On a warm windy day in early April, Jace Tunnell steps out of his car at Morgan’s Point, a spit of land that juts out into the Houston Ship Channel in Texas. Tunnell, a marine biologist and reserve director at the University of Texas Marine Science Institute, sets his watch and gets to work, walking along the high-tide line and picking up every plastic pellet he can see.

The tiny pellets, known as nurdles, are the starting point in the creation of vast amounts of plastic products, and those, in turn, are part of a web of plastics that encircles the globe. Tunnell steps and bends, filling his palm, as he has done on beaches across the country. Each pellet is a data point about plastics. It’s joined by others collected as university students dip nets into the waters of the North Atlantic, satellite instruments measure light reflecting off plastic debris afloat on the ocean, and scientists drop GPS-tagged bottles into India’s Ganges River.

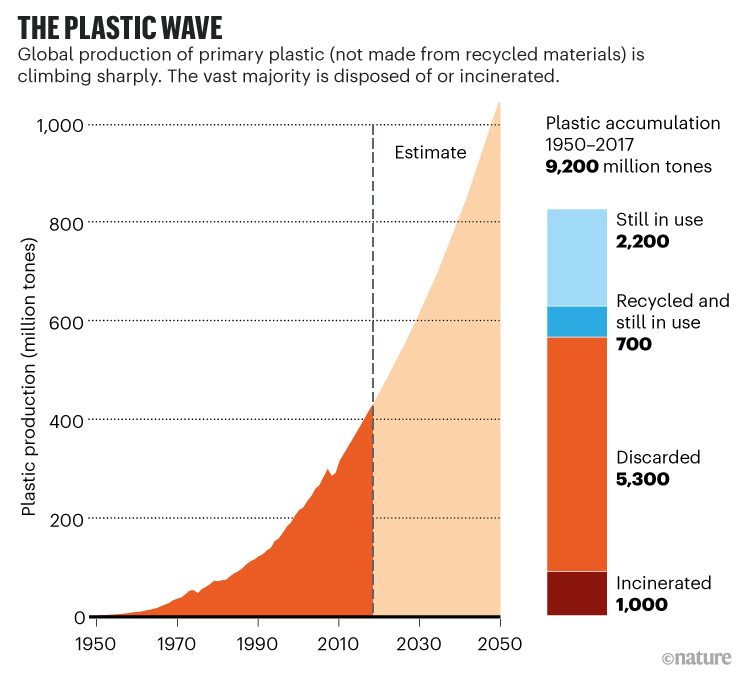

Together, all these researchers are helping to illuminate a complex and growing plastics-pollution problem that is transforming life across the planet. Of the 9.2 billion tonnes of non-recycled plastics produced between 1950 and 2017, more than half was made in this millennium and less than one-third is still in use1 (see ‘The plastic wave’). Of the waste, nearly 80% has been buried in landfill or found its way into the environment, and a scant 8% recycled1. By 2060, plastic waste could triple from 2019 levels, and carbon emissions from the full life cycle of plastics are expected to more than double, according to a report this year2 from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Paris. By mid-century, nearly half of the growth in demand for oil could be driven by plastics. Around the world, people and countries are saying: enough.

Sources: Ref. 1

In March, after nearly 30 years of researchers warning that plastics were a growing global problem, 175 nations voted in Nairobi to create a legally binding international plastics treaty. Negotiations start in earnest in Uruguay on 28 November.

United Nations secretary-general António Guterres has proclaimed it “the most important deal since the Paris Agreement”. The Nairobi resolution calls for full-life-cycle assessments, from fossil-fuel well heads — where 99% of the raw materials for plastics originate — to final disposal. The resolution also requires action plans at national, regional and international levels that work towards preventing, reducing and eliminating plastic pollution.

Yet the only way to ensure that a treaty — expected to be completed by the end of 2024 — is effective is to know where plastics come from, where they go and who’s responsible, every step of the way.

“If we don’t have a baseline,” says Kara Lavender Law, an oceanographer at the Sea Education Association (SEA) in Falmouth, Massachusetts — an organization that has been monitoring ocean plastic since 1986 — “then we’ve got no measuring stick for progress.”

Research surge

Research on plastics pollution has exploded in the past decade, part of a growing body of studies revealing the biological, ecological and human-health consequences of synthetic polymer products that were nearly non-existent a century ago. There has been a slew of reports just in the past few years addressing different aspects of the pollution problem, including ones from the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)3 and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP)4. These reports echo the language of the Nairobi resolution in calling for a better understanding of the life cycle of plastics. “The idea is to capture the full scope of impacts from plastic,” says David Azoulay, director of environmental health and managing attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) in Geneva, Switzerland, which has produced multiple reports on plastics.

The NASEM report, released earlier this year, argues that the United States should establish a strategy by the end of 2022 for reducing plastic waste in the ocean, focusing on six stages of the problem, from production and product design to waste management. It also identifies knowledge gaps at each step and recommends moving to a circular economy — in which materials such as plastics are reused rather than thrown away. “How could we define avoidable, unnecessary and problematic plastics to start pushing them towards elimination?” asks Margaret Spring, chief conservation and science officer at Monterey Bay Aquarium in California and chair of the committee behind the report.

Landmark treaty on plastic pollution must put scientific evidence front and centre

That will demand unprecedented collaborations between scientists, citizens, policymakers and chief executives, because government and corporate data about the production and movement of plastics are riddled with gaps. Given that, researchers will play an especially important part in helping to collect the baseline data necessary to make the goals of a global plastics treaty meaningful and measurable.

“You can’t manage the thing you can’t measure,” said Law.

Nurdle hunt

Ten minutes into his plastics hunt, Tunnell stops collecting and counts his bounty: 98 nurdles, cupped against the wind in the palm of his hand. “Houston has 55 production facilities,” Tunnell says. “We know almost all are losing pellets.”

Today’s haul is an average one for these Gulf of Mexico beaches, although there was a 10-minute survey that yielded 328,000 pellets, after a container of nurdles spilled into the Mississippi River earlier this year. In Sri Lanka last year, a cargo ship carrying an estimated 75 billion nurdles sank offshore, coating beaches with thick layers of the plastic pellets, according to local reports and UNEP.

Tunnell will enter the data into the citizen-science app he created, called Nurdle Patrol. So far, more than 6,000 volunteers in 19 countries have pulled 1.8 million nurdles out of the environment and made note in the app. Nurdle Patrol data have aided in succesful lawsuits against companies in Texas and South Carolina over releases of plastic pellets into the environment.

Along with Nurdle Patrol, many other efforts are working to get a grip on the extent of plastic pollution. The UNEP report recognized 15 major monitoring programmes that focus on marine litter, and many of these crowdsource citizen-science data for researchers.

There is the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Debris Monitoring and Assessment Project, which partners with organizations to monitor shorelines in nine countries and uses the Marine Debris Tracker app. Another, Ocean Conservancy’s International Coastal Cleanup, started as a local campaign in Texas in 1986 and has grown to include 152 countries and 9 million volunteers, who can now enter data through the Clean Swell app for researchers to use. But even with all of these efforts, there is still no baseline for data. Researchers say that these citizen-science endeavours are positive steps but are limited in capturing the full scope of how much plastic is out there.

“If you look at the data from citizen science,” says Alexander Turra, an oceanographer at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, “they are all concentrated in the north, not in the south.” They also tend to be located in easy-to-reach places.

Even where data are available, arriving at a baseline remains a challenge on two fronts: standardizing methodologies for collecting data and agreeing on a place to share them. Recognizing the challenges of a single global (or even national) database, the NASEM report calls for tracking and monitoring systems that are scientific, adaptable and complementary.

Members of the Sri Lankan military clean up thick layers of plastic nurdles that washed up on beaches after a container ship sank offshore in May 2021.Credit: Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP via Getty

To deal with the disparities, the UN and other organizations have created guidelines for data collection, which has “contributed significantly to promote method harmonization”, says Daoji Li, director of the Plastic Marine Debris Research Center at East China Normal University in Shanghai, and a reviewer of the UN guidelines.

Li’s university established a centre to train scientists from across Asia in sampling techniques and measurements, he says, in the hope of bringing congruity to data across the region, including data from countries now receiving the bulk of the world’s plastic waste. Despite the big data gaps and lack of consistent methodologies, some researchers say there’s enough information to start identifying plastic pollution hotspots. “That is often a common trope, that we don’t have standard methods, so the data’s no good,” says marine ecologist Chelsea Rochman at the University of Toronto in Canada, who was one of the first to push for a global plastics agreement.

“Even if the emissions inventory isn’t perfect, if you’re using a harmonized protocol, you should at least be able to detect a difference,” she says of the plastics data. And with that ability, it’s possible to identify upward and downward trends and who the leaders and laggers are, crucial for enforcing a global treaty.

Lack of transparency

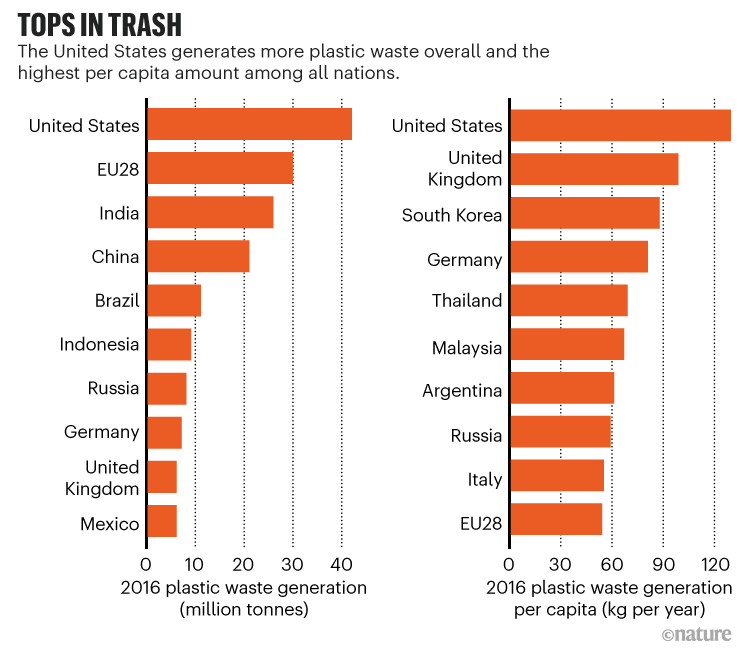

Reaching upstream in the plastics production line presents a different challenge for researchers. The lack of transparent data on production was one of the key knowledge gaps identified in the NASEM report, which focused on the US role in global ocean plastic waste. The attention on the United States is warranted; it generates more plastic waste than any other nation and even beats the entire European Union (see ‘Tops in trash’).

Source: Ref. 3

Despite the proprietary nature of company data, some researchers have tried to assess what enters the waste stream. Jenna Jambeck, an environmental engineer at the University of Georgia in Athens, published a landmark study in 2015, estimating that 8 million tonnes of plastic enter the world’s oceans every year5. But she recognizes the study’s limitations, partly because of this lack of transparency. Both she and Spring lament the inability, for example, to pin down data on polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the ubiquitous plastic used for soft-drink bottles and other common items.

Researchers worry that public discussions focus on recycling and ways to deal with the plastic once it has reached the consumer — ideas promoted by industry — rather than who is creating all the plastic and where it’s going. Hence the emphasis in the NASEM report and global talks on circular-economy design strategies that address that first stage in the plastic life cycle, production.

“We care so much about this material in the environment — that’s when we’re getting outraged,” Jambeck says. “But we don’t care about it before that point. If you want to prevent it from getting in the environment, we have to care so much more about it upstream, and track that data.”

Once plastic enters the waste stream, researchers rely heavily on the UN Comtrade database, which tracks publicly available plastic-waste data, to monitor where it goes and measure it over time and space. Yet Comtrade data neglect to track the ultimate environmental fate of plastics, and the data are only as strong as the official government trade and customs information from which they are derived.

A bulldozer moves plastic and other rubbish in 2021 at a waste facility in San Francisco, California.Credit: Justin Sullivan/Getty

“There are a lot of invisible plastics,” says Azoulay, with many gaps and inconsistencies in the data. Australia, for example, banned the export of plastic waste but still allows the export of compacted waste bound for cement kilns in Asia, which is classified as refuse-derived fuel. “That doesn’t show up as plastic in Comtrade data,” Azoulay says. Nor does plastic packaging, which accounts for 42% of non-fibre plastic resin.

In 2018, a seismic shift jolted the plastics industry: China implemented its National Sword programme, banning the import of most plastic waste. The country had taken in 45% of the world’s plastic waste since 1992. Then it shut its doors. Overnight, it reorganized the global movement of plastics, shifting final destinations for waste to Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia and India. Unexpected events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war further complicated plastic production and movement. And as new countries get inundated with plastic waste that they don’t have the facilities to handle, they often implement bans, but enforcement remains questionable.

Given this void, organized crime increasingly controls the trade in illegal plastic waste, according to the global police agency INTERPOL, making data even more difficult to capture. Plastics are misdeclared, concealed or shipped by circuitous routes to evade detection, amassing a carbon footprint that goes far beyond that from the plastics’ original utility, which is already hefty.

In an attempt to stem the tide, in 2019, the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Waste and their Disposal approved an amendment that categorizes plastics as hazardous waste, subject to tracking and reporting. A weakness of the convention is that the United States, with its enormous amounts of plastic waste, is not a signatory. Inside the country’s borders, the US Environmental Protection Agency classifies plastic as municipal solid waste, not a hazardous substance, so minimal tracking is required. But there is pressure to reclassify plastics as toxic, following the lead of the Basel Convention and countries such as Canada, which made the change last year. Likewise, plastic construction waste is left out of the accounting.

With all these missing pieces, sometimes it’s on-the-ground activists who fill data gaps. Like the one who discovered that what should have been a shipment of paper arriving in a port in East Java, Indonesia, was permeated with plastics. This was just one of many examples cited at a press event in June, when the non-profit Basel Action Network (BAN), a plastics and toxic materials watchdog group based in Seattle, Washington, presented a dismal first-year report card on the Basel amendment. BAN founder and executive director Jim Puckett reported that countries were refusing to implement or enforce the new rules. The violations, he said, “threaten the integrity of the agreement”.

The mislabelled shipment to Indonesia was just a hint of the plastic deluge hitting the country; the amount of plastic waste Indonesia imports more than doubled in 2021 compared with 2020. Southeast Asia is just one of many regions being inundated with plastic waste, and this is exacerbating global inequalities in pollution. It extends to all stages of the plastics life cycle, from oil-and-gas extraction to the siting of plastic production facilities to the management of waste. “There is a plastics tsunami already happening on the ground” in Africa, says Leslie Adogame, executive director of Sustainable Research and Action for Environmental Development Nigeria, a think tank in Lagos.

How to globalize the circular economy

Countries taking in plastic waste are often not where the plastic was produced or used. And many countries at the tail end of the plastics life cycle lack the capacity to train customs inspectors or build state-of-the-art recycling facilities. This “makes Africa a dumping ground”, Adogame says, and similar stories are emerging from southeast Asia and Latin America, in what has been described as ‘waste colonialism’. All of this exacerbates the unknowns about where plastics are ending up.

These limitations are playing out in the data collection as well. Turra says that Brazil’s ocean-monitoring resources are a tiny fraction of what the United States devotes. But, rather than trying to measure everything, he advocates training people who are already in the field to gather simplified data. Is a beach very clean, very dirty or somewhere in between? That level of detail is enough, he says.

Tracking data

Others agree that, given the mounting plastic pollution crisis and the continuing struggle to fill data gaps, it is essential to focus attention on a few key areas. “It’s an absolute necessity to prioritize,” Spring says. “To do that, you’ve got to identify the biggest source hotspots.”

At the same time, developments in technology are opening up avenues for collecting data. One method that shows promise is putting GPS trackers in plastic-waste shipping containers, says Puckett. “That really follows the waste all the way,” he says. “That’s the future.” Such tracking can help to monitor plastic-waste violations, and improve researchers’ knowledge of how plastics move globally.

The urine revolution: how recycling pee could help to save the world

An international team led by women, and partially funded by the National Geographic Society, fitted satellite tag devices into 500-millilitre PET bottles and dropped them into the Ganges River. The project is studying 40 sites along the river, ranging from rural to urban, both before and after the monsoon rains. Sampling revealed that three-quarters of the waste flushed downstream by the rains was plastic6. The team and other researchers dropped tagged bottles in the Ganges delta, and watched one travel more than 2,800 kilometres over the course of 3 months, swirling along the Indian coastline7. In the open ocean, GPS devices are helping to track the estimated 50 million kilograms of plastic fishing gear that is abandoned, lost or dumped annually, and also often left out of plastic-pollution accounting.

Tracking data are also coming from sensors on satellites, aircraft, drones and ships. Researchers are using the European Union’s Copernicus Sentinel-2 pair of satellites, for example, to identify slicks of marine litter that accumulate on the ocean’s surface. Satellite imagery and machine learning are still in the early stages of being calibrated by human observation on ocean expeditions.

Researchers hope that the momentum building around the global plastics treaty will help to unify the disparate bits of information into a coherent image that guides policy in a meaningful way. They also hope that policies will be adaptable so that they improve with better plastics knowledge.

“We know what a lot of this stuff is, and governments need to prioritize it and industry needs to be willing to adapt,” says Rochman. “Watching where climate change is, and all of the data that’s coming out, and the actual disasters we’re seeing around the world that are the consequences of us not moving fast enough,” she says, “I don’t want us to do that with plastic.”