Roma communities driven from Romania’s booming city of Cluj-Napoca say the authorities treat them like human garbage.

Beside the airport on the outskirts of Cluj-Napoca, one of Romania’s fastest growing cities, lies an enormous landfill site. As you fly in, it’s easy to miss the multicolored roofs scattered between rolling green turf and mounds of waste. But at ground level, the area is teeming with life. Horse-drawn carts cross paths with empty garbage trucks returning to the city. Barefoot children run between makeshift wooden houses and crows circle overhead. This is Pata Rât, the country’s biggest landfill and long one of its most glaring environmental sins. For decades, pollution leached from untreated waste and garbage fires blazed, occasionally killing the occupants of those wooden shacks. Under pressure from the EU, the city began work on closing the site in 2015. Some 2.5 million tons of waste, accumulated over 70 years and covering an area the size of 27 football pitches were turfed over, and at the end of 2019, the local authorities declared Pata Rât “history.” Yet for the 1,500 Roma people still living here, Pata Rât is very much alive. And so is the environmental hazard on their doorstep. Two “temporary storage” landfills set up beside the old one in 2015 are still growing steadily, and experts say the old waste was never properly dealt with. “This was not an ecological landfill, it was not built in line with European standards,” Nodis says. “All these toxic substances went into the soil, into the groundwater. Everything in the area is polluted.” ‘Temporary’ landfills next to the original Pata Rât dump have been steadily growing for the last five years and more Driven from the city The Roma residents of Pata Rât began to arrive in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Some were driven by poverty to move to the landfill and work as waste pickers, but most have come in successive waves of evictions since Cluj-Napoca began to see a real estate boom in the 2000s. The last was in 2010, when local authorities evicted 350 inhabitants from Coastei Street near the city center. Linda Greta Zsiga remembers the cold December morning when she and her family were woken by police, city officials and bulldozers at their door. Just two days before, they and 75 other Roma families living on the street had been given notice of their eviction. Their new home was to be a complex of small, modular units nestled between the between Pata Rât’s existing camps. Linda Greta Zsiga says the Romanian authorities have treated her community like garbage Zsiga says the Roma community on Coastei Street was well integrated. They had been there for generations, they paid rent and utilities on their publicly owned homes, and their children attended local schools and kindergartens. Yet suddenly they were being dumped on the city’s trash heap. “They considered us garbage, not humans,” Zsiga says, “and they thought we deserve to live there.” Europe’s largest ethnic minority exposed to environmental hazards Responding to a survey last year, seven out of 10 Romanians said they don’t trust the Roma. Between 20% and 30% said Roma people have too many rights, that the state should be allowed to use violence against Roma, or that discrimination and hate speech against the Roma should not be punished. Such attitudes are not unique to Romania. Across Europe, racism against the continent’s largest ethnic minority results in denial of basic civil rights, exclusion from employment and public services, and — perhaps most strikingly — the marginalization of Roma communities to areas that lack adequate water, sanitation and waste management. Often, these sites are also in hazardous locations. A study published last year by the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) on “environmental racism against Roma communities in Central and Eastern Europe,” found that the Roma were “disproportionately exposed to environmental degradation and pollution stemming from waste dumps and landfills, contaminated sites, or dirty industries.” Cramped, dirty and cut off Arriving at Pata Rât, Zsiga found her extended family — 12 people altogether — crammed into a 16-square-meter room. Space was so cramped, they had to keep most of their belongings outside. They shared a single toilet and cold-water shower with the inhabitants of three other similarly overcrowded rooms. Zsiga remembers gazing out of her window across a sea of garbage. “There were no doves, no trees,” she says. “I love nature.” A 2012 report by the UN Development Programme found that 22% of adults there suffered from chronic disease or some form of disability. Researchers documented high incidence of skin infections, asthma, bronchitis, high blood pressure, heart and stomach problems, and a report European Roma Rights Centre found that over two years following their eviction, reported health problems more than doubled among the Coastei community. The oldest camp at Pata Rât is called ‘Dallas’ after the US soap opera. Driven by poverty, Roma began arriving here in the late 1960s to live off the landfill as waste pickers The EEB study describes one of the major factors in environmental racism against the Roma as forced eviction from “places with high economic value.” The Coastei community wasn’t given a reason for their eviction. But Zsiga has no doubt why they were moved. “They wanted to ‘clean’ Cluj of Roma,” she says. “Now very few Roma still live in the city.” The municipality of Cluj-Napoca told DW that they are cleaning up Pata Rât and providing health and other services to the community. They also stated that they are trying to prevent evictions and are partners in a program providing housing for 30 families, although they are not providing funding to the scheme. Waste-pickers put out of business There isn’t any solid health data from Pata Rât since the landfill was covered over, but an NGO worker in the area said respiratory diseases remain common, including among children. And economically, the closure of the dump has made life in Pata Rât even harder. Adela Ludvig, a 28-year-old mother of four, has lived beside the landfill for as long as she can remember. Her home is built from plywood, the roof an old canvas advertising banner — scrap materials collected from the dump. These days, her “villa” as Ludvig calls it, has a view onto a chemical waste dump covered in blue plastic foil and protected by barbed wire. Adela Ludvig and her children outside the home she built from scrap materials found on the landfill Ludvig used to collect plastic bottles and foil, cans and cardboard. She says a local recycling company paid the equivalent of €0.12 ($0.14) for a kilo of plastic, meaning she could make €40 in a day. “I could buy food,” she says, “or medicine, when the children needed it.” But the new “temporary” dumps are fenced off. When the landfill closed, waste pickers like Ludvig were left without work. “People were crying with hunger,” she says. Ludvig and her children — she has a fifth on the way — now live on the €220 she gets in child benefits each month. The nearest source of water is several hundred meters away and she has to visit it four or five times a day to meet her family’s needs. They have access to a power generator but cannot afford to pay for gasoline. Pata Rât communities fight back A year after the landfill was declared “history,” the major of Cluj-Napoca promised that the Pata Rât camps would “disappear by 2030” — without giving any indication of what is to happen to the 350 families living there. But well before his announcement, residents had been taking matters into their own hands. In 2012, Zsiga and others from Coastei camp set up an association that’s working with other NGOs to campaign for housing solutions for Pata Rât, and suing the authorities over the evictions. They are currently awaiting a decision on their case from the European Court of Human Rights. The grassy meadows of Pata Rât might look picturesque, but environmental scientists warn that the site is still contaminated by untreated waste And thanks to an initiative supported by Norway Grants (by which the Norwegian government funds social projects in southern and eastern Europe) 35 families from Coastei were moved to Cluj-Napoca or nearby villages between 2014 and 2017. Zsiga, her partner and children, now live in a three-room apartment in the city. But she hasn’t turned her back on Pata Rât. Her siblings and their families still live there and she’s working at the site to support another 30 families who will move in a second stage of the initiative. “I wish that no one is left in Pata Rât,” Zsiga says, “no one deserves to live there.”

Author Archives: David Evans

Plastic pollution kills Pacific sea species

SUVA: From endangered freshwater dolphins drowned by discarded fishing nets to elephants scavenging through rubbish, migratory species are among the most vulnerable to plastic pollution, a United Nations report on the Asia-Pacific region said on Tuesday, calling for greater action to cut waste.Plastic particles have infiltrated even the most remote and seemingly pristine regions of the planet with tiny fragments discovered inside fish in the deepest recesses of the ocean and peppering Arctic sea ice.The paper by the UN’s Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals focused on the impacts of plastic on freshwater species in rivers and on land animals and birds, which researchers said were often overlooked victims of humanity’s expanding trash crisis.

Spain backs global agreement to tackle marine plastic pollution

At a Ministerial Conference, Spain’s Ministry of Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge (MITECO) has advocated the need to create an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution to work on a global agreement to tackle marine plastic pollution.

The Ministerial Conference is organised by the governments of Ecuador, Germany, Ghana and Vietnam with support from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to address the challenge of marine plastic pollution. In particular, this meeting aims to prepare the ground for the fifth session (UNEA 5.2) of the United Nations Environment Assembly on this subject, to be held between 28 February and 2 March 2022.

Spain, in line with the common position of the European Union and most of the participating countries, considers it necessary to move towards a global international agreement to tackle this challenge. The Ministry’s Director General for Environmental Quality and Assessment, Ismael Aznar, Spain’s representative at the Conference, stressed that it is essential to work on an agreement that will make it possible to address aspects not covered by existing instruments, coordinate the efforts of the parties, establish new measures focused on prevention and create a framework for the development of national action plans. To this end, Spain has called for an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution to be set up at UNEA 5.2 to outline this agreement.

Aznar highlighted the measures adopted by Spain to tackle plastic pollution, in particular, those aimed at restricting single-use plastic articles in the Draft Law on Waste and Contaminated Land – currently in parliamentary procedure – and the measures to combat marine pollution included in the National Marine Strategies.

Ministerial Declaration

The Conference concluded with the adoption of a ministerial declaration aimed at demonstrating the rationale for a new comprehensive multilateral agreement at the UNEA, as well as the majority support for the proposal to establish an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee.

The Ministerial Declaration refers to the unsustainable production and consumption of plastic and its impacts on the environment, which require urgent attention. It stresses the need for a commitment to create a framework for international cooperation that includes coordinated actions to address the entire life cycle of plastic, involving all actors, including Governments, the plastics industry, the scientific community and civil society. It also stresses that it should address the specific needs of developing countries, in line with the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Cape Fur seal entanglement, the horrifying reality

In a recent study, Stellenbosch University’s (SU) Sea Search-Namibian Dolphin Project and Ocean Conservation Namibia (OCN) found that hundreds of Cape Fur seals are entangled each year, mainly in fishing lines and nets, causing horrific injuries and can result in a slow, painful death.

The study was part of an ongoing project to investigate the impact of pollution on fur seals in Namibia, and demonstrated that a high number of affected animals were pups and juveniles, which were mainly entangled around the neck by fishing line.

“Plastic pollution and particularly lost and discarded fishing nets are having a big impact to marine life. Once entangled, these seals face a very painful and uncertain future: finding food becomes harder and wounds can become deep and debilitating, and likely cause death in many cases,” co-director of the Namibian Dolphin Project and an Hon Senior Lecturer in the Department of Botany and Zoology at Stellenbosch University, Dr Tess Gridley said:

“Changes to policy could help, such as financial incentives to recover lines, safe disposal of nets and sustainable alternatives to plastics,” Dr Gridley adds.

Have a look at this short video, detailing Sea Search’s work on Cape fur seals together with Ocean Conservation Namibia. This is the devastating reality of the damage caused by plastics in the marine environment.

Sea Search is currently fundraising so they can continue their research into South Africa and continue conservation work. Make a difference today by pledging your support and donating to help undo some of the harm caused by humans at https://gofund.me/8cc1f09f.

This video contains graphic details that may upset sensitive viewers:

Watch it here:

Also read:

WATCH: Plastic pollution is endangering the lives of Cape Fur seals

Picture: Sea Search / Screenshot from video

Single-use plastic plates and cutlery to be banned in England

Plastics Single-use plastic plates and cutlery to be banned in England Polystyrene cups will also be banned but campaigners say action to cut plastic waste is ‘snail-paced’ Damian Carrington Environment editor @dpcarrington Fri 27 Aug 2021 17.30 EDT Single-use plastic plates and cutlery, and polystyrene cups will be banned in England under government plans, as …

Continue reading “Single-use plastic plates and cutlery to be banned in England”

Opinion: If we stop burning fossil fuels, will we end up with more plastic and toxic chemicals?

As the United States comes to grips with the climate crisis, fossil fuels will slowly recede from being primary sources of energy. That’s the good news. But the bad news is that the petrochemical industry is counting on greatly increasing the production of plastics and toxic chemicals made from fossil fuels to profit from its reserves of oil and gas.That transition is why the challenges of climate, plastic pollution and chemical toxicity — which at first might each seem like distinct problems — are actually interrelated and require a systems approach to resolve. The danger is that if we focus on only a single metric, like greenhouse gas emissions, we may unintentionally encourage the shift from fuel to plastics and chemicals that are also unsafe and unsustainable.Already, according to a 2018 report from the International Energy Agency, petrochemicals, which are made from petroleum and natural gas, “are rapidly becoming the largest driver of global oil demand.”Petrochemicals are ubiquitous in everyday products, and many of them are poisoning us and our children. Stain repellents, flame retardants, phthalates and other toxics are contributing to cancer, falling sperm counts, obesity and a host of neurological, reproductive and immune problems, research has shown.Epidemiological studies over the past decade have found, moreover, that exposure in utero and in childhood to chemicals used as flame retardants, called polybrominated diphenyl ethers, or PBDEs, has been linked to significant declines in IQ. These chemicals, widely used since the 1970s in the United States, were largely phased out in recent years. But they have persisted in the environment. And the push to phase out PBDEs led to “regrettable substitutions,” as the authors of one study put it, replacing one type of phased-out toxic flame retardant with another one that is also harmful.And plastics, of course, are inundating the planet.Global chemical production is predicted to double by 2030, according to the United Nations. Plastic production could jump three- to fourfold by 2050, according to a World Economic Forum report in 2016. By that year, the ocean is expected to contain, by weight, more plastic than fish.Garbage, including plastic waste, at a beach in Panama City in April.Uis Acosta/Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesPlastic waste at Zikim Beach, near Ashkelon, Israel, in 2019.Amir Cohen/ReutersA recent study by the Minderoo Foundation, which is working to end plastic waste, found that single-use plastics account for over a third of plastics produced every year. Ninety-eight percent are made from fossil fuels, according to the study.Fracking and cheap natural gas have made the United States one of the most profitable places in the world to make polyethylene — a common plastic used primarily for packaging. New ethane cracker plants are planned for Pennsylvania and Ohio. These plants turn ethane, a cheap byproduct of natural gas, or naphtha, a crude oil product, into ethylene to make single-use and other plastics.These facilities will depend on fossil fuels as their feedstock, and the resulting production of plastics will generate more greenhouse gases. More than nine million tons of additional annual ethylene capacity is coming online globally in 2021, according to the consulting firm McKinsey.If we think we have too much plastic now, we may well be drowning in it in a few decades. The petrochemical industry’s misleading messaging is that plastic waste gets recycled; if not, it’s the consumer’s fault; and the chemicals used in plastics are harmless.The reality is that plastic waste is often exported to places in Africa and Asia and elsewhere lacking the capacity to recycle or manage the waste. In the United States, this waste often ends up as garbage in landfills and as trash in rivers, along the sides of roads and in oceans. It also accumulates in the bodies of marine mammals, sea birds and humans.It doesn’t have to be that way. The federal government and industry have made large investments to create low-carbon fuels in recent decades. Similarly large investments are needed to develop safer chemicals and alternatives to plastics.With the Biden administration, which is committed to combating climate change, we have an opportunity to turn the ship around. An initial step should be to end subsidies to the oil and gas industry. This would raise the price of fossil fuels and the cost of producing petrochemicals, making renewable energy sources more competitive and potentially apply a brake to the growth of the petrochemical industry.President Biden should push for legislation in Congress that would pause the issuance of permits by the federal government for new or expanded plastic production facilities, refineries, incinerators, waste-to-energy plants and other petrochemical facilities. A pause of up to three years, as called for in the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act, would allow the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Academies of Sciences to study the cumulative impact of these facilities and to propose guidelines and standards aimed at protecting human health and the environment.We can draw on lessons from the European Union. The European Commission, the E.U.’s executive arm, recently proposed an aggressive plan to become carbon-neutral by 2050. It also has developed a plan to build a circular economy based on the reuse and recycling of products and to address the presence of hazardous chemicals in those products. Instead of building more plastic and chemical production facilities, companies should invest in innovative technologies to achieve circular production and reuse.We now have the leadership to combat the three-headed hydra of climate change, plastic pollution and toxic chemicals threatening us and our ecosystems. Now we need strong legislation and continued investment in research and technology to achieve a healthier planet for our children.Is one of your favorite places in your country being affected by climate change?Describe that place — a beloved campsite, the levee you run, a local market, the woods you explored as a child — and tell us in a brief voice mail why you love it: (+01) 405-804-1422. What does this place mean to you, how is it changing, and how do you feel seeing it reshaped by environmental issues?We are interested in hearing from the global community. Please include your country code with your phone number in your message so that we can reach you with any questions. We may use a portion of your message in a future article.Marty Mulvihill is a co-founder of the venture capital fund Safer Made and helped create the Center for Green Chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley. Gretta Goldenman is an environmental consultant and the board chair of the Green Science Policy Institute, where Arlene Blum is the executive director.The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

Environmental Law Centre calls for independent review of proposed B.C. petrochemical, plastics complex

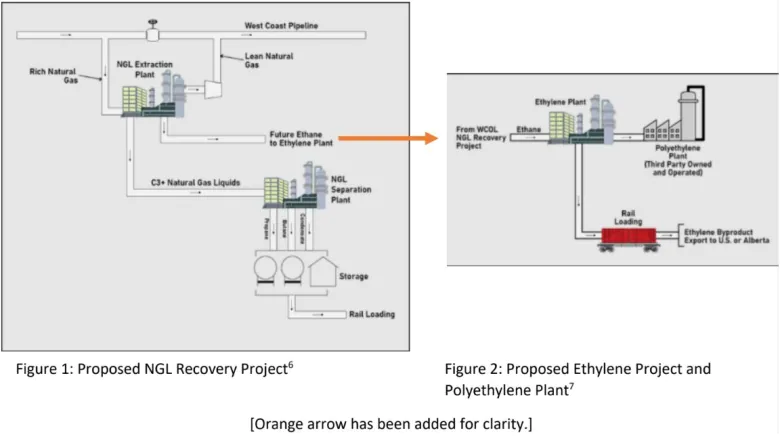

Lawyers at the University of Victoria Environmental Law Centre are calling for an independent assessment of three proposed petrochemical and plastics facilities in Prince George, B.C., that they say pose “profound risks to the global environment.” The request filed with Minister of the Environment and Climate Change Strategy George Heyman asks him to refer West Coast Olefins’ proposals for Prince George to an independent panel of experts that can assess the project in its entirety. UVic Environmental Law Centre legal director Calvin Sandborn said he’s optimistic Heyman will agree with the filing “because it would be irrational to proceed with the largest project in Prince George history without an independent panel conducting public hearings.” Calgary-based West Coast Olefins Ltd. has been quietly forging ahead with their plans for the $5.6 billion complex, putting together proposals for review by the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission and the Environmental Assessment process. The company’s website says an investment decision on the project will be made in 2022 and that the Environmental Assessment is in the early stages of determining the scope of information the company will be required to provide. A diagram of West Coast Olefins’s interconnected plants proposed for Prince George. The first would recover propane, butane and natural gas condensate (known as natural gas liquids or NGLs) from an existing gas pipeline then process NGLs into separate feed stocks. The second ethylene plant would process recovered ethane for use in a third plant to manufacture polyethylene, or plastic, products.

Fully recyclable paper cups? They exist, but you won’t find them at Starbucks

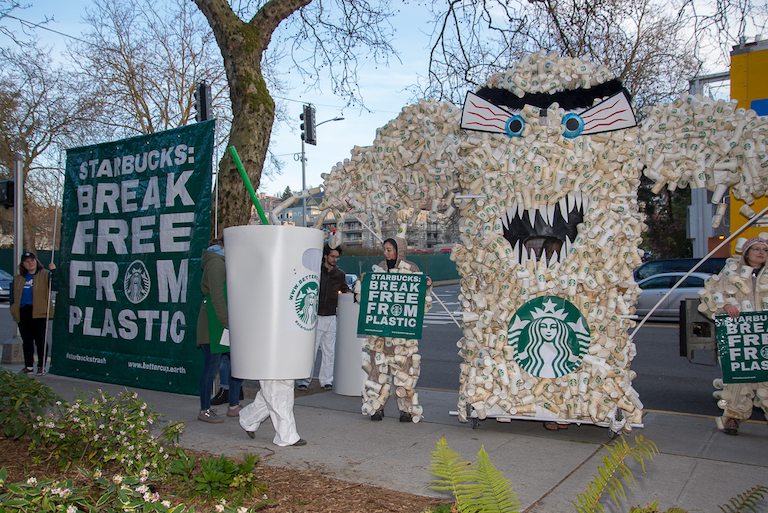

A new campaign draws attention to the fact that Starbucks cups are not truly recyclable due to a coating of polyethylene plastic on the inside of the cup.Starbucks has made several pledges to produce recyclable cups dating back to 2008 — but its cups are still unable to be recycled economically.Solutions already exist for fully recyclable cups, including a coating for paperboard barrier packaging that uses 40-51% less plastic. When you order your Venti-sized espresso macchiato at Starbucks, it will arrive in what looks and feels like a cardboard cup topped with a plastic lid. After you finish your drink, you might think about dumping your cup into a paper recycling bin. But you shouldn’t. Starbucks cups are actually lined with polyethylene plastic coating that makes it nearly impossible to recycle, experts say.

“Paper recycling is designed for recycling paper — not plastic,” Will Lorenzi, president of packaging engineering company Smart Planet Technologies, told Mongabay in an interview. “There’s a whole variety of products that have plastic coatings on it … and when those products hit the pulper [in a recycling plant] they block it up. It’s almost like a storm drain. If there’s a few leaves, a branch maybe, the storm drain is going to be fine. But if you get too many leaves and too many branches, all of a sudden the whole drain clogs up.”

It’s estimated that 1.6 million trees are logged each year to produce Starbucks cups, and that 4 million of these cups end up in landfills, according to Stand.Earth, a group that started

in 2016. Starbucks itself actually pledged to create a fully recyclable paper cup back in 2008, but nothing resulted from this commitment.

“So many people have confessed to us that they feel at least a little bit guilty about ordering a single-use coffee in a paper cup that came from critical forests,” Jim Ace, a senior campaigner and actions manager at Stand.Earth, told Mongabay in an email. “Many feel even worse when they learn it’s lined with polyethylene plastic, whether they are concerned for their own health or the health of the planet. Most consumers don’t realize Starbucks cups have been uneconomical to recycle, in part because they are lined with plastic, so they’ve ended up in landfills.”

Activists campaigning for Starbucks to produce a fully recyclable cup. Image by Stand.Earth.

According to a recent survey conducted in the U.S. by the SEAL Awards, which recognizes companies for their sustainability and environmental leadership, 83% of Starbucks customers actually believe that Starbucks cups can be recycled.

“At heart, the cup problem is a moral and leadership issue,” Matt Harney, founder of SEAL, said in a statement. “Like the 83% of consumers we surveyed, I recently thought that paper cups were, in fact, recyclable.”

Stand.Earth ended its campaign in 2019 when Starbucks partnered with other industry giants to support the NextGen Cup Challenge, which called on innovators to create a recyclable and compostable cup. Twelve winners were chosen, but two years later, the problem has still not been solved.

“Starbucks committed itself to solving its cup problem and have taken steps to develop solutions, but the majority of its customers still leave the store with single-use, disposable paper cups that are lined with plastic, which end up in the landfill,” Ace said. “Until that is solved, Starbucks still has a responsibility to address the problem.”

A commercially viable solution is already here, Lorenzi said. In 2016, his company, Smart Planet Technologies, developed EarthCoating, a film for paperboard barrier packaging that uses 40-51% less plastic than conventional plastic coating barriers.

“We came up with something that would basically be recyclable, and at the same time, work just as well as the current packaging we have,” Lorenzi said. The coating uses a special mix of minerals and resin so that the coating can easily be separated from the cardboard during the recycling process, and sink to the bottom of the pulper along with dirt and other residue, he added.

Several big companies, including United Airlines and Taco Bell in Australia, already use recyclable products with EarthCoating, Lorenzi said. Yet Starbucks has not adopted this technology, despite Smart Planet Technologies reaching out to Starbucks on several occasions.

Coffe cups lined with EarthCoding. Image courtesy of Smart Planet Technologies.

“They pretend we don’t exist,” Lorenzi said. “They pretend it’s not happening. They continue to do their own thing.”

On Starbucks’ website, the company pledges to “double the recycled content, recyclability and compostability, and reusability” of its cups and packaging by 2022.

Yet Lorenzi said he is not convinced this is a definitive goal. “It’s about the fifth date they set,” he said. “They started in 2008 — they were going to do it by 2012. And in 2010, they said they’d do it by 2015. In 2015, they said they’d do it by 2020. They’re now with the next one, which is 2022.”

Starbucks did not respond to Mongabay’s request for comment.

This month, the SEAL Awards Impact Team launched a campaign called #UpTheCup to call on Starbucks to truly adopt a recyclable cup. An accompanying petition has already garnered more than 60,000 signatures.

“In reality, as a society, we entrust leaders to make decisions — like the type of cup used — in a truly responsible way, even if that issue has gone undetected by the general public,” Harney said. “To quote C.S. Lewis, ‘Integrity is doing the right thing, even when no one is watching.’”

Banner image caption: Discarded food and beverage packaging. Image by Jasmin Sessler / Unsplash.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

How to fight microplastic pollution with magnets

Huge amounts of plastic ends up rivers and oceans every year, harming the environment and potentially also human health. But what if we could pull it out of water with the power of magnets?As a child, Fionn Ferreira spent hours exploring the coastline near his hometown of Ballydehob in south-west Ireland. But the more time he spent on the sheltered, shingle-strewn coves nearby, he grew increasingly shocked by the large amounts of plastic litter he found strewn across the beach and in the sea.

“It didn’t look nice to me – the coloured bits of plastic all along the shore,” he says.

Around the world, humans produce an estimated 300 million tonnes of plastic waste every year, and at least 10 million tonnes end up in our oceans – the equivalent of a rubbish truck load every minute.

But it was the plastic that Ferreira couldn’t see which really concerned him. Microplastics are fragments smaller than five millimetres and either come directly from the products we use or are created as larger plastic objects break down in the environment. They are ubiquitous – they have been found at the bottom of the world’s deepest ocean trench and lodged in Arctic sea ice.

“I got really anxious when I found out about microplastics,” says Ferreira, who is now aged 20 and a chemistry student at Groningen University in the Netherlands. “These plastics are going to be in our environment for thousands of years. We are going to be dealing with them long after we stop using plastic.”

As he learned more about the environmental impact of microplastics in the environment, Ferreira began to look for ways to combat them. And it was a serendipitous discovery on his local beach that gave him the idea for a new way to remove these tiny, omnipresent plastics from the oceans.Some shower products contain tiny plastic beads that when washed down the drain can escape into the environment where they are difficult to get rid of (Credit: Alamy)Microplastics are found in our clothes, cosmetics and cleaning products. One load of laundry can release an average of 700,000 microplastic fibres. Less than a millimetre in length, these fibres make their way into rivers and oceans, where they are eaten by fish and even corals. Because of their tiny size, microplastics are able to pass through filtration systems, making it very difficult to avoid them.

One 2018 study, plastic contamination can also be found in bottled water, with 93% of 259 bottled water samples the scientists examined containing microplastics.

According to recent research, we constantly inhale and ingest microplastics during our daily lives. One study in 2019 by researchers at the University of Newcastle found that globally people ingest an average of 5g of plastic every week – the equivalent of a credit card. The impact that this diet of microplastics has on our health, however, is still poorly understood.

Chemicals used in plastic have, however, been linked to a range of health problems including cancer, heart disease and poor foetal development. Studies have found that human exposure to microplastics could cause oxidative stress, inflammation and respiratory problems.

“The urgency of the plastic problem has not yet hit people,” says Ferreira. “Plastic pollution is a public health issue. You are not just drinking the plastic, but also the chemicals that are added to it. Plastic attracts heavy metals and brings these into our system.”

You might also want to read:

Why plastic waste is an ideal building material

The real price of getting rid of plastic packaging

The world’s first infinite plastic

Another concern is that plastics could help transport pathogens which bind themselves to the material. A 2016 study found the pathogen Vibrio cholerae, which causes cholera in humans, attached to microplastics sampled from the North and Baltic Seas.

“It is not just a problem of the health of our environment, but really a problem that concerns all of us and our health,” says Ferreira.And the amount of plastic in the environment is projected to get much worse. Plastic production is expected to increase by 60% by 2030 and triple by 2050. By then, there could be more plastic than fish in the ocean, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a UK non-profit that promotes the circular economy where materials are reused rather than thrown away.

At the age of 12 years old, Ferreira became determined to find a solution to remove microplastics from water. He started by designing his own spectrometer, a scientific instrument that uses ultraviolet light to measure the density of microplastics in solutions.

“I could see there were a lot of microplastics in the water and they weren’t just coming from big plastic breaking down in the sea,” he says. “There needed to be a way to combat this.”

It was on his local beach that Ferreira came up with a solution that could extract microplastics from water. “I found some oil spill residue with loads of plastic attached to it,” he says. “I realised that oil could be used to attract plastic.”

Ferreira mixed vegetable oil with iron oxide powder to create a magnetic liquid, also known as ferrofluid. He then blended in microplastics from a wide range of everyday items, including plastic bottles, paint and car tyres, and water from the washing machine.

After the microplastics attached themselves to the ferrofluid, Ferreira used a magnet to remove the solution and leave behind only water.

Following 5,000 tests, Ferreira’s method was 87% effective at extracting microplastics from water.

Ferreira is currently in the process of designing a device which uses the magnetic extraction method to capture microplastics as water flows past it. The device will be small enough to fit inside waterpipes to continuously extract plastic fragments as water flows through them. He has also been working on a system that could be fitted to ships so they can extract plastics on the oceans.Microplastics are found in a wide range of cosmetics and toiletries, but can also come from synthetic clothing and larger plastic items as they break down (Credit: HP)”There is no current effective solution to remove microplastics in natural waterways,” says Anne-Marieke Eveleens, who created another device known as the Bubble Barrier, a tube device that can be installed on canals and rivers to trap larger plastic waste with a stream of bubbles that guides it to a catchment area, preventing it from entering the ocean. “Our Bubble Barrier is very effective at catching macroplastics and can catch microparticles of plastic as small as 1 mm. Fionn’s innovation has the capacity to remove all types of microplastics.”

In 2019, Ferreira presented his invention to a panel of expert judges at the Google Science Fair, which led to him winning the competition and receiving an educational scholarship of $50,000 (£36,400).

“He observed and tackled a problem he saw locally which has vast global significance,” says Larissa Kelly, Ferreira’s former science teacher at Schull Community College and his mentor for the Google Science Fair entry. “His invention, based on very simple components, is groundbreaking. It has powerful potential to provide solutions that will contribute to the worldwide effort to remove microplastics from the environment.”

“I started out as a lonely inventor,” says Ferreira. “After the Google Science Fair, I could all of a sudden speak to scientists – they gave me credit for what I had done. My idea was no longer a toy invented by a child.”

After receiving funding from the Footprint Coalition, which was founded by actor Robert Downey Jr, Ferreira started scaling up the technology so it could be used at wastewater treatment facilities and prevent microplastics from escaping into the ocean.

He is currently working with US company Stress Engineering to fine-tune his invention and design a device out of stainless steel, glass or recycled plastic. “We’re trying to make something where we are not creating more plastic pollution,” he says.Humanity produces millions of tonnes of plastic waste every year and a large amount of it escapes to pollute natural habitats (Credit: Andrey Nekrasov/Getty Images)The technology is “very quick, cheap and low energy,” he says, adding that it can easily be integrated into existing facilities and is able to handle normal flow rates of water.

Ferreira is also developing a consumer-focused device which can be installed inside pipes in homes, cleaning the water as it enters and leaves the house. The aim is to provide people with water that is both safe to drink and sustainable.

“I don’t want to be drinking plastic every day,” he says. “By building this device in our homes, we are not only protecting our health, but also raising awareness.”

He is testing the devices in different water bodies around the world and hopes to commercialise both within the next two years.

But Ferreira says he has encountered scepticism throughout his journey as a young inventor and hopes that inventions such as his will help change that attitude. And as his generation inherits problems created by those that came before them, the world is likely to need more imaginative solutions.

“A lot of people don’t trust young inventors,” he says. “That needs to change. Youth have the power to come up with new creative ideas, they aren’t trained to look down just one tunnel.”

—

Bright Sparks Sustainability

This article is part of BBC Future’s Bright Sparks: Sustainability series, which sets out to find the young minds who are finding new and innovative ways of tackling environmental problems. They are the next generation of engineers, scientists and entrepreneurs who are taking control of their own future by seeking solutions to climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss and over-consumption.

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Appalachian communities talk gas, plastics, and inequity with federal energy officials

The U.S. Department of Energy held an online public meeting on Tuesday to find out how frontline communities in Appalachia are impacted by the growing ethane and petrochemical industries. Ethane is a byproduct of natural gas development and can be used to make plastics.

Sean O’Leary, senior researcher with the Ohio River Valley Institute, told the DOE that on balance, natural gas development, including pipelines and the ethane cracker being built by Shell in Beaver County to make plastic, are doing more harm than good.

“The environmental burdens currently being placed on the region, by the natural gas industry, and…by expansion of the petrochemical industry, are not only damaging to the well being of residents but have also failed to produce growth in jobs and prosperity,” O’Leary said in a presentation during the DOE meeting.

At the request of Congress, the Energy Department is producing a study on the environmental, health, and local impacts of ethane processing and distribution. It will also look at the potential economic benefits of increasing production, including more exports.

Following Pennsylvania Gas to Scotland

Amanda Woodrum, a researcher at Policy Matters Ohio, spoke on behalf of the coalition called ReImagine Appalachia. She told the DOE that Appalachia is rich in coal and natural gas, and has benefitted from union coal jobs. Still, she said it has been a resource curse. “Where Appalachia has essentially been providing the raw materials for the rest of the country, while itself has been left in poverty,” Woodrum said.

Woodrum pushed DOE for new infrastructure investments in the region.

Biden’s Effort Toward Environmental Justice and Climate Action

“We are determined to tackle these inequities,” said Dr. Jennifer Wilcox, DOE Acting Assistant Secretary of the newly renamed Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, which is leading the ethane report for Congress.

“For too long, frontline communities have suffered the negative health and social impacts associated with fossil energy infrastructure built through and around their neighborhoods,” she said. “And at the same time, they’ve been denied the energy access and economic benefits enjoyed in wealthier areas.”

The administration’s goal is to invest in communities impacted by fossil fuels, create good-paying jobs, and tackle climate change, according to Wilcox.

When it comes to ethane, U.S. production has nearly doubled since 2013, according to the Energy Information Administration, and demand is expected to continue an upward trend.

Climate and environmental groups are concerned about carbon emissions from this production.

“Deep decarbonization is the cornerstone of the president’s strategy,” Wilcox said during her opening comments at the ethane meeting. Biden has the goal of cutting carbon emissions in half by 2030 and creating a net-zero carbon economy by 2050. “And it means that we have to look at every sector across our economy: energy, transportation, and manufacturing,” she said.

The DOE ethane report, which will include comments from this meeting, is expected to be completed by the end of the year.

Energy Secretary Pushes Jobs in Coal and Natural Gas Communities From Climate Action

Video: As the World Grapples with Plastic Pollution, Pa.’s Ethane Cracker Promises More Plastic