawi, the reasons for such anomalies seem plain. Much of the land in this area is contaminated with depleted uranium oxides and particles, she said. It is in the water, in the soil, in the vegetation. “The population of west Basra showed between 100 and 200 times the natural background radiation levels,” Al-Azzawi says.

Some remediation efforts have taken place. For example, says Al-Azzawi, two so-called tank graveyards in Basra were partially remediated in 2013 and 2014. But while hundreds of vehicles and pieces of artillery were removed, these graveyards remain a source of contamination. The depleted uranium has leached into the water and surrounding soils. And with each sandstorm — a common event — the radioactive particles are swept into neighborhoods and cities.

Cancers in Iraq catapulted from 40 cases among 100,000 people in 1991 to at least 1,600 by 2005.

In Fallujah, a central Iraqi city that has experienced heavy warfare, doctors have also reported a sharp rise in birth defects among the city’s children. According to a 2012 article in Al Jazeera, Samira Alani, a pediatrician at Fallujah General Hospital, estimated that 14 percent of babies born in the city had birth defects — more than twice the global average.

Alani says that while her research clearly shows a connection between contamination and congenital anomalies, she still faces challenges to painting a full picture of the affected areas, in part because data was lacking from Iraq’s birth registry. It’s a common refrain among doctors and researchers in Iraq, many of whom say they simply don’t have the resources and capacity to properly quantify the compounding impacts of war and unchecked industry on Iraq’s environment and its people. “So far, there are no studies. Not on a national scale,” says Eman, who has also struggled to conduct studies because there is no nationwide record of birth defects or cancers. “There are only personal and individual efforts.”

“Every U.S. base had a burn pit,” Salam Alzaidi says bluntly, taking a seat in a cafe on the outskirts of Baghdad. Between 2009 and 2010, he worked at bases across Iraq as a program manager for L3 Harris Technologies, an American aerospace and defense company.

During the Iraq War, U.S. military bases used burn pits as a way to dispose of an array of industrial, military, and medical waste, which was variously comprised of paint, plastics, used medical supplies, electronics, spent munitions, petroleum products, lubricants, rubber, and an array of other items, including human waste. The refuse was burned in open pits, sometimes along with unexploded ordnance — an ostensibly “controlled detonation.” According to reports, at just one base, Balad Air Base, the U.S. military burned an estimated 140 tons of waste a day in open air pits.

The burning of such material created clouds of black smoke made up of numerous pollutants, including particulate matter and dioxins like a chemical weapon called hexachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. “Even though these were controlled detonations, they would leave the whole area contaminated,” says Alzaidi. “These were huge detonations, and many bases are located near residential and agricultural areas.”

(The actual number of bases with burn pits is contested, but the U.S. military has only publicly identified around 40. In an email to Undark, Richard Kidd, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Defense for Environment and Energy Resilience, acknowledged that the military still had nine active burn pits at bases throughout the Middle East and Afghanistan, though he did not respond to other questions regarding contamination or Iraqi residents’ claims of health problems related to burn pits.)

Alzaidi says he worried about the health of residents living close to the bases. He recalls a time in 2006 — before he started working on the burn pits — when military waste was burned at a base in Anbar and the U.S. military used speakers to warn locals not to drink the water in their village for a week. “They just said, ‘do not drink this water,’ but did not explain why,” says Alzaidi. He says that most of the locals didn’t understand what was said through the speakers, and those who did were uncertain about how, exactly, the water was contaminated. Many drank the water anyway.

After the Gulf War, many veterans suffered from a condition now known as Gulf War syndrome. Though the causes of the illness are to this day still subject to widespread speculation, possible causes include exposure to depleted uranium, chemical weapons, and smoke from burning oil wells. More than 200,000 veterans who served in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere in the Middle East have reported major health issues to the Department of Veterans Affairs, which they believe are connected to burn pit exposure. Last month, the White House announced new actions to make it easier for such veterans to access care.

Numerous studies have shown that the pollution stemming from these burn pits has caused severe health complications for American veterans. Active duty personnel have reported respiratory difficulties, headaches, and rare cancers allegedly derived from the burn pits in Iraq and locals living nearby also claim similar health ailments, which they believe stem from pollutants emitted by the burn pits.

Keith Baverstock, head of the Radiation Protection Program at the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Europe from 1991 to 2003, says the health of Iraqi residents is likely also at risk from proximity to the burn pits. “If surplus DU has been burned in open pits, there is a clear health risk” to people living within a couple of miles, he says.

Abdul Wahab Hamed lives near the former U.S. Falcon base in Baghdad. His nephew, he says, was born with severe birth defects. The boy cannot walk or talk, and he is smaller than other children his age. Hamed says his family took the boy to two separate hospitals and after extensive work-ups, both facilities blamed the same culprit: the burn pits. Residents living near Camp Taji, just north of Baghdad also report children born with spinal disfigurements and other congenital anomalies, but they say that their requests for investigation have yielded no results.

More than a dozen rivers snake through Iraq, tributaries of the mighty Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which flow into the Mesopotamian Marshes, also known as the Iraqi Marshes, a wetland area located in the southern part of the country. Once, the marshes were a literal oasis in the desert, but now they are a thirsty expanse. Sun scorched grasslands lead the way to what is left of the dried-out marshes. These marshes are not only wracked by evaporation, they are also badly polluted with the black wastewater carried in from sewage pipes that connect back with the region’s heavy industry.

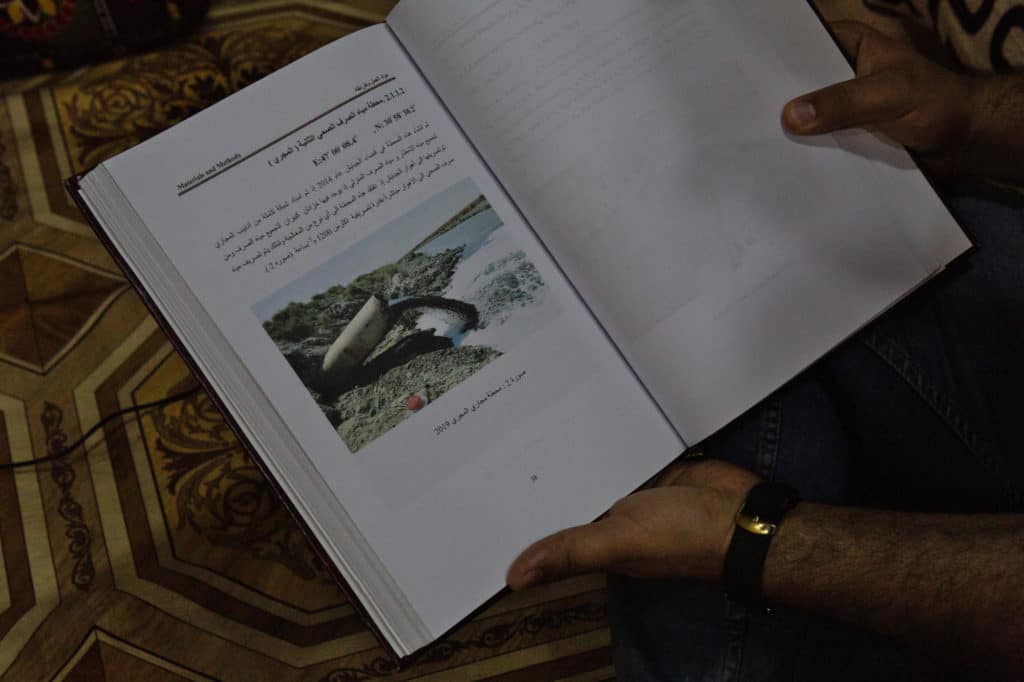

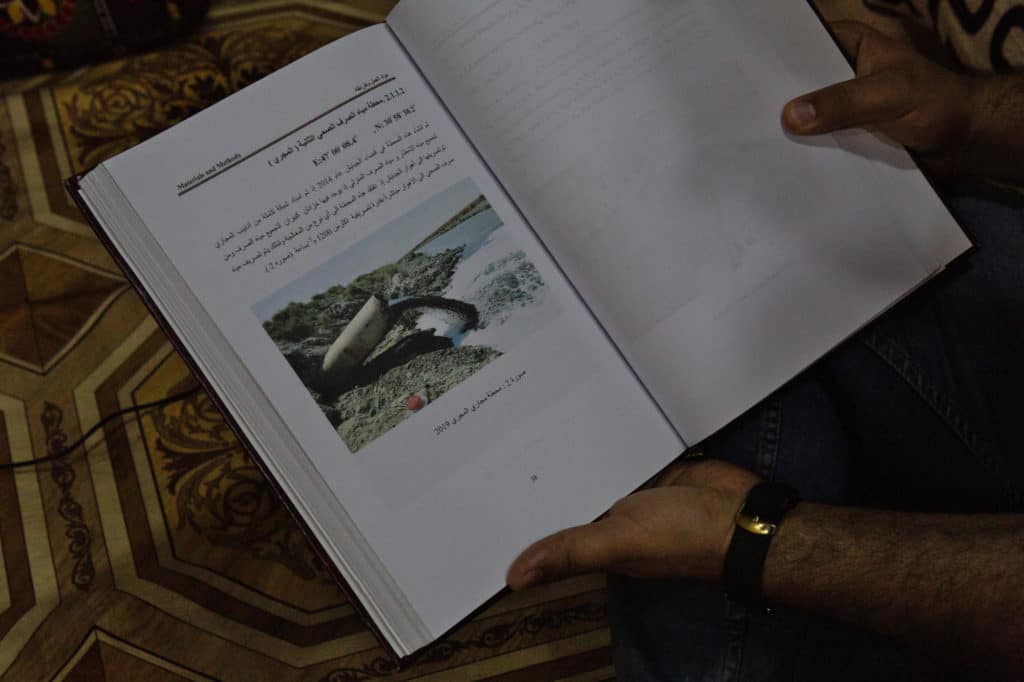

Azhar Al-Asadi, a 31-year-old member of Save the Tigris organization and a water environmentalist, stands outside his home nestled on the corner of a quiet street. In the crook of his arm is his masters thesis on pollution in the nearby marshes. He keeps his hands stuffed inside his pockets, only removing them briefly to wipe sweat from his brow. It is a stifling 123 degrees Fahrenheit, and there’s not a whip of wind to offer any respite.

“The land here is starved of water,” says Al-Asadi. “The little water we have is heavily polluted and contaminated. Everything living is dying — plants, animals, and humans. There needs to be a concrete plan for sustaining everyday life on this land. Iraq needs to work towards environmental sustainability,” he says. “But these marshes are being abandoned. They are a dumping ground.”

Abdul Wahab Hamed, who lives near the former U.S. Falcon Base, says his nephew was born with severe birth defects. According to local hospitals, the likely cause is the burn pits.

Environmentalist Azhar Al-Asadi has studied the pollution in marshes near Al-Chibayish. He says the marshes are a dumping ground and advocates for Iraq to make a sustainability plan.

Al-Asadi, like his father before him, was born and has spent his entire life in the town of Al-Chibayish in Dhi Qar Governorate, in southern Iraq, where the family once enjoyed fishing the meandering waterways. “I love this region,” he says, now standing beside his boat and looking out across the marshes that stretch to the horizon in every direction. The water is undisturbed, barely rocking Al-Asadi’s boat. The tall marsh grass lining the narrow waterways barely quivers in the still heat.

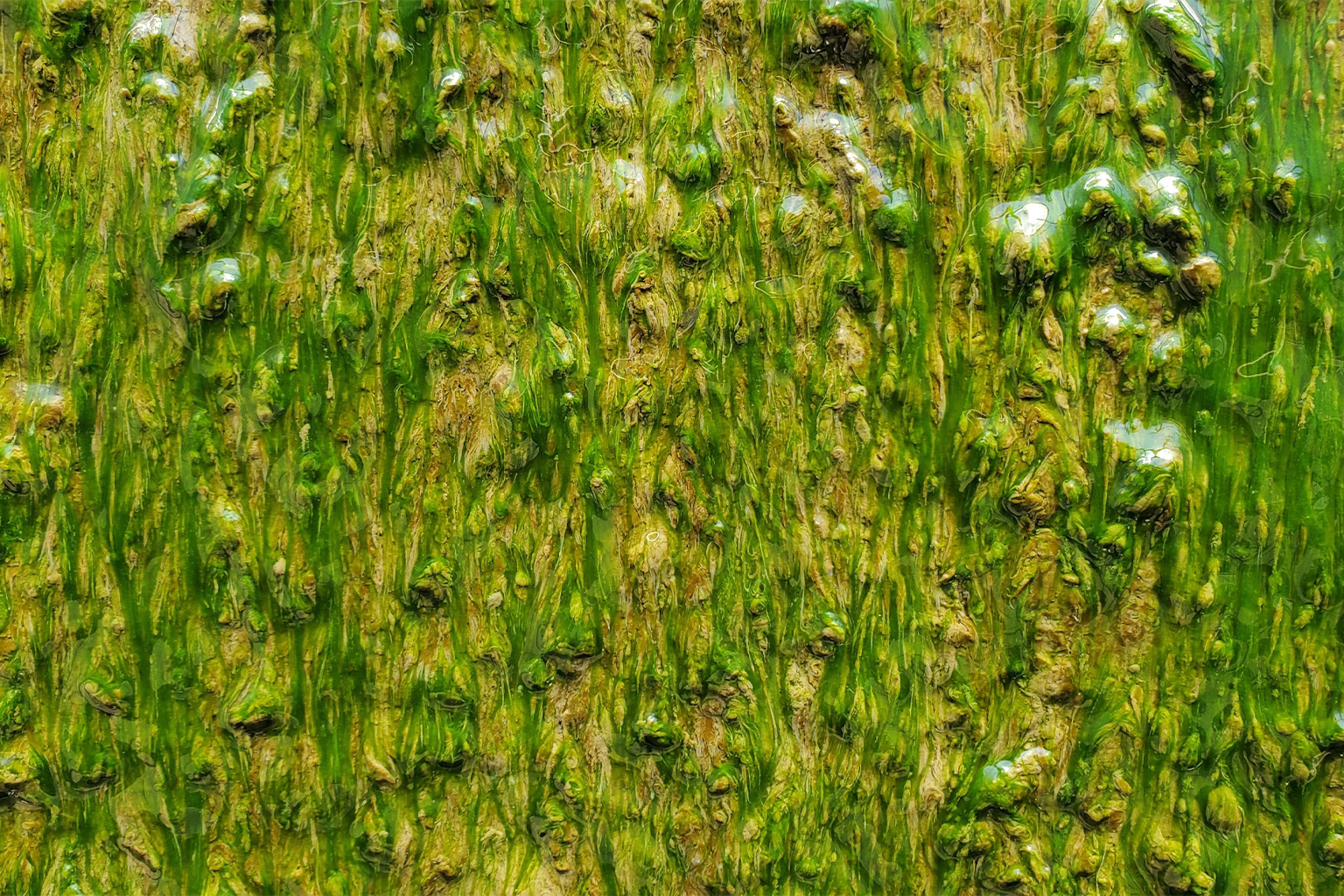

“I remember fishing here with my father as a young boy, but look at it now: the fish are already dead, floating on top of the water,” he says, pointing out a pile of fish floating in stagnant green water near a sewage point. It’s a familiar complaint in and around the marshes. Iraq’s environmental crisis bears heavily on the Euphrates and the Tigris, which provide nearly all the water to the country. Contamination in both waterways and their many tributaries is rife — byproducts of decades of both inadvertent and deliberate destruction.

During the war with Iran, which spanned the 1980s, former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein accused the region’s Indigenous inhabitants, known collectively as Marsh Arabs, of treachery. He dammed and drained Iraq’s iconic marshes to flush out rebels hiding in the reeds. By 2001, the wetlands were less than 7 percent of their size, according to estimates in a United Nations Environment Program report. Though the marshes had been partially restored since then, they are now dwindling once again.

Then, at the start of the Iraq War, the Tuwaitha Nuclear Research Center — known colloquially as the “yellowcake factory” — was looted. Barrels of radioactive waste were emptied in and around the facility just outside Baghdad. Some of the barrels containing uranium were stolen and dumped in rivers and barrels were found and used by people in the surrounding villages to preserve water and food, not knowing they were contaminated, says Al-Azzawi. Local residents were additionally exposed via contaminated dust.

“Everything living is dying — plants, animals, and humans. There needs to be a concrete plan for sustaining everyday life on this land,” says Al-Asadi.

Now Iraq’s waterways face a new threat. Seventy percent of Iraq’s industrial waste is being dumped directly into rivers or the sea, according to researchers. Harry Istepanian, senior fellow at the Iraq Energy Institute, says that the rivers and crisscrossed canals leading off the marshes in southern Iraq are highly contaminated with industry waste, sewage, pesticides, sunken ships, and other military debris that have sat at the bottom of the waterways since the 1980s.

Ships seemingly covered in rust can be seen half submerged in water around the marshes, he says. Many of them “still hold oil products, unexploded ordnance, and possibly rocket fuel, propellants, and toxic chemicals” and may still be leaking, he wrote in an email to Undark. “There are still more than 260 sunken ships — including tankers, tugs, barges, and patrol boats,” he continued, which clog the waters and, if dredged, might cause additional water pollution.

A 2019 U.N. Environment Program report noted that old and poorly maintained oil pipelines across the country were leading to spillages that were having a significant impact on the health of Iraqi communities as well as natural ecosystems. Istepanian says several of these spillages were near the Basra Shuaiba refinery’s wastewater infrastructure. A 2016 study published in the Engineering and Technology Journal analyzed dozens of water samples over a six month period. The authors found extreme levels of water pollution in the vicinity of the refinery and downstream of the Shatt Al-Basra river into which the refinery’s wastewater is dumped. In 2019, Human Rights Watch warned that the high salinity of Shatt Al-Arab river in Basra will cause serious environmental and health problems.

“Shatt-al-Arab and its canals,” Istepanian says, are “a stream of toxic waste.” There is fear that the 2018 water crisis might happen again. That summer, at least 118,000 people were hospitalized due to symptoms doctors identified as related to water quality, he says. And the soil contamination and air pollution from expanding oil fields and gas flaring are infiltrating area aquifers. “The polluted groundwater is now becoming extremely difficult and costly to make it safe, and it may be unusable for decades,” he adds.

Al-Asadi studied two of six sewage points in Al-Chibayish for his 2019 masters thesis. He collected samples in 2018 and 2019 and worked to identify the degree of pollution they are producing. “One sewage station alone will reach 1,200 square meters of the marshes per hour,” he says. “My study clearly showed that these sewage stations produce pollution which is harmful to human beings, animals, and plants.”

The Mesopotamian Marshes, also known as the Iraqi Marshes, are a wetland area located in the southern part of the country.

The marshes are polluted with wastewater from the region’s industry, often dumped directly into waterways by sewage pipes.

In the 1980s, to flush out rebels hiding in the marshes, then-President Saddam Hussein had them dammed and drained. As a result, the wetlands dwindled to less than 7 percent of their size.

The light from an oil company’s flaring reflects on polluted waters near Basra. Some canals in the region have been described as “a stream of toxic waste.”

Al-Asadi shows a photo of pollution draining into the marshes, which he studied for his masters thesis. He has found the waterways contain high levels of harmful toxins such as phosphorus, ammonium, and nitrate.

There is no upstream filtration system, Al-Asadi says, which means waste from hospitals, industry, and more “is going straight into the marshes.” Throughout his research, he has collected samples from the waterways in Chibayish and found the water to contain high levels of harmful toxins such as phosphorus, ammonium, and nitrate. “The water belongs to everyone, and yet it is not safe for anyone,” he says. His findings, which published in 2020, match up with previous work in the area. For instance, in 2011, a team of Iraqi scientists reported the same pollutants in the waterways in the Journal of Environmental Protection. Other research has found heavy metals and hydrocarbons in the marshes, and confirmed the high levels of salinity.

Al-Asadi says he can measure the radiation and pollution in the marshes, but Iraq only has basic equipment for testing and so the samples must be sent outside of the country, a lengthy and expensive process. But despite the challenges, he says, he will continue his research to raise public awareness about the pollution.

“The government, civil society organizations, and the public are doing nothing to prevent the pollution or find alternatives,” says Al-Asadi.

“I showed my findings to Iraqi government officials but they just ignored my studies. They are responsible to prevent more pollution or at least transfer these companies to remote areas. If they don’t, the conditions will deteriorate further and then we will be at the point where we can no longer amend the situation.”

Seventy percent of Iraq’s industrial waste is being dumped directly into rivers or the sea, according to researchers.

In 2020, the U.N. Environment Program announced initiatives to address the steep environmental challenges in Iraq. That September, for instance, the organization announced a partnership with the Iraqi government to spend $2.5 million to help the country adapt to climate change. One month later, the U.N. Environment Program and the U.N. Development Program in Iraq signed an agreement to accelerate their environmental goals, which the organizations aim to hit by 2030, including addressing pollution and waste management.

In a press release, Zena Ali Ahmad, resident representative of the U.N. Development Program in Iraq, said: “Iraq faces a number of environmental challenges — from water scarcity, to rising temperatures, to pollution, to environmental degradation due to years of conflict and neglect. Tackling these challenges in a complex setting like Iraq cannot be done alone.” (The U.N. Environment Program did not respond to multiple interview requests.)

Meanwhile, the toll of the country’s longstanding environmental devastation continues.

Back in Agolan village in Kurdistan, the KAR Group has begun flaring again. To Idris Faroq, Rashid’s nephew, it’s just another insult in a land scarred by generations of combat and unchecked greed – both foreign and domestic. “Meanwhile,” he says, “there is nothing left for us.”

Rashid suggests there is one thing left behind: illness. Standing in the former wheat field near her home, she gazes at the raging flames towering several stories above her. She has to shout to be heard above rumbling noise of the flaring gas.

“Everyone here is sick,” she says. “When I’m trying to breathe, it’s like I’m dying.”

Lynzy Billing is a freelance writer and photographer based in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The Fifth Crime is an ongoing series, produced in collaboration with Inside Climate News and NBC, about the campaign to make “ecocide” an international crime. See other installments here.