Single-use plastics prioritize convenience. The energy put into making single-use plastics is wasted after just one use. This creates a constant demand and fuels a vicious cycle that drives climate change. In this article, we’re going to answer some of your questions around single-use plastics and climate change, including: How do single-use plastics relate to …

Author Archives: David Evans

Recycling Plastic & Climate Change

Recycling is a powerful tool that can help mitigate the effects of climate change, especially when recycling plastics. In this article, we’re going to break down the relationship between recycling plastic and climate change. How does plastic contribute to climate change? Plastics are derived from fossil fuels. The plastic polymers are refined from petroleum and …

Ocean Plastic & Climate Change

When we think of plastic pollution in the ocean, we usually imagine how it affects wildlife. But as it turns out, ocean plastics actually have a significant effect on climate change. In this article, we’re going to break down the three factors that tie ocean plastic to climate change: Plastic manufacturing Plastic decomposition in the …

Does Burning Plastic Cause Climate Change?

The process of burning plastic is touted as a way to both generate electricity and get rid of plastic pollution. While it does kill two birds with one stone, the practice has seriously harmful side effects that far outweigh the benefits. Plastic incineration is responsible for: Contributing to climate change Releasing toxic gasses and chemicals …

Continue reading “Does Burning Plastic Cause Climate Change?”

Dead turtles and waves of plastic show Sri Lankan ship disaster's deep ramifications

The Singapore-flagged X-Press Pearl caught fire on May 20 en route to Colombo carrying 350 metric tons of oil in its tanks and at least 81 containers of “dangerous goods,” including nitric acid — a highly toxic chemical used to make fertilizers. As the Sri Lankan navy and coast guard teams fought to douse the flames, the inferno tore through the ship’s cargo, releasing a cocktail of hazardous chemicals into the air and sea, prompting authorities to issue a toxic rain alert, and compounding fears of an oil spill.The fire released 80 tons of plastic pellets — raw materials used to make plastic products — into the ocean, blanketing beaches along Sri Lanka’s western coast. The environmental impact was immediately clear.Plastic pellets became lodged in fish’s gills and mouths. And dozens of rare sea turtles washed up on Sri Lanka’s beaches, some with what appeared to be scorch marks on their shells. Fish, dolphins and even a whale were found dead. As of late June, about 200 carcasses had been counted. Two months on, billions of plastic particles have washed up on nearly every shore of the island and are expected to disperse throughout the Indian Ocean.Fishing communities have been heavily impacted, and locals fear it will be take years for the island to recover from what environmentalists have called the worst disaster in Sri Lanka’s history. Animal deathsSri Lanka is a tourist hotspot. Its unspoiled beaches and turquoise waters not only attract tourists, they are home to abundant sea life, including 28 species of marine mammals, such as blue whales and five species of endangered nesting turtles. It is not unusual for marine animals to wash ashore at this time of year, after becoming entangled in fishing nets or simply victims of the rough monsoon seas. While no records were kept of how many dead animals washed ashore in previous years, local environmentalists say this time is different. “We are seeing this exponential increase of marine deaths, including dolphins, turtles. What is noticeable is the exponential increase started soon after this accident,” said Don Muditha Katuwawala, coordinator for Sri Lankan marine conservation group Pearl Protectors. “We are seeing 30 to 40 cases reported daily.”Thushan Kapurusinghe, a turtle conservationist with 28 years’ experience who helped establish Sri Lanka’s first marine turtle sanctuary, believes the deaths were caused by the ship disaster. Usually, if a turtle was caught in a net or rough seas, Kapurusinghe said, you’d see cut marks on their fins or broken shells. Often they are bloated from weeks in the water or have bite marks from other predators, he said. But the turtles he has seen on the beaches, and in photos sent to him from residents, had apparent scorch marks on their shells, swollen eyes and salt glands, and red engorged blood vessels and legions around their mouths and bellies, he said. “What you can see with most of these turtles found along the beaches in recent weeks, particularly after the X-Press Pearl disaster, these are fresh specimens,” he said. “Now when you see newly dead carcasses, there are clear burn marks on top of the shell … Around the mouth you can see red patches and bleeding, that means internally they are bleeding.”He said this suggests they may have been exposed to chemicals or injured in the fire. Sri Lanka is home to leatherback turtles, green turtles, loggerheads, hawksbill and the small Olive Ridley turtle. Kapurusinghe, the conservationist, said most of the turtles washing up are the latter — among the world’s smallest sea turtles. From images he’s seen, most are juveniles, which spend their days feeding in the shallower waters close to the western coast, he said. While nesting sites are found all over the coast, turtle migration and nesting routes, he said, start at the southern coast and make their way north up Sri Lanka’s western coast between March and July. The carcasses were found on beaches around the capital Colombo — up the western shoreline — where the ship was. “This is not normal. When you observe them you can say they did not die because of becoming tangled in fishing nets,” he said. .m-infographic_1625816718976{background:url(//cdn.cnn.com/cnn/.e/interactive/html5-video-media/2021/07/09/20210603-Sri-Lanka-sinking-ship-map-smallx2-new.png) no-repeat 0 0 transparent;margin-bottom:30px;width:100%;-moz-background-size:cover;-o-background-size:cover;-webkit-background-size:cover;background-size:cover;font-size:0;}.m-infographic_1625816718976:before{content:””;display:block;padding-top:143.2%;}@media (min-width:640px) {.m-infographic_1625816718976 {background-image:url(//cdn.cnn.com/cnn/.e/interactive/html5-video-media/2021/07/09/20210603-Sri-Lanka-sinking-ship-map-mediumx2-new.png);}.m-infographic_1625816718976:before{padding-top:61.92%;}}@media (min-width:1120px) {.m-infographic_1625816718976 {background-image:url(//cdn.cnn.com/cnn/.e/interactive/html5-video-media/2021/07/09/20210603-Sri-Lanka-sinking-ship-map-mediumx2-new.png);}.m-infographic_1625816718976:before{padding-top:61.92%;}}Several prominent marine biologists have warned against jumping to conclusions about the animal deaths and urged the community to wait for necropsies — examinations of the carcasses — to be completed, though it is unclear when that will be.Other factors could be at play in the deaths, including reporter bias, when people are more likely to note carcasses as they’re acutely aware of the disaster.Ultimately, no one can be sure what is causing the deaths, said Katuwawala of Pearl Protectors, and a lack of comparable data is adding to the confusion. “We don’t have a proper base-line data that we can compare to previous years. Because of the lack of it and the delays in the post-mortems there is a lot of confusion as to understanding why these marine deaths are happening,” he said. “All this needs to be accounted for and tested as to how they died and what really caused this disaster for them.”Plastic disaster While necropsies are being carried out, Sri Lankans are still collecting tons of plastic pellets released during the fire.In the weeks after the fire, the surf, whipped up by monsoon seas, became thick with these white plastic pellets, also known as nurdles. The volume was so great that, in some areas, they washed up in knee-deep piles, with each wave bringing millions more ashore. When Asha de Vos, a marine biologist and founder of Sri Lankan NGO Oceanswell, saw the plastic pollution inundate the shores near her home, she started calling experts to figure out what was going to happen next. Lockdown prevented residents from going to the beaches to help out with the response, but they could assist in other ways, she said. “I could feel people’s frustration,” de Vos said. Her team set up a “nurdle tracker” so the community could send in photographs of what the beaches looked like before and after the plastic. The result exceeded expectations: “We got around 120 people sending photographs within a few days of the entire coastline,” she said. The next step was to figure out where the nurdles were going and create models to track their distribution around the island. People would send in images of beaches where they spotted the plastic, with dates and times. Together, they were quickly able to build a picture of how far and wide the plastic was traveling and plan to conduct monthly surveys on the concentration of plastic in certain areas and how it changes over time.One thing stood out. Among the white pellets they noticed some pieces had burned and fused in the fire, something they hadn’t seen in previous similar disasters and could increase the danger to the marine environment from potential toxins.”If we can try to understand the degradation of these nurdles, what’s going to happen to them, scientifically, then we have a sense of, okay, how long is this impact going to last? How long can we predict these impacts are going to be?” de Vos said. The problem is they just don’t know how much plastic was released into the water, and how much remained on the ship. “It’s still very patchy, and it’s still hard for us to really have a lot of those answers,” she said. The country’s Marine Environmental Protection Authority said in June it had removed 1,000 tons of debris along 200 kilometers (124 miles) of the coastlines, a triumphant, yet incremental portion of the total spillage. Lessons from DurbanExperts warn the pellets will wash up for years to come and become a permanent part of the currents and tides of the world’s oceans. In a similar disaster in South Africa in 2018, 49 tons of plastic nurdles spilled into the sea around Durban. A year after the spill, pellets were found more than 4,000 kilometers (2,485 miles) away on St Helena island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and two years later on shores of Western Australia, more than 8,000 kilometers (4,970 miles) away. Charitha Pattiaratchi, an oceanography professor with the University of Western Australia, said the pellets were the main pollutant from the ship disaster as “any of the other chemicals, even if they fell into the ocean would have diluted very quickly.”The plastic, he said, while not necessarily toxic, will remain in the ocean for years.”The nurdles will continue to be present in the surface waters of the Indian Ocean for many decades and will make landfall in many of the Indian Ocean countries (for example in Indonesia, India, Maldives, and Somalia) because of the reversing monsoon currents in the region,” Pattiaratchi said.Using high-resolution modeling, his team have been able to plot the course of the nurdles’ journey over the past two months.

#video_1626936880109{margin:20px 0;}

#video_1626936880109 video,#video_1626936880109 img{margin: 0; position: relative; width: 100%;}

.cap_1626936880109{-webkit-font-smoothing:antialiased;padding:0 0 5px 5px; font-size:16px; color:#595959;}

.cap_1626936880109:before{content:””;display: block;height: 1px;margin-top: 10px;margin-bottom: 10px;width: 80px;background-color: #C5C5C5;}

.cap_1626936880109 >span{color:#C5C5C5;}

@media(max-width:480px){.cap_1626936880109{padding-left: 10px;}}

Projection of the nurdle spread following X-Press Pearl disaster Credit: Charitha Pattiaratchi, University of Western Australia

Pattiaratchi said over time the nurdles will grind down to become microplastics, and plastic from the Durban incident is still found on the beaches of Western Australia. “If you go to the beach, you will find them if you’re looking for them. And that’s what will happen to these ones, it will be distributed along the most of the Indian Ocean, northern Indian Ocean countries, if you go looking for them, you will find them for years to come.”While the pellets are not necessarily toxic to humans, Pattiaratchi said they can further impact marine life by getting trapped in gills of fish, causing them to suffocate.Fisheries devastatedSri Lanka’s fisheries were also deeply affected. In some areas they were closed, worsening the financial losses from communities already suffering from pandemic lockdowns. Fear and confusion spread over whether the fish were safe to eat. “We also heard about what was in the ship and the chemicals, so we are scared. So now for weeks we have not consumed any seafood. The fishermen are saying its safe. But there is no guarantee,” said Sarika Dinali, a resident from Negombo beach.D.S. Fernando, a fisherman also in Negombo, said “now the situation is even worse.” “People are now scared of eating fish because it might be contaminated. Prices have also dropped drastically. The situation is hopeless,” he said. Others have urged the government to speed up testing on samples and be clear with the public. “We are most affected because people are refraining from buying fish. It is the government’s responsibility to do proper tests and educate the public on what’s going on. Otherwise people are afraid to consume fish,” said local fishing community leader Aruna Roshantha.The Sri Lankan government, Department of Fisheries and the MEPA have not responded to CNN’s requests for comment.On July 11, state Fisheries Minister Kanchana Wikesekera said Rs 420 million ($2.1 million) in compensation will be paid to fishermen as part of an interim claim from the X-Press Pearl. On July 12, X-press Feeders said made an initial payment, through the vessel owner’s P&I insurers, of $3.6 million to the Sri Lankan government to help compensate those affected by the consequences of the fire and sinking of the vessel.Investigation ongoingAs communities wait for answers, government and environmental investigators are determining the extent of the disaster. Independent and international oil experts are on site trying to ensure any oil remaining on the half-sunken ship does not spill into the environment, causing further disaster. “We continue to contribute to the cleanup and pollution mitigation efforts, having flown in additional oil spill response assets on a chartered flight from Singapore in response to a request from the UN-EU team in Colombo,” the ship’s operators said in a statement. Salvors remain at the wreck site on a 24-hour watch “to deal with any debris and report any form of a spill with drones deployed daily to help with the monitoring activities,” it said. Investigations into what caused the fire are ongoing, but the boat had one container of nitric acid — a highly toxic chemical used to make fertilizers — that was leaking. The captain of the ship, Vitaly Tyutkalo was arrested on June 14 and later released on bail, according to police spokesperson Deputy Inspector Ajith Rohana. He has been accused of allegedly violating the country’s Marine Environment Pollutions Act but hasn’t been formally charged.The government has named another 14 people as co-accused in cases over the damage caused, according to Reuters.Meanwhile, the Centre for Environmental Justice has filed a fundamental rights petition in the Sri Lankan Supreme Court.For decades, de Vos has been pushing for greater rules on ships that pass by Sri Lanka’s waters as part of her work to protect non-migratory blue whales.The southern coast of Sri Lanka is the main artery through the Indian Ocean, and one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world.Pushing such lanes farther out to sea or shift to cleaner fuel could help to avoid further disasters, de Vos said, and help safeguard the future of endangered turtles, too. “The shipping lanes were put in place at a time when we didn’t have this wealth of knowledge about species and how they use these areas, or about safety concerns,” said de Vos. “And now we do have to use the best available information, to try to understand how we can coexist in a way that will make sure that we’re doing a better job and looking after oceans.”For de Vos, community involvement is key to recovering from the disaster.”We come from a small island where fishing is what you use the ocean for. Recreational conservation wasn’t a big theme, traditionally. And so to shift that we need to give more people have the opportunity to engage.””I want to make sure the public is also well informed and not misinformed,” she said. “And that that is something that can happen in a crisis situation,” she said.

Living on Earth: Beyond the Headlines

Air Date: Week of July 23, 2021

stream/download this segment as an MP3 file

Trees in the Tongass National Forest on Revillagigedo Island near Ketchikan. Tongass is the largest U.S. National Forest at 16.7 million acres, making it a key carbon sequester. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

After President Trump removed the roadless rule and other protections for the Tongass National Forest, America’s largest national forest, the Biden administration is set to bring them back, Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News tells host Bobby Bascomb in this week’s Beyond the Headlines segment. They also talk about Maine becoming the first U.S. state to pass a law requiring packaging manufacturers rather than taxpayers to cover the costs of recycling. For the history segment they go back to the year 1931 when a swarm of grasshoppers overwhelmed farmers who were already struck by the Dust Bowl.

Transcript

BASCOMB: Well, it’s time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with environmental health news. That’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. We’re going to talk about a political football that is long standing, and over 9 million acres in size. And of course, we’re talking about the Tongass National Forest in the Alaska panhandle. The world’s largest old growth temperate rain forest had been largely protected by Bill Clinton’s roadless rule. There was a lot of back and forth between starting back with the Reagan administration to Clinton, to Bush to Obama, and then President Trump reversed the roadless rule. If you can’t build roads into a forest, you can’t cut down the trees and haul them out. And now President Biden in his first months in office is poised to reverse it back to the roadless rule and protect the Tongass.

BASCOMB: Well, that’s great news. I mean, the Tongass is absolutely huge. It’s the largest national forest in the country in full of just, you know, biodiversity, it’s a really unique habitat.

DYKSTRA: Huge and unique. Normally, we don’t think of the words temperate and rain forests going in the same place. But it’s a wet place that grows a lot and the trees grow big and the species are abundant. All of that was threatened by the revocation of the roadless rule by President Trump. This may restore protections that environmentalists hold dear. But at the same time, there are logging communities in the Alaska panhandle that would be angered by the inability to go back and create jobs in the Tongass.

BASCOMB: Yeah, well, hence the political football that it’s been for so long. Well, what else do you have for us this week?

Maine recently passed a law that will shift the recycling costs away from consumers to producers. This legislation comes at a time when according to the US Environmental Protection Agency packaging and recycling accounts for nearly ⅓ of all municipal and solid waste. (Photo: Michael Lehet, Flickr, CC BY ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Unprecedented for the US even though it’s being tried in a few Canadian provinces and in the EU, Maine becomes the first US state to set up a system to bill companies who produce a lot of packaging, for the disposal and recycling of that packaging. They’re doing that through a fund that they hope to create, where these companies would pay in, and municipalities would be subsidized for all the extra spending they have to do for recycling cardboard, plastic and other recyclables.

BASCOMB: Well, that’s great, though, I have to wonder where all that plastic recycling is supposed to go? You know, so many Asian countries aren’t taking it from the United States anymore. And you know, we don’t really have the infrastructure here.

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s no secret that plastics recycling has collapsed in recent years. The state of Maine has given itself till the end of 2023. To figure out how all this would work. Plastics recycling is in absolute worldwide turmoil. Cardboard recycling is a little bit easier and it’s still succeeding in a lot of places. But Maine is taking the first step in the US to try and manage all of the recycling business that has to take place.

BASCOMB: Well, I’ll be curious to see how it works out for them. I wish them luck. What do you have for us from the history books this week?

On July of 26, 1931 a swarm of grasshoppers devoured millions of acres of crops in Iowa, Nebraska and South Dakota, states which were already suffering from the Dust Bowl. (Photo: Your, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: We have a 90th anniversary, July 26, 1931. That was a very dry year, at the beginning of what became known as the Dust Bowl, and the perfect swarm was created. Not perfect storm, perfect swarm: grasshoppers by possibly the billions overwhelmed farmland in Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, cornfields were eaten straight down to the stubs. American agriculture was hit hard, not just by their grasshoppers, but by a drought that ended up lasting close to 10 years, the Great Depression, saw dust storms, crop failures, all of which were due in part to that long drought and in part due to just terrible soil conservation practices by American farmers. The farmers have cleaned up their act somewhat. And hopefully we’re not reemerging into another huge drought.

BASCOMB: Gosh, yeah, I mean, there is, of course, a terrible drought going on in much of the West. But, you know, let’s hope we’ve learned a thing or two in the last 90 years about you know, how to preserve the soil.

DYKSTRA: Let’s hope.

BASCOMB: Indeed. All right, well, thanks Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there’s more on these stories on the Living on Earth website, that’s loe.org.

Links

The Washington Post | “Biden Administration Proposes Sweeping Protections for Alaska’s Tongass National Forest” The Boston Globe | “Maine Passes Nation’s First Law to Make Big Companies Pay for the Cost of Recycling Their Packaging” History | “Grasshoppers Devastate Midwestern Crops”

Maine will make companies pay for recycling. Here's how it works

The law aims to take the cost burden of recycling away from taxpayers. One environmental advocate said the change could be “transformative.”Recycling, that feel-good moment when people put their paper and plastic in special bins, was a headache for municipal governments even in good times. And, only a small amount was actually getting recycled.Then, five years ago, China stopped buying most of America’s recycling, and dozens of cities across the United States suspended or weakened their recycling programs.Now, Maine has implemented a new law that could transform the way packaging is recycled by requiring manufacturers, rather than taxpayers, to cover the cost. Nearly a dozen states have been considering similar regulations and Oregon is about to sign its own version in coming weeks.Maine’s law “is transformative,” said Sarah Nichols, who leads the sustainability program at the Natural Resources Council of Maine. More fundamentally, “It’s going to be the difference between having a recycling program or not.”The recycling market is a commodities market and can be volatile. And, recycling has become extremely expensive for municipal governments. The idea behind the Maine and Oregon laws is that, with sufficient funding, more of what gets thrown away could be recycled instead of dumped in landfills or burned in incinerators. In other countries with such laws, that has proved to be the case.Essentially, these programs work by charging producers a fee based on a number of factors, including the tonnage of packaging they put on the market. Those fees are typically paid into a producer responsibility organization, a nonprofit group contracted and audited by the state. It reimburses municipal governments for their recycling operations with the fees collected from producers.Nearly all European Union member states, as well as Japan, South Korea and five Canadian provinces, have laws like these and they have seen their recycling rates soar and their collection programs remain resilient, even in the face of a collapse in the global recycling market caused in part by China’s decision in 2017 to stop importing other nations’ recyclables.Ireland’s recycling rate for plastics and paper products, for instance, rose from 19 percent in 2000 to 65 percent in 2017. Nearly every E.U. country with such programs has a recycling rate between 60 and 80 percent, according to an analysis by the Product Stewardship Institute. In 2018, the most recent year for which data is available, America’s recycling rate was 32 percent, a decline from a few years earlier.Nevertheless, laws like these have faced opposition from manufacturers, packaging-industry groups and retailers.In Maine, the packaging industry supported a competing bill that would have given producers more oversight of the program. It also would have exempted packaging for a range of pharmaceutical products and hazardous substances, including paint thinners, antifreeze and household cleaning products.One of the industry’s main objections to the bill that ultimately passed was that it gave the government too much authority and left the industry with not enough voice in the process. “No one knows packaging better than our members,” said Dan Felton, the executive director of the packaging industry group Ameripen, in a statement following the passage of the law. “Funds should be managed by industry.”Recycling is important for environmental reasons as well as in the fight against climate change. There are concerns that a growing market for plastics could drive demand for oil, contributing to the release of greenhouse gas emissions precisely at a time when the world needs to drastically cut emissions. By 2050, the plastics industry is expected to consume 20 percent of all the oil produced.The oil industry, concerned about declining demand as the world moves toward electric cars and away from fossil fuels, has pivoted toward making more plastic — spending more than $200 billion on chemical and plastic manufacturing plants in the United States. Vast amounts of plastic waste are exported to Africa and South Asia, where they often end up in dumps or in waterways and oceans. In the ocean, they can break down into microplastics that harm wildlife.China’s decision in 2017 precipitated a crisis in recycling. Without China as a market to import all that waste, recycling costs soared in the United States. Dozens of cities suspended their recycling programs or turned to landfilling and burning the recyclables they collected. In Oregon alone, 44 cities and 12 counties had to stop collecting certain plastics like polypropylene.Gov. Janet Mills of Maine, a Democrat, signed the new recycling policies into law this month.Robert F. Bukaty/Associated PressTo cope, state legislators and environmental protection agencies began looking for solutions. A number of them, including Maine and Oregon, settled on what is known as an extended producer responsibility program, or E.P.R., for packaging products.In Maine, packaging products covered by the law make up as much as 40 percent of the waste stream.In both states, one important benefit of the program is that it will make recycling more uniform statewide. Today, recycling is a patchwork, with variations between cities about what can be thrown in the recycling bin.These programs exist on a spectrum from producer-run and producer-controlled, to government-run. In Maine, the government is taking the lead, having the final say on how the program will be run, including setting the fees. In Oregon, the producer responsibility organization is expected to involve manufacturers to a larger degree, including them on an advisory council.In another key difference, Maine is also requiring producers to cover 100 percent of its municipalities’ recycling costs. Oregon, by contrast, will require producers to cover around 28 percent of the costs of recycling, with municipalities continuing to cover the rest.Built into both laws is an incentive for companies to reconsider the design and materials used in their packaging. A number of popular consumer products are hard to recycle, like disposable coffee cups — they’re made of a paper base, but with a plastic coating inside, and another plastic lid, as well as possibly a cardboard sleeve.Both Maine and Oregon are considering charging higher rates for packaging that is hard to recycle and therefore doesn’t have a recycling market or products that contain certain toxic chemicals, such as PFAS.For many companies, this might require a shift in mind-set.Scott Cassel, the founder of the Product Stewardship Institute and the former director of waste policy in Massachusetts, described the effect of one dairy company’s decision to change from a clear plastic milk bottle to an opaque white bottle. The opaque bottles were costlier to recycle, so the switch cost the government more money. “The choice of their container really matters,” Mr. Cassel said. “The producer of that product had their own reasons, but they didn’t consider the cost of the material to the recycling market.”Sorting plastics near Nairobi, Kenya. There is growing evidence that waste shipped to Africa and South Asia for recycling ends up in unregulated dumps or waterways.Baz Ratner/ReutersThirty-three states currently have extended producer responsibility laws on the books, but they are far more narrow. Typically they focus only on specific products, like used mattresses and tubs of paint.In those narrow applications, they have proven effective. Connecticut’s mattress, paint, electronic and thermostat E.P.R. programs have diverted more than 26 million pounds of waste since 2008, according to an analysis by the Product Stewardship Institute.A number of the packaging E.P.R. programs introduced in statehouses this year faced significant opposition from the packaging and retail industries, including the one in Maine. One of the industries’ main contentions was that the laws would lead to higher grocery prices for consumers. A study by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality of Canadian E.P.R. programs found that consumer product prices had increased by only $0.0056 per item.Some major consumer-product companies have begun voicing support for policies like these. In 2016, Greenpeace obtained internal documents from Coca-Cola Europe, which depicted extended producer responsibility as a policy that the company was fighting. In a sign of change, this spring, more than 100 multinational companies, including Coca-Cola, Unilever, and Walmart, signed a pledge committing to support E.P.R. policies.Sustainability and Climate Change: Join the Discussion The New York TimesOur Netting Zero series of virtual events brings together New York Times journalists with opinion leaders and experts to understand the challenges posed by global warming and to take the lead for change. Sign up for upcoming events or watch earlier discussions.

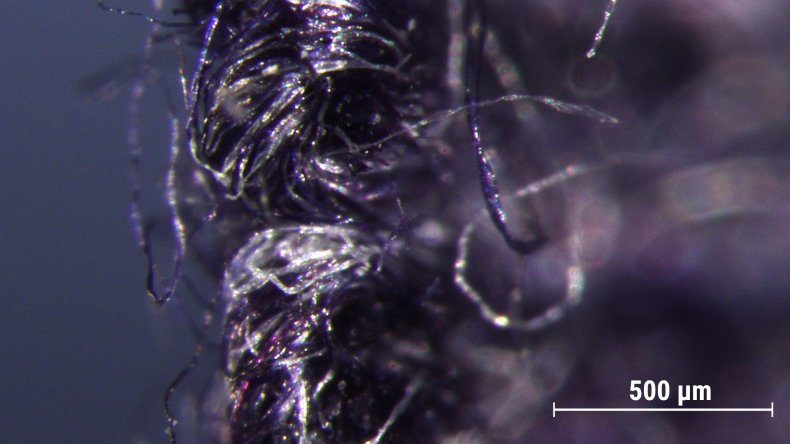

Microplastics wash out of your clothing and into the ocean. Some simple fixes could help

Every time we wash our synthetics, little bits of plastic leach out of our clothes, swirl down the drain, and make their way into the ocean.Those tiny shreds are called microfibres, a type of microplastic formed after larger materials have broken down. At five millimetres or smaller, they’re a growing problem in the world’s waters. They harm the food chain, showing up in plankton, the digestion systems of mammals, and seafood consumed by humans.A report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature found 35 per cent of primary microplastic pollution comes from synthetic clothing and textiles, with the remaining from cigarette butts, personal care products and other plastic products. In the Arctic of Eastern Canada, researchers found they were present in almost all water samples.Get top stories in your inbox.Our award-winning journalists bring you the news that impacts you, Canada, and the world. Don’t miss out.It’s part of the larger picture of Canada’s plastic problem, which sees 3.3 million tonnes of plastic thrown away each year, with only nine per cent making it to the recycling bin. However, a new study from Ocean Wise offers a hopeful perspective, says Laura Hardman, director of its Plastic Free Oceans campaign. The report, released this month, found microplastic can be significantly reduced by upgrading filters in washing machines. The new filters have the potential to catch up to 90 per cent of microfibres.Microfibres under a microscope. Image courtesy of Ocean WiseResearchers tested two types of lint traps, by LINTLUVR and Filtrol, which Hardman said most washing machine brands could incorporate into their existing systems to cut down on plastic waste. Clothing corporations could also use more-efficient filters and do a pre-wash before sending goods to consumers, the report suggests, since most fabrics shed the majority of their microfibres during the first wash. Also, an option is to have businesses vacuum away the particles during production. What people are reading Washing machine filters aren’t the be-all and end-all to solving microfibre pollution, but Hardman says they could be an effective and immediately available intervention. The filters can be used with any machine, although depending on the size of your machine hose, a pliable hose and clamp might be needed to fit the filter to the machine.“On average, 533 million microfibres are being released by your average Canadian and U.S. households and discharged into the environment. And that adds up to 85 quadrillion microfibres, believe it or not, into the wastewater annually in Canada in the U.S.,” she explained, referencing an earlier Ocean Wise study.“To visualize it, that’s the equivalent of 10 blue whales of microfibres entering our oceans, rivers and lakes every year.”Microplastics have been found in our food and water, although the impacts are not yet known. Graphic courtesy of Ocean Wise An @OceanWise report found microplastics can be significantly reduced by upgrading filters in washing machines. The new filters have the potential to catch up to 90 per cent of microfibres. #PlasticPollution The study of microplastics is still relatively new, says Hardman, who explains that further research needs to be done to explain what percentage of microfibres are released once garments are brought home versus during the production process, as well as the breadth of the effects on humans and animals.A 2019 University of Victoria study looked into the latter, and it found that people are consuming tens of thousands of plastic particles per year. Again, researchers say the full impacts need to be further analyzed, but that it’s an important step in understanding plastic pollution.Not only can microplastics be ingested, but they exist in the air and can be breathed in, explains lead author Kieran Cox.“Human reliance on plastic packaging and food-processing methods for major food groups, such as meats, fruits and veggies, is a growing problem. Our research suggests microplastics will continue to be found in the majority — if not all — of items intended for human consumption,” said Cox. “We need to reassess our reliance on synthetic materials and alter how we manage them to change our relationship with plastics.”So do corporations, says Hardman, who says clothing businesses can do things like design fleece (a main microfibre culprit) to have lower shed rates and create long-lasting garments.The report is part of the organization’s ongoing microfibre project, which sees collaborations between players in the clothing industry as well as government to work towards microplastic solutions, so she’s hopeful that more businesses will start to adopt suggested practices. Individuals can purchase long-lasting garments or secondhand items, rather than fast-fashion goods, which are more likely to shed microfibres. “It really energizes us to keep asking the challenging questions that are going to empower and enable businesses to take action and individuals to take action. We all have a part to play … it’s not just business, it’s not just policymakers, it’s not just consumers,” she said.“We are all part of the system. And we all have a role to play in tackling this very real problem, which is only going to grow if we don’t take action now.”

Why chemical pollution is turning into a third great planetary crisis

Thousands of synthetic substances have leaked into ecosystems everywhere, and we are only just beginning to realise the devastating consequences

Earth

21 July 2021

By Graham Lawton

Marcin Wolski

IT IS the 29th century and Earth is a dump. Humans fled centuries ago after rendering it uninhabitable through insatiable consumption. All that remains is detritus: waste mountains as far as the eye can see.

This is fiction – the setting for the 2008 Disney Pixar movie WALL-E. But it may come close to reality if we don’t clean up our act. “We all know the challenge that we’ve got,” says Mary Ryan at Imperial College London. “We can find toxic metals in the Himalayan peaks, plastic fibres in the deepest reaches of the ocean. Air pollution is killing more people than the current pandemic. The scale of this is enormous.”

Back when WALL-E was made, pollution and waste were near the top of the environmental agenda. At the 2002 Earth Summit in South Africa, global leaders agreed to minimise the environmental and health effects of chemical pollution, perhaps the most insidious and problematic category. They set a deadline of 2020 (spoiler alert: we missed it).

Recently, climate change and biodiversity loss have dominated environmental concerns, but earlier this year the UN quietly ushered pollution back to the top table. It issued a major report, Making Peace with Nature, declaring it a third great planetary emergency. “Do I think that is commensurate with the risk? Yes, I do,” says Ryan.

“It justifies being right up there at the top,” says Guy Woodward, also at Imperial. The key question, though, is what pollutants we should be worried about. “Many are innocuous. Some aren’t. Some interact in dangerous ways. That is what we need to grapple with,” says Woodward.

Pollution, the …

Coles bins Stikeez and minis for good following criticism of plastic promotions

Coles Coles bins Stikeez and minis for good following criticism of plastic promotions Environmental campaigners welcome announcement saying ‘the vast majority of the toys were either littered or dumped in landfill’ Lisa Cox Thu 22 Jul 2021 13.30 EDT Last modified on Thu 22 Jul 2021 13.31 EDT Coles has announced it will no longer …

Continue reading “Coles bins Stikeez and minis for good following criticism of plastic promotions”