Activists in Indonesia worried about plastic pollution wanted people to rethink their usage. So they built a museum made from more than 10,000 discarded bottles, bags, straws and single-use food packaging.The massive haul of items was fished out of local rivers and beaches that have become a dumping ground for such items, which pose a significant threat to marine life, ecosystems and communities around the world.The museum, which opened last month in the town of Gresik in East Java province, features thousands of plastic bottles that dangle overhead as visitors pass through the site, highlighting the sprawling impact of the marine crisis.While it is difficult to calculate precisely how much plastic has ended up in the world’s oceans, scientists have estimated that the yearly figure of waste being dumped could be as high as 12.7 million metric tons, according to data published in the journal Science.Plastics are virtually indestructible and while some items are biodegradable, it could take centuries for them to break down.Indonesia is among the world’s top contributors to plastic pollution, in a world where more than 8 million metric tons of plastic are dumped into oceans every year.It took activists from Indonesia’s Ecological Observation and Wetlands Conservation group three months to create the exhibit, which is known as “Terowongan 4444,” or “4444 tunnel.”Photos shared to the group’s official Facebook page in recent months highlight the extent of the plastic pollution problem. One image shows trash tangled in the low-hanging branches of trees lining riverbeds, while other images show activists bagging up countless sacks of debris.At the heart of the museum stands a statue of Dewi Sri, the goddess of prosperity, who is widely worshiped by the Javanese. The sculpture towers over visitors who are able to observe her skirt, which is made of discarded food and drink packaging — items that were bagged up by the group over the past few years.The group’s founder, Prigi Arisandi, told Reuters that the exhibition was built in a bid to spark change among people who may unwittingly be part of the problem.Wearing a T-shirt with a slogan that read, “I’m on a plastic diet,” Arisandi said he wanted visitors to become “educated” about the issue so they could help “reduce the use of single-use plastics.”“By looking at how much waste there is here, I feel sad,” one visitor told Reuters, while another told the agency he would be changing his consumer habits.“I will switch to a tote bag and when I buy a drink, I will use a tumbler,” Ahmad Zainuri said.Experts say that some initiatives to reduce individual plastic use, such as banning plastic straws, only have a minimal impact on plastic pollution — so wider efforts to ensure better waste collection and the use of recycled or biodegradable material are also essential.Along with the climate crisis, world leaders have also faced questions over the issue of plastic pollution, with advocacy groups calling on officials to do more to help struggling communities.Scientists have stressed that while it is paramount that officials take the issue of a warming climate seriously, the marine crisis should not be sidelined.“Climate change is undoubtedly one of the most critical global threats of our time,” Heather Koldewey of the Zoological Society of London told the BBC last month.“Plastic pollution is also having a global impact; from the top of Mount Everest to the deepest parts of our ocean,” she said, adding that both problems were intertwined and having a negative impact on ocean biodiversity.“It’s not a case of debating which issue is most important, it’s recognizing that the two crises are interconnected and require joint solutions,” Koldewey said.Read more:

Category Archives: Land

The US falls behind most of the world in plastic pollution legislation

In recent years, countries across the globe have implemented laws to mitigate plastic production and pollution. In the past two years, both large developed nations like Australia and smaller developing countries like Sri Lanka and Belize have passed ambitious national laws to phase out a number of plastic products like bags, cutlery, and straws.

But the U.S., a leading producer and consumer of plastics, remains woefully behind, even as it stands as one of the world’s biggest polluters. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the country produced 35.7 million tons of plastic waste in 2018, more than 90% of which was either landfilled or burned. The

U.S. ranks second in the world in total plastic waste generated per year, behind only China — though when measured per capita, the U.S. outpaces China. In 2019, the U.S. also opted not to join the United Nations’ updated Basel Convention, a legally binding agreement aimed at preventing and minimizing plastic waste generation that was signed by about 180 other countries.

More than 90 countries have established (or have imminent plans to establish) either bans or fees on single-use plastic bags or other products, according to data from the non-profit ocean conservation organization Oceana. The U.S. is not one of them. Though Americans have been aware of plastic pollution as an environmental concern as early as the mid-20th century, U.S. action against plastics has been piecemeal — the federal government has left it up to individual cities, counties, and states to decide whether and how to regulate plastics.

Related: Check out our Ocean Plastic Pollution guide

The plastic problem is growing increasingly urgent. More than

1 million plastic bags are used every minute, with an average “working life” of only 15 minutes. Experts believe the ocean will contain one ton of plastic for every three tons of fish by 2025 and, by 2050, more plastics than fish (by weight).

Not only does the ocean (and all life reliant on it) suffer from plastic pollution, but human health is also at risk. Microplastics have

well-documented impacts on human health, and have been found in 90% of bottled water and 83% of tap water. Our incessant plastic consumption is cultivated by “throwaway” culture, fueled by the plastic and oil and gas industries’ efforts to sustain high plastics consumption while distracting people with recycling campaigns.

This story is also available in Spanish

However, a new proposed federal bill—the

Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act—offers potential solutions, and could transform the U.S. from a hindrance to the global movement against plastics into a much-needed ally. Such federal action could help stop the fractured approach to tackling plastics in the U.S., and shift the burden from consumers to plastic manufacturers.

Advocates say even if the bill doesn’t pass in full, its component parts, especially those that are more bipartisan, could likely peel off and be recycled into other legislation. For example, a part of the bill addressing plastic pellets, or “nurdles,” has already broken off and become its own piece of potential legislation, the

Plastic Pellet Free Waters Act.

U.S. lags behind plastic pollution regulation

The European Union passed a comprehensive directive a couple of years ago. (Credit: campact/flickr)

Other countries not only produce less plastic than the U.S., but they’ve also more successfully legislated against plastic pollution. The European Union passed a comprehensive directive a couple of years ago, for example, that requires member countries to ban a slew of single-use plastic products, collect plastic bottles for recycling and reuse, and label disposable plastic products appropriately, at minimum. Many countries are going beyond those requirements.In Canada a federal ban on plastic bags, stir sticks, ringed beverage carriers, cutlery, straws, and food takeout containers made from hard-to-recycle plastics is set to take effect at the end of the year.It’s not just Western or “wealthier” nations who have successfully implemented measures against plastics. Dozens of countries across Africa, Asia, and Central and South America have legislation in place to quash the single-use plastic crisis.Christy Leavitt, the U.S. Plastic Campaign Director at Oceana, told EHN that the EU directive is just one example for the U.S. to emulate. Oceana has surveyed countries around the world, taking inventory of the global anti-plastic legislation and assessing where the U.S. sits comparatively, and found progressive policies in many pockets of the world.”Chile passed what is, if not the most comprehensive, one of the most comprehensive single-use plastic foodware policies in the world,” Leavitt said. Beyond banning single-use bags and straws, Chile prohibits all eating establishments from providing single-use cutlery or containers. Grocery and convenience stores must also display, sell, and take back refillable bottles, creating a cyclical system of bottle reuse.As early as 2002, the East African country Eritrea banned plastic bags in its capital city Asmara. The country implemented a nationwide ban on the import, production, sale, or distribution of plastic bags in 2005. Rwanda banned plastic bags in 2008 and then all single-use plastics in 2019, with heavy fines and even jail time for anyone found importing, producing, selling or using single-use plastic items.When countries across the globe with fewer resources than the U.S. successfully push out harmful plastic products, it gives the U.S. no excuse to be so behind, Leavitt added.

A fractured front on U.S. plastic pollution regulation

In the absence of national legislation in the U.S., local governments at the city, county, and state levels have regulated plastics. As a result, there is a diverse set of mandates and ordinances scattered across the country.

One paper in the Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning says that “as of August 2019, eight

U.S. states, 40 counties, and nearly 300 cities had adopted policies that, either through a ban, fee, or combination thereof, aim to reduce the consumption of single-use plastic bags.”

To Rachel Krause, a public administration researcher at the University of Kansas and author of the paper, it’s curious to see such a large issue relegated to local governments. “We tend to say that policy responses should be at scale or in proportion to policy problems,” she told EHN, “but local governments aren’t at scale with climate change, local governments aren’t at scale with global plastics. And yet, in a lot of places in the United States, that’s where we’re seeing the action happen.”

Local action against single-use plastic, by definition, has limited reach and is less efficient than sweeping national policy would be. Ordinances at a city or county level are also prone to being struck down by statewide preemption laws, when states ban local governments from taking action.

Eighteen states have some sort of preemption law in place. In Texas, for example, individual cities like Laredo tried to implement plastic bag bans, but the Texas Supreme Court knocked them down in 2018, saying they conflicted with state solid waste management laws.

That said, “the amount of just individual pieces of legislation that have been introduced at the state and local level, in the last five years has, increased by an order of magnitude, maybe more,” Alex Truelove, the Zero Waste Campaign Director with U.S. Public Interest Research Group (PIRG), told EHN. The legislative landscape felt so much more sparse just a few years ago, Truelove added — a great sign, since the more states engaging in anti-plastics discourse, the harder the issue is to ignore on a national level. Plus, “every time something passes, we learn something” about what does and does not work.

The problem is “it’s much easier to block something than to get something passed,” University of Southern Maine environmental policy researcher Travis Wagner told EHN. This is especially true at the federal level. He added that the federal government explored possible legislation against plastics as far back as the 1970s, as bottle bills were adopted around the country.

“Bottle bills,” also known as “container deposit laws,” typically work by mandating small deposits on drink containers like plastic bottles and metal cans that customers can get back if they recycle those bottles. Oregon passed the first bottle bill in the U.S. in 1971, and by 1986, 10 states had enacted some kind of bottle bill into law (there are still only 10 states doing this to date). In the 1970s, Wagner said, it seemed like there was enough momentum to pass a national bottle bill, “but politically, it was just really, extremely difficult.”

In the half century since the federal government first considered taking a national stance on plastics, the issue has only gotten worse.

Individuals get blamed as plastic production skyrockets

Historically, the conversation around plastic pollution in the U.S. has centered on individuals’ and communities’ abilities to recycle. (Credit: Brian Yurasits/Unsplash)

Historically, the conversation around plastic pollution in the U.S. has centered on individuals’ and communities’ abilities to recycle. But Leavitt said that recycling was an ideal pushed on the public by the plastics industry as “a way for [them] to put the blame of plastic pollution and the responsibility to fix it on consumers. And it worked. While we focused on recycling, industry exponentially increased the amount of plastic it produced.”The idea that it is the individual’s responsibility to recycle, to not litter, and to buy less was so pervasive “that it’s become embedded in our psyche,” added Wagner. “That’s the industry saying ‘It’s not us, it’s you.'”Meanwhile, records and reports from as early as 1973 suggest top industry executives knew that plastic recycling could never be successful on a large scale.”It’s all coming down to dollars and cents for the industry,” Shannon Smith, Manager of Communications and Development for the nonprofit FracTracker Alliance, told EHN. “The misperception is that there’s a demand for all of this plastic, and so the industry is just responding to the demand of consumers, where it’s really the opposite.” In reality, she added, there’s an oversupply of fracked gas in the U.S., and one of the best ways to profit from all that supply is to generate more demand for plastic. “So it’s totally industry driven.”Plastics are primarily made from the natural gas byproducts ethane and propane, which are turned into plastic polymers in high-heat facilities in a process known as “cracking.” The U.S. is the world’s leading producer of natural gas, with 30 cracker plants currently in operation and at least three more expected by mid-2022. To add insult to injury, Smith said, “the fracking industry has never been profitable,” and petrochemical companies and facilities are actually the frequent recipients of government subsidies. “We’re subsidizing them, we’re paying for their ability to make a profit while they’re sacrificing our health.”It’s time to put the responsibility of managing plastic waste back on the companies producing it, Truelove said. “If f your bathtub is overflowing, the first thing you do is turn off the tap,” he added.

Break Free From Plastic Pollution

Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR), pictured here, and Representative Alan Lowenthal (D-CA), introduced the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act. (Credit: merkley.senate.gov/)

A new piece of federal legislation seeks to turn off the proverbial tap. First introduced in 2020 and reintroduced in March 2021 by Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Representative Alan Lowenthal (D-CA), the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act, if passed, would comprehensively address plastic production, consumption, and waste management in the country.”The idea behind the bill was to really kind of assemble all of the best ideas from not just around the country, but honestly from around the world,” said Truelove. The EU directive, for example, was a great precedent and a beacon for the direction the U.S. could follow, he added.Congressman Lowenthal wrote to EHN that “this bill incorporates best practices and important common-sense policies. While it may be ambitious – it is by no means radical.” The bill would ban single-use plastic bags and other non-recyclable products, include a bottle bill, and channel investments to recycling and composting infrastructure. “The legislation makes producers responsible for the end use of their own products,” added Congressman Lowenthal. Producers of plastic packaging would be required to design and finance waste and recycling programs.Truelove also mentioned that the bill, importantly, sets a minimum for states to abide by, allowing individual local governments to pursue or keep more aggressive policies —”we don’t want to punish the states that have those stronger laws.”The proposed bill also includes components of environmental justice, requiring the EPA and other agencies to more rigorously study the cumulative environmental and health impacts of incinerators and petrochemical plants, while also placing a moratorium on new or expanding facilities. Frontline and fenceline communities — so named because they are situated next to these industrial plants, right up to the fences — are the most harmed by the poor air and water quality inflicted by the plastics industry. They are also disproportionately communities of color.

The future of plastics regulation

The Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act has not been put into law yet. It is currently co-sponsored by 12 other senators, but the timeline for when it might be passed is still very unclear.Truelove is hesitant to make predictions, but he’s optimistic that, in the long run, some form of federal legislation will pass. Wagner is more skeptical: “I am optimistic, but not at the national level.” In his mind, individual states will continue to lead.Though the full Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act has no clear path forward t at the moment, pieces of the bill are already breaking off and being discussed more seriously. Lowenthal wrote that breaking off elements of the bill and integrating them with more narrowly focused legislation with bipartisan support, or attaching them to bills at the verge of being passed, is a practical move to get parts of the bill through Congress bit by bit. “A lot of this work tends to be incremental. It almost has to be, by nature, just the way our institutions are built,” said Truelove.But even if the bill is passed, it’s still no panacea. The plastics and petrochemical industries will likely continue pushing for what Truelove calls “false solutions,” like chemical recycling innovations (where plastics are broken down again into polymers, effectively turning them into diesel fuel — a different environmental nightmare) or flashier anti-littering campaigns.”What we’re doing is an affront to [industry’s] business model,” he added. “You’ve got Dow, DuPont, Chevron, Exxon, and so on…and they’re incredibly powerful organizations with a lot of political influence.” To substantially move towards less plastic production and more reusable products, the government will need to push past those distracting pseudo-solutions, even when they seem like they could be profitable.”It’s totally doable,” said Truelove. “I mean, I think if we can get to the moon, we can figure out how to make it easy for people that have reusable foodware or reusable packaging for shipping.”Banner photo credit: Naja Bertolt Jensen/Unsplash

Research reveals how much plastic debris is currently floating in the Mediterranean Sea

Credit: Unsplash/CC0 Public Domain

A team of researchers have developed a model to track the pathways and fate of plastic debris from land-based sources in the Mediterranean Sea. They show that plastic debris can be observed across the Mediterranean, from beaches and surface waters to seafloors, and estimate that around 3,760 metric tons of plastics are currently floating in the Mediterranean.

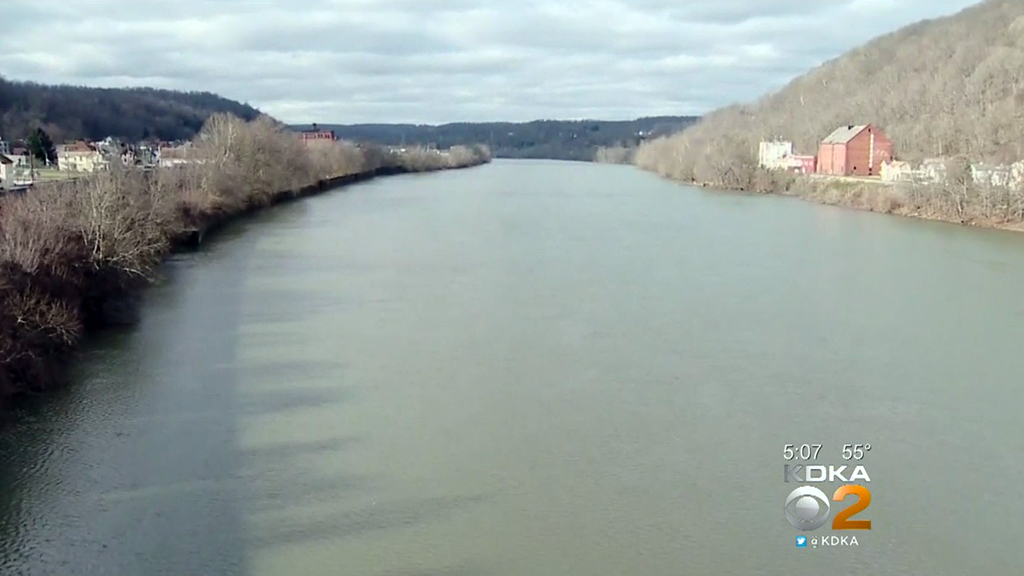

PennEnvironment study: Tested waterways in Pennsylvania contaminated with microplastics

PITTSBURGH (KDKA) — Plastic bags are everywhere, including our homes and stores.The deputy director of PennEnvironment said they are also in our water and on our streets. The organization tested 53 popular waterways in the state, including Pittsburgh’s three rivers, and found the waterways are contaminated with microplastics, which are pieces of plastic smaller than a grain of rice.READ MORE: 4 Men Facing Charges Connected To “Grandparent Bond Scams” In Allegheny And Westmoreland Counties“Often, these tiny pieces of plastic contain chemicals linked to cancer and hormone disruption,” said deputy director Ashleigh Deemer. “They can be in our drinking water sources and they can be taken up by fish and later consumed by us.”Deemer said people consume about a credit card’s worth of plastic each week. She added that plastic bags also cause a litter problem and negatively impact climate change.“Without changing course, we know that emissions from plastic production and incineration could amount to 56 gigatons of carbon between now and 2050,” Deemer said. “That’s almost 50 times the annual emissions of all the coal-fired power plants in the U.S.”Deemer said one of the best ways to save people and the planet is to ban plastic bags. More than 100 organizations and business owners signed a letter to show their support.The owner of City Books is one of the supporters.READ MORE: Fall Fun: 2021 Guide To Festivals, Farms And Haunts In Western Pa.“I think that paper bags keep our business model itself sustainable, and then we’re able to pay that forward in terms of the environment and our customers,” owner Arlan Hess said.Deemer said they’re urging Pittsburgh City Council members to ban plastic bags.“We estimate this policy has the potential to prevent 108 million plastic bags from entering our waste stream and environment each year,” Deemer said.Local residents KDKA spoke to support the idea.“I’ll use a plastic bag for kitty litter, but I can also use a paper bag for that as well,” Shadyside resident Franc Grigore said.MORE NEWS: With Expanded And New Programs, Democrats Say Human Infrastructure Bill Will Rebuild American Middle ClassCouncilmember Erika Strassburger said she has been working on legislation to ban plastic bags for months. She plans to introduce a bill this fall.

You do know that, in most cases, bottled water is just tap water?

Since the start of the pandemic, thirsty Americans have drowned their sorrow in bottled water.Even before the coronavirus blew into all our lives, bottled water was, and has been for years, the No. 1 beverage in the United States, surpassing soft drinks as the choice of increasingly health-conscious consumers.The COVID-19 pandemic only accelerated things.According to a recent report from the International Bottled Water Assn., sales of bottled water exploded last year “as consumers stocked up in order to stay home amid the coronavirus crisis.”

“Per-capita consumption of bottled water reached another all-time high,” it said.Gary Hemphill, managing director of research for the consulting firm Beverage Marketing Corp., told me bottled water sales are projected to be even higher this year.“Bottled water’s success is driven by its healthful image and positioning as a beverage to be consumed virtually any time and anywhere,” he said.Call this a triumph of perception over reality.

Business

Column: If you’re a coffee drinker, you really need to care about climate change

Coffee prices, and food costs in general, are rising because of climate change. For consumers, that’s a good reason to take this problem seriously.

The first thing you need to know is that, for most Americans, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with your tap water.The second thing you should know is that the market leaders for bottled water — Coke and Pepsi — are just filtering and bottling tap water, and then selling it at a big markup.And perhaps most important of all, bottled water is no friend to the environment.

According to the Container Recycling Institute, Americans throw away more than 60 million plastic water bottles every day. Most end up in landfills, gutters and waterways.“If your tap water is potable, which is the case for most big cities in America, you don’t need bottled water,” said Barry Popkin, a professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.“There’s an aura of greater safety around bottled water,” he told me. “That’s just not valid.”I heard the same from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which serves municipalities and water districts throughout the region.

Paul Rochelle, the agency’s water quality manager, said almost a quarter-million tests are performed annually on the local water supply to ensure safety.“Not only is our water safe, it tastes great,” he said. “Metropolitan has three times won best-tasting tap water in the nation, including this past year.”

Business

Ever wonder where your drinking water comes from? A reader asked and we answer

L.A. pumps its local groundwater, but other water sources are important for replenishing the supply.

Global bottled water sales hit nearly $218 billion last year, according to Grand View Research. Sales are expected to rise by 11% a year through 2028.

“Rising consumer consciousness towards the health benefits of consuming bottled water is projected to drive market growth over the forecast period,” the research firm said.Those health benefits, however, are questionable.“To my knowledge, there is no published evidence to suggest that bottled water is either healthier or safer than tap water — none whatsoever,” said Dan Heil, a professor of exercise physiology at Montana State University.“In fact,” he told me, “there is published evidence to suggest exactly the opposite.”

Business

Column: Adding dental coverage to Medicare makes a lot of sense — except to dentists

Democrats are again trying to bring dental coverage to Medicare. Dentists, fearing lower payments, are against the idea.

Heil said that when tap water is filtered for bottling, the process removes beneficial minerals such as calcium and magnesium. The bottled water industry considers these minerals “impurities,” he said.“While stripping the impurities from tap water does, in fact, provide a nearly pure form of water, that fact does not support the premise that pure water is healthier or better for the body than tap water with naturally occurring minerals,” Heil observed.The leading bottled water brands are nothing more than municipal tap water that’s been run through a filter. This is what Coca-Cola does with its Dasani water. Pepsi does the same with its Aquafina brand.

“Bottled water is tap water,” said Marion Nestle, a highly regarded professor emeritus of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University.“Companies buy water from municipal supplies at very low cost and sell it back to the public at a huge markup,” she told me. “I am not aware of any evidence that bottled water is safer than city water in places where cities take care of their water.”Some cities may not do that so well; Flint, Mich., comes to mind. But, as Popkin noted, most big cities do a good job of maintaining safe drinking water.In 2012, California wrote into the state Constitution that safe drinking water is a human right. Although the tap water in most California cities passes muster, some rural areas still face challenges.

California

A 7.1 earthquake couldn’t kill this Mojave Desert town. But a water war just might

The small desert town of Trona imports its water from 30 miles away. A 2014 law aimed at preserving California’s groundwater has set off a complicated battle that has some residents fearing the worst.

The problem is most acute in the Central Valley, where large farms have contaminated water supplies with agricultural chemicals. The state passed a law in 2019 allocating $130 million a year to improve that situation.If you’re among the vast majority of Californians with access to safe drinking water, all you’re doing any time you purchase bottled water is enriching the conglomerates that, unlike you, simply turned the faucet.“Unfortunately, many people spend their hard-earned money paying for bottled water rather than using their own tap water,” said Walter C. Willett, a professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard University. “This rarely makes sense.”

Yes, bottled water is convenient. But it’s really not that difficult to fill a reusable bottle before you leave home. You’ll save money and, in most cases, won’t cut corners on safety.For extra peace of mind, look into one of the many filtration systems available for home use. Prices start around $20.And let’s hammer this point home: Bottled water is really bad for the environment.A recent study out of Europe found that the impact of bottled water on natural resources, including the millions of barrels of oil needed to manufacture all those plastic bottles, is 3,500 times higher than for tap water.

And seeing as your bottled water probably came from municipal pipes anyway, you’re being played for a chump by the roughly $200-billion U.S. beverage industry.Cheers!

Climate Change: Don't sideline plastic problem, nations urged

Getty ImagesScientists are warning politicians immersed in climate change policy not to forget that the world is also in the midst of a plastic waste crisis. They fear that so much energy is being expended on emissions policy that tackling plastic pollution will be sidelined. A paper from the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Bangor University says plastic pollution and climate change are not separate.It says the issues are actually intertwined – and each makes the other worse. Manufacturing plastic items adds to greenhouse gas emissions, while extreme weather such as floods and typhoons associated with a heating planet will disperse and worsen plastic pollution in the sea.The researchers highlight that marine species and ecosystems, such as coral reefs, are taking a double hit from both problems. Hermit crabs mistake plastic pollution for foodPlastic from take-out food is polluting the oceansUK criticised for dumping plastic waste in TurkeyGetty ImagesReefs and other vulnerable habitats are also suffering from the seas heating, from ocean acidification, pollution from farms and industry, dredging, development, tourism and over-fishing. And in addition, sea ice is a major trap for microplastics, which will be released into the ocean as the ice melts due to warming. The researchers want politicians to address all these issues – and not to allow climate change to take all the policy “bandwidth”.Professor Heather Koldewey from ZSL said: “Climate change is undoubtedly one of the most critical global threats of our time. Plastic pollution is also having a global impact; from the top of Mount Everest to the deepest parts of our ocean. “Both are having a detrimental effect on ocean biodiversity; with climate change heating ocean temperatures and bleaching coral reefs, to plastic damaging habitats and causing fatalities among marine species. “The compounding impact of both crises just exacerbates the problem. It’s not a case of debating which issue is most important, it’s recognising that the two crises are interconnected and require joint solutions.” Professor Koldewey added: “The biggest shift will be moving away from wasteful single-use plastic and from a linear to circular economy that reduces the demand for damaging fossil fuels.” Helen Ford, from Bangor University, who led the study, said: “I have seen how even the most remote coral reefs are experiencing widespread coral death through global warming-caused mass bleaching. Plastic pollution is yet another threat to these stressed ecosystems. “Our study shows that changes are already occurring from both plastic pollution and climate change that are affecting marine organisms across marine ecosystems and food webs, from the smallest plankton to the largest whale.” ZSL is urging world governments and policy makers to put nature at the heart of all decision making in order to jointly tackle the combined global threats of climate change and biodiversity loss.Follow Roger on Twitter @rharrabin

This fjord shows even small populations create giant microfiber pollution

Researchers found that one tiny Arctic village’s unfiltered sewage produces as much microplastic as the treated waste of more than a million people.Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago chilling halfway between the Nordic country and the North Pole, is known as much for its rugged beauty as its remoteness. From the village of Longyearbyen, visitors and roughly 2,400 residents can appreciate the stark terrain around the fjord known as Adventfjorden.But the beauty of this Arctic inlet conceals messier, microscopic secrets.“People see this nice, clean, white landscape,” said Claudia Halsband, a marine ecologist in Tromso, Norway, “but that’s only part of the story.”The fjord has a sizable problem with subtle trash — namely microfibers, a squiggly subset of microplastics that slough off synthetic fabrics. Microfibers are turning up everywhere, and among researchers, there’s growing recognition that sewage is helping to spread them, said Peter S. Ross, an ocean pollution scientist who has studied the plastic fouling the Arctic. While the precise impact of microfibers building up in ecosystems remains a topic of debate, tiny Longyearbyen expels an extraordinary amount of them in its sewage: A new study shows that the village of thousands emits roughly as many as all the microplastics emitted by a wastewater treatment plant near Vancouver that serves around 1.3 million people.The findings, published this summer in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Science, highlight the hidden impacts that Arctic communities can have on surrounding waters, as well as the major microfiber emissions that can be produced by even small populations through untreated sewage.Adventfjorden’s microfibers arrive through a submerged pipe that juts into the fjord like an arm bent at the elbow. It spits out the community’s untreated sewage — urine and feces, plus mush pushed down kitchen sinks and suds from showers and washing machines. Around the world, small or isolated communities wrangle sewage in numerous ways, from corralling it in septic tanks to relying on composting latrines. In Longyearbyen, waste mingles in a single pumping station no bigger than an outhouse before squelching to the fjord through tubes winding atop the frozen earth.“People think, Out of sight, out of mind; the ocean will take care of it, but this stuff piles up,” Dr. Halsband said.Microscopes helped researchers make sense of the tiny trash they’d scooped from the pumping station, and estimate how many of the microfibers, shown here, might be spilling into the fjord.Maria JensenCurious about trash that isn’t immediately visible to the naked eye, Dr. Halsband and four collaborators sampled the wastewater for microfibers over one week each in June and September 2017, then modeled how the tiny bits might float around the fjord.“It wasn’t as smelly as we were afraid it would be, but there were floaters,” said Dorte Herzke, a chemist at the Norwegian Institute for Air Research and the lead author of the paper.Back in the lab, researchers filtered and sorted the samples. Lacking equipment that could identify fibers as synthetic or organic, the team discarded anything clear or white that might be cellulose. Still, scores of pieces remained, including dark colors likely from outdoor gear — especially in the September samples, collected “when the hunters start to emerge” and bundle up, Dr. Herzke said. (Previous research found that outerwear such as synthetic fleece tends to shed microfibers in washing machines.)From these counts, the researchers estimated that the community flushes at least 18 billion microfibers into the fjord each year — roughly 7.5 million per person.To start puzzling out what happens to the bits in Adventfjorden, the team modeled where the microfibers could accumulate and which species might encounter them. The researchers calculated that the lightest microfibers would stay suspended near the surface and leave the fjord within days, dispersing in roomier waters. Heavier ones would sink to the bottom or cluster near the sewage pipe or inner shore, places that are habitats for plankton, bivalves and bloody-red worms.Deonie and Steve Allen, married microplastics researchers at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland and Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, praised the paper’s model and said in an email that its “really local and timely field data and sampling” bolster its results. But they said it would benefit from chemical analysis, too, a sentiment echoed by Sonja Ehlers, a microplastics researcher at the University of Koblenz-Landau in Germany. Ms. Ehlers said she would also like to see the team document how local creatures are interacting with the microfibers.Dr. Halsband suspects they might be consuming the castoffs. “We know they don’t discriminate against plastic,” she said, adding that the team is also keen to learn whether fibers can snarl planktons’ appendages and interfere with their drifting.Dorte Herzke, documenting walruses with Longyearbyen in background.Louise Kiel JensenThe researchers returned to the fjord this past summer, collecting samples to check the model’s predictions. Those samples are in a freezer, and will be subjected to a chemical analysis.The scientists hope their work will prompt Arctic communities to mull new ways to manage sewage and the trash that hitchhikes through it.“Norway has a lot of fjords,” Dr. Herzke said, and Adventfjorden surely isn’t the only one flecked with feces and tiny pieces of trash. That makes it a useful case study. “Once we understand this one,” Dr. Herzke added, “we can understand others.”Where thorough sewage treatment isn’t feasible, Dr. Halsband said, communities could consider basic filtration, promote wool alternatives to synthetics and eke out more wears between washes.As for Longyearbyen, the researchers said it will soon introduce filtration to capture large debris. That may intercept some smaller bits, too — maybe even downright teeny ones.

Industrial plastic is spilling into Great Lakes, and no one's regulating it, experts warn

As the people of Toronto flocked to the Lake Ontario waterfront to swim, paddle and generally escape pandemic isolation, Chelsea Rochman’s students at the University of Toronto were throwing plastic bottles with GPS trackers into the water.The research team’s goal is to track trash that ends up in the lake, to figure out where it accumulates in the water and where it’s coming from in the first place. Using information from the tracking bottles, they chose spots to put in Seabins — stationary cleaning machines that suck in water all day and trap any garbage and debris — at marinas along the waterfront. They are emptied daily, and the debris collected in them is examined to ferret out what kinds of trash is getting into the lake. Chelsea Rochman, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, and her team have been analyzing plastic waste being collected by Seabins placed in the Toronto harbour.

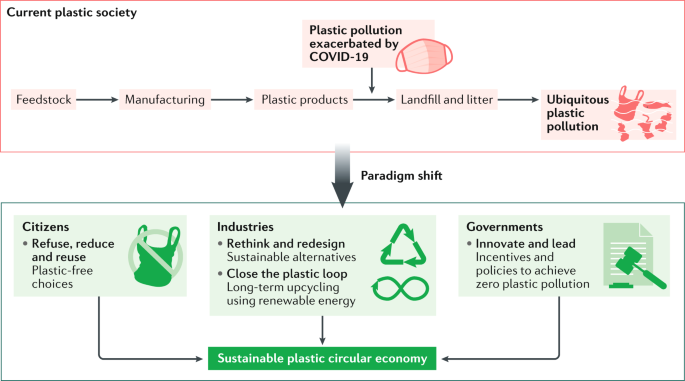

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitates a shift to a plastic circular economy

The COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating plastic pollution. A shift in waste management practices is thus urgently needed to close the plastic loop, requiring governments, researchers and industries working towards intelligent design and sustainable upcycling.

Plastic pollution is ubiquitous. As of 2015, approximately 6,300 million metric tons (Mt) of plastic waste had been generated globally1, motivating myriad initiatives to reduce plastic consumption. However, the focus on plastic waste reduction has since been overshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Traditionally minor sources of plastic pollution — including personal protective equipment (PPE) — have become far more prominent, exacerbating consumption. Moreover, some regulatory measures meant to reduce plastic have been delayed and/or rolled back during the pandemic, stalling or even reversing the longstanding global battle to mitigate plastic pollution.Approximately 400 Mt of plastic waste was produced globally in 2019 (ref.1). However, the estimated waste volume reached over 530 Mt in the first 7 months of the COVID-19 outbreak (December 2019–June 2020) (ref.2), suggesting plastic waste totals for 2020 would be at least double those of 2019. Part of this increase results from the public demand for disposable face masks and gloves; globally, an estimated ~3.4 billion protective face masks were discarded daily from December 2019 to June 2020 (ref.2). Moreover, the consumption of plastic packaging by takeaway services, e-commerce outlets and express delivery industries increased extensively with social distancing requirements. Takeaway and home delivery services generated additional 1.21 Mt of plastic waste from April to May 2020 during the lockdown in Singapore alone.A notable portion of this waste does not make it to municipal waste streams. Masks, gloves and other plastics (including hand sanitizer bottles) are found indiscriminately littered and disposed of without precautionary measures. Such inadequate plastic waste management results in an alarming accumulation of plastic in soil and aquatic ecosystems. For example, it is estimated that approximately 1.56 billion face masks (~5.66 Mt of plastic) ended up in the oceans in 2020. Large pieces of plastic waste, (including masks,) can break into microplastics ( >100 nm and

Plastics industry lashes out at 'regressive' Democratic tax plan

A Democratic proposal to help finance the party’s $3.5 trillion spending bill by taxing single-use plastics is generating sharp pushback from members of the industry, who argue it would produce more waste and hurt average Americans.The Senate Finance Committee is weighing the idea of a tax on the sale of virgin plastic resin — the base materials used to make single-use plastics — as one potential way to pay for the mammoth spending bill, according to a document released earlier this month.But the proposal has garnered fierce opposition from the plastics division of the American Chemistry Council (ACC), a trade group representing 28 companies including oil giants such as ExxonMobil, Chevron and Shell as well as major chemical manufacturers such as DuPont and Dow Chemical.ADVERTISEMENTThe group argues that such a levy would amount to some $40 billion in additional taxes and “punish Americans” who depend on plastics in electric vehicles, home insulation, electronics and packaging, while funding unrelated government programs and fueling inflation.“Plastic goes into a variety of applications, not just food packaging,” Joshua Baca, vice president of the ACC’s plastics division, told The Hill. “At the end of the day, this would result in a regressive tax that would largely impact those who can least afford it.”Baca argued that implementation of the measure would lead to “incentivizing the use of other materials — whether that’s paper, glass, aluminum — all of which have a higher [carbon] footprint than plastics.”Manufacturing such alternatives produces 2.7 times more greenhouse emissions than their plastic counterparts and consumes twice as much energy, Baca contended.If all plastic bottles were replaced by glass ones, the power necessary to manufacture them would be the equivalent to running 22 large coal fired power plants, he said, arguing that such a shift would negatively impact the climate and “also be detrimental to our economy.” A plastic resin tax is not the only funding option under consideration for the $3.5 trillion spending bill. The Senate Finance Committee is also discussing taxes on stock buybacks and on corporations whose CEO pay exceeds the pay of their average workers, as well as energy-tax proposals.ADVERTISEMENTThe idea for a plastics tax was first introduced by Sen. Sheldon WhitehouseSheldon WhitehouseDemocrats draw red lines in spending fight What Republicans should demand in exchange for raising the debt ceiling Climate hawks pressure Biden to replace Fed chair MORE (D-R.I.) in August. His bill, known as the REDUCE Act, would impose a 20-cent per pound fee on the sale of new plastic for single-use producers — with the goal of helping “recycled plastics compete with virgin plastics on more equal footing,” according to Whitehouse’s office.“Plastic pollution chokes our oceans, hastens climate change, and threatens people’s well-being,” Whitehouse said last month. “On its own, the plastics industry has done far too little to address the damage its products cause, so this bill gives the market a stronger incentive toward less plastic waste and more recycled plastic.” This “excise tax” — a duty imposed on a specific good — would apply to virgin resin, according to Whitehouse’s bill. Manufacturers, producers and importers of the resin would pay $0.10 per pound in 2022, which would gradually rise to $0.20 per pound in 2024.The fees generated by this process would go toward a Plastic Waste Reduction Fund, which would serve to improve recycling activities. The ACC immediately opposed the REDUCE Act in August, arguing that policymakers should instead adopt comprehensive policies that could lead to a “circular economy” — an economy in which production and consumption focuses on extending the lifecycle of products and minimizing waste, as defined by the European Union.Some policies the ACC has backed include requiring plastic packaging to contain 30 percent recycled plastic by 2030, developing a national recycling standard for plastics and studying the impact of greenhouse gases from materials, among other proposals.Baca stressed the importance of establishing a better set of recycling standards for communities across the country, arguing that suitable regulations for recycling technologies would ensure “that private sector investment continues to happen at a commercial scale.”“When you tie all of those things together, that is how you get a circular system,” Baca said. The need to transition domestic recycling programs to a “circular economy” was the topic of discussion at a Senate Environment and Public Works Committee hearing on Wednesday. “I love the idea of a circular economy, where things — and the materials they are made of — can be reused over and over again instead of ending up in a landfill somewhere,” Committee Chairman Tom CarperThomas (Tom) Richard CarperOvernight Energy & Environment — Presented by the League of Conservation Voters — EPA finalizing rule cutting HFCs EPA finalizes rule cutting use of potent greenhouse gas used in refrigeration The Hill’s Morning Report – Presented by AT&T – US speeds evacuations as thousands of Americans remain in Afghanistan MORE (D-Del.) said at the hearing.Carper called upon companies to “step up and take greater responsibility for reducing, reusing and recycling their products,” adding that the government should play a role in ensuring that industry can succeed in this effort.In response to the hearing, Baca said that the ACC submitted statements expressing the group’s viewpoints, including measures it would support.ADVERTISEMENTAsked how the group’s members are working to make hard plastics easier to recycle, Baca explained that traditional recycling tools have their limitations and more advanced systems must be developed to break down plastics into their basic building blocks.Tennessee-based Eastman Chemical has invested in a $150 million plastics facility that will come online soon, he said, adding that ExxonMobil has partnered with Oregon-based Agilyx to launch a joint plastic recycling venture.Baca also said that due to supply chain issues, plastic manufacturers cannot all overhaul their plants to use solely recycled or biobased feedstock. To use more recycled plastic, companies need to either have the innovative technologies to break down hard-to-recycle materials or the means to collect feedstock, he said.To date, Baca said, the plastics industry has invested almost $7 billion in promoting advanced recycling technologies, which he called “a step in the right direction,” as many companies begin to launch these technologies on a commercial scale.“Brands have made a commitment to use more recycled plastics,” Baca said. “If we don’t produce and make that material we won’t be in business. This is not only good for our company, bottom line, but it’s good for the environment.”