Sahan Journal tells the stories of Minnesota’s immigrants and communities of color that no one else is telling. To receive a weekly email with a roundup of our stories, sign up for our free newsletter.

Processing…

Success! You’re on the list.

Whoops! There was an error and we couldn’t process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.

Most plastic waste in Minneapolis is not recycled, a new report has found, but instead is burned at a downtown incinerator adjacent to low-income communities of color, perpetuating a system in which vulnerable groups are exposed to high levels of pollution.

A mere 11 percent of plastic waste in Minneapolis is ultimately recycled, according to the July report, published by the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, an international organization that seeks to shut down garbage-burning-to-energy facilities such as the Hennepin Energy Recovery Center, better known as the HERC.

The report, “A Tale of Five Cities: Plastic Barriers to Zero Waste,” is a deep dive into plastics recycling in Minneapolis; Baltimore; Detroit; Long Beach, California; and Newark, New Jersey. Minneapolis ranks favorably among these cities. The report’s authors found that its municipal curbside single-sort recycling service ranked best in the group and the city’s recycling contractor, the nonprofit Eureka Recycling, was among the best in the nation.

Despite the success of Minneapolis’s recycling program, most plastics aren’t finding their way into the system to begin with. “Despite that infrastructure and despite the efforts, it’s still demonstrating that the majority of plastic in the waste stream either isn’t recyclable in the first place or it’s not being recycled and is being burned or landfilled,” said Akira Yano, an organizer with Minnesota Environmental Justice Table, a nonprofit group that advocates for vulnerable communities across the state.

Globally, 91 percent of all plastic produced is not recycled, according to the July report. And while around 35 percent of plastic in municipal waste streams in the United States has the potential to be recycled, just 8.8 percent of it actually is.

“Most plastic is designed to be dumped and burned,” said report author Denise Patel, U.S. Program Director with the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives.

What’s recycled

What can be recycled is determined by what substances have a viable resale market, according to Lynn Hoffman, co-president of Minneapolis-based Eureka Recycling, which has contracts for residential recycling with Minneapolis, St. Paul, and several other communities.

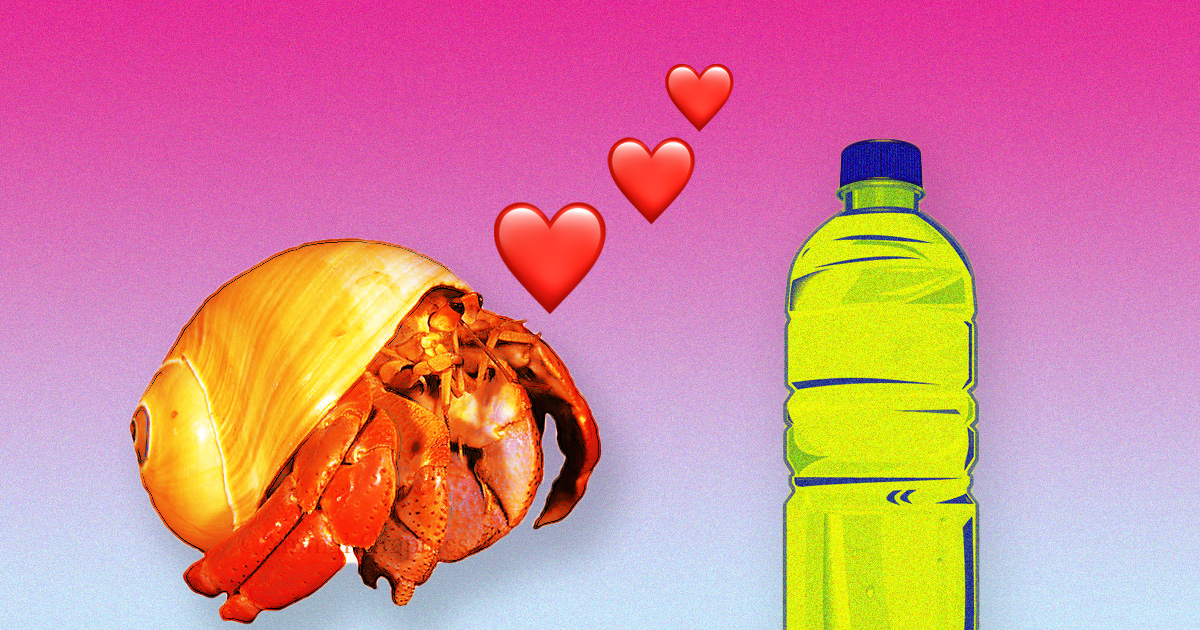

The resale markets for glass, paper, and metals are robust. But for plastics, the viability of the market depends on the base resin used to form the particular plastic. Plastic types #1 (think water or soda bottle), #2 (think milk jug or laundry detergent container), and #5 (think yogurt cups), have resale value and are typically recycled into new products.

But for less common plastics–such as types #3, #4, #6, and #7, used to make products like cling wrap, takeout containers, and CDs–there’s no real resale market, and the substances will likely be burned or landfilled. Plastic film used to make shopping bags is also largely non-recyclable and is only typically collected for reuse at grocery stores.

Despite the fact that only certain types of plastic are in demand and can be economically recycled, packaging and products that fall outside the desirable categories are often labeled with the recycling symbol of three arrows. That can be deceiving to consumers who believe the product they are tossing in a bin can be reused.

“It’s a huge challenge we have in communications,” said Kellie Kish, recycling coordinator for the city of Minneapolis.

Many recycling haulers attempt to simplify the process by telling people to put all types of plastic in their bins, Hoffman said. But Eureka requires its partner-cities to clearly state which types of plastic can be accepted: types #1, #2, and #5. In Minneapolis, that appears to be working. The Five Cities report found that 88 percent of plastic collected in the city’s single-sort system is recycled.

For Eureka, the biggest challenge is posed by plastic bags. The company spends countless hours and an estimated $75,000 per year sorting out and disposing of plastic bags, which can get caught in the sorting axles, and even catch fire, at their facility. Black plastics also are non-recyclable, because the laser reader Eureka uses to sort materials can’t determine which type of plastics they are,and they have a lower resale value on the market.

Packing wrap from companies like Amazon and Hello Fresh might be covered in the three-arrow symbol, but it’s not actually recyclable, Hoffman said. “That is egregious.”

A breakdown of where plastic waste in Minneapolis ultimately goes shows that most is destined for the trash. Source: Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives.

Connecting the dots

The Minnesota Environmental Justice Table is actively campaigning to shut down all seven garbage incinerators in the state, most prominently the HERC in Minneapolis. In Minnesota, incinerators that burn trash to make steam, which is converted into energy, are considered renewable energy sources, which experts say is misleading.

Want more? Get news and stories that illuminate the lives and experiences of Minnesota’s immigrants and communities of color.

Processing…

Success! You’re on the list.

Whoops! There was an error and we couldn’t process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.

Incinerators produce toxic air pollutants with demonstrated links to asthma, lung disease, high blood pressure, and heart disease. Environmental justice advocates have organized against the HERC for decades, citing its location on the edge of downtown, near north Minneapolis.

The HERC emits pollution—including arsenic, chromium, and particulate matter–onto north Minneapolis, a community where the majority of residents are people of color, and an area already exposed to a disproportionate level of air-borne toxins. Some of those toxins come from burning plastic, according to the Five Cities report, since about 88 percent of all plastic in Minneapolis ends up in the trash.

Fossil fuels are refined into ethane and propane and used to create plastics. Because plastic stems from fossil fuels like crude oil and gas, the Minnesota Environmental Justice Table sees the zero waste movement as being directly tied to the resistance against the Line 3 oil pipeline being constructed in Northern Minnesota. Both the construction of the pipeline through Ojibwe land and the burning of plastics near vulnerable communities of color exacerbate existing inequalities in who suffers from pollution, said organizer Yano.

“The fight against Line 3 and the fight against the HERC are linked, because the construction of Line 3 would reinforce the use of fossil fuels to continue creating unsustainable plastic products,” Yano said.

Move to zero waste

Clearly, the status quo of plastics recycling is bad for the planet, but experts and advocates believe a zero waste future is possible.

“What we do now with the plastic waste, it’s not sustainable,” said Professor Muhammad Rabnawaz, who studies plastics at the Michigan State University School of Packaging.

Rabnawaz’s research looks at alternatives to plastic packaging, which is a growing field in the United States. In 2018, China stopped accepting plastic waste from the U. S., forcing the government and scientists to reexamine how to manage excess plastic. Rabnawaz believes the federal government is moving in the right direction on plastic recycling.

Finding value for types of plastic beyond #1, #2, and #5, is key to improving recycling. Rabnawaz said regulating the number of plastic types that can be used on one product would be an important step, because some items have multiple plastic categories and are impossible to recycle.

Increased community education is key to reducing plastic waste, Rabnawaz said. He favors an approach that provides tax incentives for using plastic alternatives and requirements that reintroduce recycled plastic into manufacturing.

“It’s all about engaging all stakeholders to envision and create a new future with plastic designed for recycling and biodegradability and where possible using paper and metal as alternatives,” Rabnawaz, a PhD originally from Pakistan, told Sahan Journal.

Eureka has advocated for Minnesota lawmakers to institute a statewide plastic bag ban and would like to see national legislation on truth-in-labeling so companies can’t greenwash their packaging with deceptive recycling symbols. Hoffman, the company’s co-president, said she also favors laws like one passed recently in California that require all plastic bottles to be made with at least 40 percent recycled material.

In Minneapolis, Kish and other city staff are conducting active outreach to educate residents about recycling best practices and the harms of plastic waste. Many city residents are serious about avoiding plastic and putting pressure on companies to use less, which helps.

In July, Maine signed the nation’s first extended producer responsibility law for packaging, which aims to incentivize companies to use packaging that is easier to recycle and mandates producers make payments to environmental stewardship organizations. Kish said that model is an exciting development in the fight against plastic waste.

For community advocates like Environmental Justice Table, pressuring Hennepin County to close the HERC is seen as a major step toward getting serious about reducing plastic pollution and moving to zero waste. If the HERC closes, Yano said, further action will follow.

“There needs to be increased transparency in how our waste is handled in the first place,” he said.

Sahan Journal publishes deep, reported news about immigrants and communities of color — the kind of stories you won’t find anywhere else. We don’t hide our community-centered reporting behind a paywall: We want it to be free for everyone. But this kind of journalism is expensive to produce and we can’t do this critical work without your help. That is why we rely on the generosity of readers like you to support our nonprofit newsroom.

Become a monthly donor today to help us continue to provide award-winning reporting to our community. Thank you.