A toxic train derailment in Ohio has forced an uncomfortable conversation in the US. The pollution and response to the accident was bad enough for local residents, but black and lower-income communities face the effects of America’s dirty plastic industry on a daily basis.

Dramatic images of the Ohio train derailment and its aftermath gripped the world’s attention in February: a huge plume of thick, black smoke towering into the atmosphere; the blackened carcasses of railcars on their sides, scattered in an unnatural formation; a land scorched and scarred from 50 rail cars, many carrying toxic chemicals, coming off the tracks.

Scientists have told E&T that it could be decades before long-term health impacts of the accident are fully understood. They are concerned about the release of carcinogenic chemicals into the atmosphere, as well as into the soil and potentially, the food chain.

However, the Ohio derailment was more than a one-off environmental disaster. The accident has lifted the lid on policies around hazardous chemicals, as well as corporate responsibility and environmental injustice.

Mike Schade, an expert from the group Toxic-Free Future, has been warning about the whole lifecycle dangers of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic, for years. “PVC releases highly hazardous chemicals, and it has had devastating impacts for communities and workers for decades. We call it the poison plastic,” he says.

The Ohio train derailment saw 38 cars derailed, including 11 containing hazardous materials, forcing hundreds of local residents to evacuate for several days Image credit: Gettyimages

Many vinyl chloride and PVC production facilities in the US are in Texas, Kentucky and along an 85-mile stretch of the Mississippi River in Louisiana, where local residents are predominantly black and low-income. Rates of cancer in the area are so much higher than the rest of the country that this corridor is now known as ‘Cancer Alley.’

“Communities of colour and low-income communities face pollution as well as serious risks associated with accidents and explosions day in and day out in places like Cancer Alley. Sadly, they don’t get quite the attention this derailment has gotten,” says Schade.

The accident has also brought issues surrounding rail safety into sharp focus. On average, there were three train derailments a day in the US last year – E&T has previously revealed concerns that profits were being prioritised over safety in the rail sector. However, for Judith Enck, president of campaign group Beyond Plastics and former regional administrator at US environment regulator the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), says there is still not enough focus on “why we are transporting toxic vinyl chloride all over the country on a rickety rail system” in the first place.

The production of PVC involves combining chlorine with ethylene, which is obtained from oil, to form vinyl chloride monomer (VCM). Molecules of VCM are polymerised to form PVC resin, and additives are incorporated to give the PVC certain properties.

The two-mile long 32N train derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, on 3 February. It was carrying vinyl chloride from a chemicals plant in La Porte, just outside Houston, Texas, run by Oxy Vinyls, the chemical arm of Occidental Petroleum, according to shipment records released by the EPA. The chemicals were on a 1,600-mile journey from Oxy Vinyls’ plant in Deer Park, Texas, to its facility in Pedricktown, New Jersey, which makes plastic used in PVC flooring.

Vinyl chloride can be devastating for human health. According to a 2020 report published in the academic journal Cancer Spectrums, acute exposure to vinyl chloride can cause loss of consciousness, lung and kidney irritation, and, after sustained exposure, a rare form of liver cancer. The study also found that those living within 10 miles of a petrochemical facility face an increased risk of cancer as well as other health issues.

Emergency responders at the scene chose to incinerate the vinyl chloride to avert a wider explosion, but Enck questions whether it was “smart” to ignite over 100,000 gallons (around 440,000 litres) of vinyl chloride, which, when heated, can form phosgene, a chemical weapon used in World War One.

While US public health agency the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says it is possible to incinerate the chemical safely at a specific temperature in a controlled setting, experts have pointed out that it would have been impossible to control the burn completely. Enck says the more responsible option would have been to use vacuum trucks to remove the chemicals from the train cars.

Enck and Schade share concerns about why the EPA was originally slow to test for dioxins, which are formed when chlorine is burned – a common industrial process in the production of PVC. The chemicals are highly persistent and can accumulate and stay in the environment or human bodies for years. The compounds are linked to illnesses including diabetes, heart disease and nervous system disorders. They are also notorious for being the primary contaminant in Agent Orange.

“When you burn chlorinated chemicals and materials, especially in an uncontrolled environment like we saw in East Palestine, that’s really a perfect recipe for dioxins,” says Schade.

Enck believes the EPA has “a culture as an agency to defer to states. They probably deferred to Ohio EPA, and I don’t think Ohio EPA was well-equipped to make this decision.”

The EPA told E&T the local fire chief made the decision to burn the chemicals in consultation with the train operator Norfolk Southern, local law enforcement and response officials from Ohio. The EPA says its own personnel were present during meetings leading up to the burning of the chemicals, but “were not consulted about the controlled vent and burn during these ad hoc meetings”.

Enck also questions why the EPA waited until a month after the derailment to direct Norfolk Southern to test for dioxins. She also thinks it is “troubling” that the EPA directed the train operator to carry out the testing rather than doing it themselves.

The EPA says it is providing direct oversight of the monitoring and is carrying out some of its own tests to compare results for soil sampling with those reported by Norfolk Southern’s contractor. However, the EPA acknowledges that Norfolk Southern is not using the same real-time sampling technology the EPA has access to. The EPA says the operator has mobilised “some additional real-time sampling resources, which are being evaluated for effectiveness”.

The EPA says preliminary test results show dioxin levels in East Palestine are below the federal action thresholds, “although a few samples taken in public-rights-of-way have elevated levels of compounds”. However, Schade thinks testing the food supply chain will be vital.

“They need to be looking at other environmental media. For example, we know there are farms downwind of the derailment that could have been impacted,” he says. “They should be looking for dioxins in chickens, chicken eggs, cows, dairy products… because dioxins are extremely persistent and bioaccumulative – they build up in the food chain.”

Officials have recognised this possibility. At the beginning of April, the Ohio Department of Agriculture (ODA) and The Ohio State University (OSU) announced they would begin collecting plant tissue samples from farms in the area.

Community

Mossville

Mossville was an African-American community founded by Jack Moss, an ex-slave, in 1790. The town was settled by former enslaved Africans, who were granted the land through a ‘fee-simple title acquired by squatters’ rights’. In this manner, anyone who agreed to improve the property while residing for a specified number of years could attain ownership.

Petrochemical and industrial plants moved into the area in the 1940s and ’50s and in 2000, South African petrochemical giant Sasol moved its operations there. The Sasol industrial complex is over three square miles with an estimated value of $8.1bn. Sasol swallowed up swathes of old Mossville through a controversial voluntary land purchase programme, deforested the land and expanded its production.

Large portions of Mossville’s population also had to be relocated in the 1990s after the groundwater was found to be contaminated, notes Schade.

“It is a classic case of environmental injustice and racism,” says Schade. He notes that studies of Mossville have documented that residents were exposed to elevated concentrations of dioxins, while dioxins were also found in the food supply chain.

Mossville Image credit: Alamy

Following the derailment, according to the Ohio Department of Health, East Palestine residents reported headaches, coughing, fatigue, irritation and burning of the skin. A whole month after the derailment, seven CDC investigators that had formed part of a team conducting house-to-house interviews in the area also became ill.

Monica Unseld, a biologist and executive director of Louisville-based non-profit Until Justice Data Partners, says response from authorities is part of a systemic problem. “In the US, we don’t typically test chemicals for safety before we put them on the market. Americans are born with hundreds of chemicals already in their bodies,” she says.

Unseld says whatever testing that is done often looks at chemicals one at a time, “so we’re not testing for mixture. When we test the water, we don’t perhaps see vinyl chloride, maybe we are seeing vinyl chloride broken down and its elements are combined with something else…this could be a reason we are not finding high levels of the chemical in the environment,” she explains.

Dioxins can also act as endocrine disrupters, which can interfere with the body’s hormones, notes Unseld, “and a lot of them have not yet been well studied, so it’s difficult to say with any certainty that the soil is safe”.

Unseld thinks that, given the uncertainty around testing, authorities should take symptoms in the community seriously. “We don’t have the appropriate testing in place, and we can’t really talk about health thresholds because we don’t talk about lived experience data,” she says.

It is not just during the production phase that PVC is dangerous. The use of PVC products also pose health risks to consumers. “PVC plastic is often filled with a witches’ brew of toxic additives such as lead, cadmium, phthalates,” says Schade.

Phthalates, which are endocrine disrupters, give the PVC a flexible property. They are found at elevated concentrations in products such as vinyl shower curtains. The quintessential children’s bathtime toy, the rubber duck, is also made of PVC.

Unseld says exposure to these chemicals is often gradual. “PVC is used in building materials and water pipes, so it can leach into your drinking water, but it is also in our credit cards. With endocrine disruption, we look at long-term low-dose experience; most tests don’t look for endocrine disrupters because they are such low doses.”

The CDC says more research is needed to assess the human health effects of exposure to phthalates. However, it has carried out research which indicates that phthalate exposure is widespread in the US population. The CDC says black populations had higher levels of exposure compared to the average.

There is no safe way to dispose of vinyl plastic materials, according to Toxic-Free Future. In the research report ‘Vinyl chloride and toxic waste’, the non-profit found that vinyl chloride and PVC plastic plants sent more than 20 million pounds (9,000 tonnes) of chlorinated waste to incinerators in Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas in 2021. The incineration of chlorinated chemicals and materials can lead to the formation and release of dioxins. Dioxins are also released during accidental building and landfill fires involving PVC plastic.

“From production, to use, to disposal, PVC is an environmental nightmare,” says Schade.

Toxic-Free Future’s report found that, of the 373,262 US residents that live within three miles of a vinyl chloride, PVC manufacturing or PVC waste disposal facility, 63 per cent are people of colour. The report also found that these residents earn 37 per cent below the national average and 27 per cent are children, compared to the national average of 22 per cent – infants and children are particularly vulnerable to exposure to toxic chemicals.

“None of this is coincidence, it’s not an accident,” says Unseld. “Even here in Louisville, Kentucky, in an area known as ‘Rubbertown’, we have about a dozen high-risk facilities planned – these are the most dangerous types of facilities you can have.” There are already around 20 high-risk facilities in Rubbertown, which is made up of predominantly black communities. “People that live around Rubbertown live at least 12-13 years less than people that live less than 20 minutes away. There are higher asthma rates, higher cancer rates. This is happening all over America,” says Unseld.

Over the years, whole communities have been uprooted. Residents in at least four different communities in the state of Louisiana alone – Reveilletown, Morrisonville, Plaquemine and Mossville – have been forced to relocate due to vinyl chloride and contamination from vinyl/PVC plants.

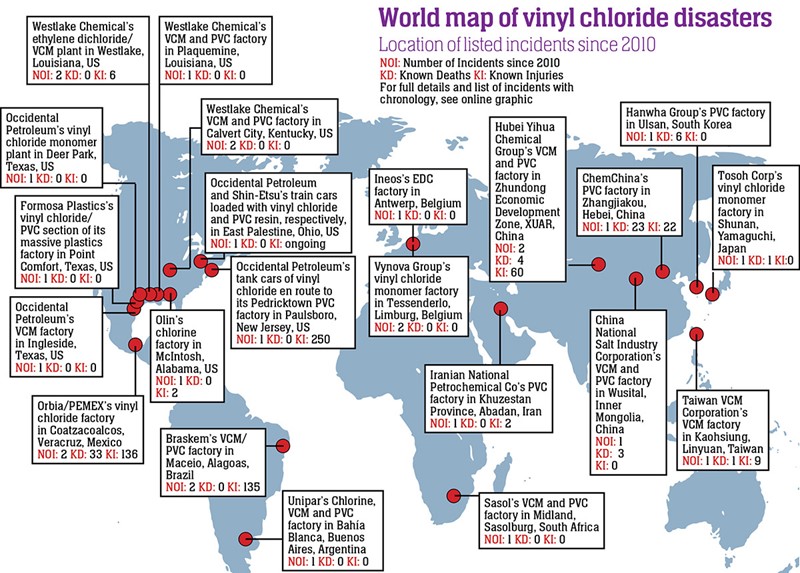

Map of vinyl chloride disasters since 2010. Source: Material Research L3C Image credit: Map of vinyl chloride disasters since 2010. Source: Material Research L3C

Oxy Vinyls has a history of accidents and near misses. Only in January, a tornado moved through the heart of the petrochemical industry east of Houston, with Oxy Vinyls’ VCM plant being in the storm’s path as charted by the National Weather Service.

A fire at the same plant last year raised concerns about the potential release of ethylene oxide, but no ‘protective measures’ for the community were advised by officials. And in 2012, a train carrying vinyl chloride – bound for the same plastics plant in New Jersey that was the destination of the Ohio train – derailed and plunged into a creek, releasing 23,000 gallons of the chemical and prompting evacuations of nearby homes.

A recent analysis by the low-profit open-access data company Material Research for the non-profit Coming Clean found that, since 2010, there have been at least 40 chemical incidents worldwide involving vinyl chloride and PVC. These have occurred at 29 facilities globally, almost half of which are in the US. Fires, leaks and explosions killed at least 71 people worldwide and injured 637 in the 40 incidents.

Yet petrochemical companies are ramping up the production of PVC. According to its regulatory filings last year, Oxy Vinyls plans to spend $1.1bn (£0.9bn) to expand and upgrade its La Porte plant in Texas. Shintech, the world’s largest producer of PVC, and whose shipments also burned in the Ohio disaster, is spending more than $2bn (£1.6bn) to expand operations in Texas and Louisiana.

An April report from campaign group Toxic Free Future found that Oxy Vinyls reported it released 59,679lb (27,070kg) of vinyl chloride into the air at its chemical plants in Texas, New Jersey and Niagara Falls in 2021. Shintech reported it released 45,250lb (20,525kg) of vinyl chloride into the air at its plants in Louisiana and Texas. The US’s top emitter of vinyl chloride, Westlake Chemical, reported releasing 185,807lb (84,280kg) of vinyl chloride into the air from its chemical plants in Kentucky, Louisiana and Mississippi in 2021.

Meanwhile, according to data from the Association for American Railroads, rail shipments of chemicals used in plastic production grew by about a third over the past decade. Chemicals have become a particularly important business for railways because one of their traditional mainstays, coal transportation, has fallen steeply with the decline in the mining and burning of coal. This is during a time where fears over rail safety have increased, with unions claiming more frequent disasters are likely while private rail companies continue to prioritise profit over safety.

Norfolk Southern and Oxy Vinyls failed to respond to requests for comment.

Insight

Fenceline communities

Communities that live adjacent to petrochemical facilities are known as fenceline communities. According to Unseld, people that live here are “more likely to be renters, and more likely to get a horrible mortgage deal with the bank”.

“When my ancestors were enslaved and you had the big plantation houses, they were out in those wood shelters – if they had any shelters at all – crammed in and living among the pigs and wildlife and the droppings.” Unseld says it is that “normalisation of people of colour not having clean, healthy stable shelter”, that is still present today with fenceline communities.

Unseld says tied up in the PVC problem is racism, classism and monopoly capitalism. She points out that many of the big US stores only sell bedsheets that contain plastic, meaning many people on lower incomes do not have a choice over the chemicals they expose themselves to. Then, she adds, “you have the fact that these chemicals should not be on the market anyway”.

There is a growing movement to reduce the harm done by PVC. Enck’s organisation, Beyond Plastics, launched a petition in March calling for the EPA to ban the material. “The toxic train derailment should be a wake-up call to the American public: vinyl chloride is an unnecessary and dangerous threat to our health, and it’s past time for the EPA to ban this known carcinogen from drinking-water pipes, packaging and toys our children chew on,” she says.

Some companies have already said they will eliminate the use of PVC in their products. In January 2022, the US Plastics Pact, a group endorsed by 100 major consumer companies, including Walmart, Target and Unilever, made a voluntary commitment to stop using PVC in their plastic packaging by 2025.

Where voluntary agreements fail to work, legislators will need to step in. Some cities in the US, including New York, Boston, Seattle and San Francisco, have adopted policies aimed at phasing out the use of PVC, limiting public purchases and mandating alternatives. A handful of countries, including Canada, Spain and South Korea, have restricted or banned the use of PVC packaging, and legislators have pursued a similar ban in California. Sweden, which adopted restrictions on PVC use almost three decades ago, is phasing out its use altogether.

Unseld adds: “Every step of the fossil fuel plastics lifestyle is deadly, so bans on individual chemicals and products won’t be enough because they’ll just replace it with something else. That’s why they moved lead out of paint into plastic toys.” She says fossil fuel companies will continue to scrape the barrel for chemicals – especially once energy is decarbonised – to create plastic.

There is only one solution, she says: “Just keep fossil fuels in the ground.”

Sign up to the E&T News e-mail to get great stories like this delivered to your inbox every day.