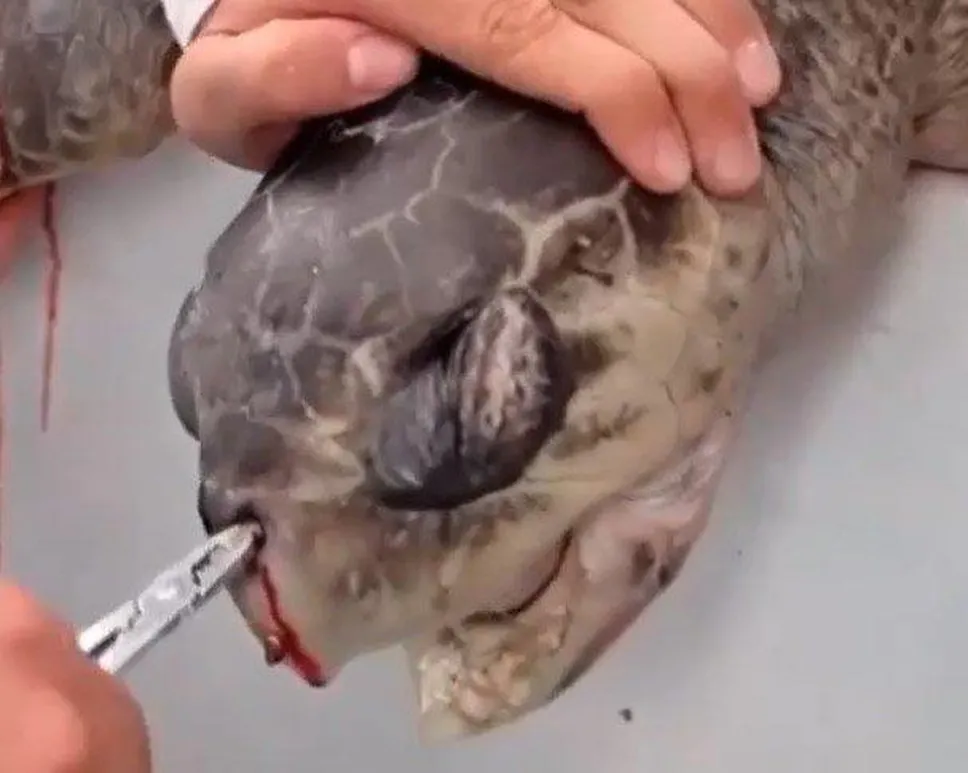

WATERLOO REGION — When Rebecca McIntosh of Kitchener signed up for the zero waste challenge, the married mother of two found “sneaky plastics” among the garbage she never thought about before.McIntosh didn’t know it, but she had been “wishcycling” — assuming a container or bag could be recycled, so it was tossed into the blue box.But during the zero waste challenge, she scrutinized every piece of garbage her family produced. The five-day challenge, run by the Kitchener charity Reep Green Solutions, is to have each member of the household produce no more waste than what a single Mason jar can hold.“We think we lead a low-waste lifestyle, but until you pay attention you don’t really know where all your waste comes from,” said McIntosh.She long believed ice cream containers could be recycled. Wrong: they contain plastic between the cardboard-like layers and are not recyclable. Cardboard alone and most plastics on their own can be recycled, but not when combined into a single product. “That was eye-opening,” said McIntosh.McIntosh and her family have done the challenge twice. The real benefit is looking closely at the garbage produced, and thinking about ways to reduce it.“We made changes afterwards,” said McIntosh. “Now we buy ice cream in a full, plastic container that is recyclable, or a glass one.”The UN Environment Assembly voted in March 2022 to end plastic pollution, and forge an international legally binding agreement by the end of 2024.When Canada was chairing the G7 group of advanced economies in 2018, it called for reducing the use of plastic. It spent years developing new regulations.Ottawa’s first phase of a multi-year program to eliminate plastics came into effect about a month ago with a ban on importing or manufacturing six plastic items: plastic checkout bags, cutlery, stir sticks, straight straws, chopsticks and takeout containers. Businesses have until Dec. 20, 2023, to use up existing inventories and start using replacements.Beginning in June, plastic ring carriers can no longer be made or imported into Canada. Businesses have a year to use up existing supplies, but beginning in June 2024, ring carriers will be banned.The government will also prohibit the export of plastics in the six categories by the end of 2025, making Canada the first among peer countries to do so internationally, says a federal government statement.The video “The Story of the Sea Turtle with the Straw” inspired millions of people to stop using plastic straws.screen shot from the viral video: The story of the sea turtle with straw in it’s nostril.Over the next decade, the world-leading ban will eliminate an estimated 1.3 million tonnes of hard-to-recycle plastic waste and more than 22,000 tonnes of plastic pollution, which is equivalent to over a million garbage bags full of litter, says the statement.But if you don’t eat fast food, the federal ban will have little impact.“We don’t drink bottled water, we don’t use plastic straws, the single-use plastics are not something we had a lot of in our lives anyway,” said McIntosh.For McIntosh and her family, “sneaky plastics” are the problem.“It was more the hidden plastics, the ice cream container with plastic layers, or even meat packaging you think is a paper material but it is actually plastic, so it’s garbage,” said McIntosh.Plastics pollution is so widespread, microscopic plastics are showing up in human blood, poop and placenta.But Jennifer Lynes Murray, a University of Waterloo professor who teaches business and environment, social marketing and enterprise strategies for social accountability, has worked for more than a decade on one of biggest generators of single-use plastic waste — concerts, sporting events and festivals.For a decade Murry worked with artists and musicians, venues and promoters to ban the use of plastic cups at venues. Instead, the fans can bring refillable containers, and free water is provided at filling stations. The Hillside Festival in Guelph has adopted many green initiatives, said Murray.The federal government successfully battled other, huge environmental challenges.In the 1980s Ottawa negotiated an acid rain reduction treaty with the U.S. that reversed the acidification of many lakes in Ontario and Quebec.In the 1970s an international treaty was approved in Montreal to eliminate chlorofluorocarbons from aerosol sprays. The harmful chemicals caused huge holes in the ozone layer. As a result, the holes are shrinking and will be closed entirely in about 20 years.The same thing can happen with plastics, said Murray.“We lived without plastics prior to the 1950s, so there are definitely ways we can live without them again,” said Murray.“It is a three-pronged challenge — how willing are people to make the changes, how available are the alternatives and how will the government encourage that through policies and regulations?” said Murray.She watched a single image galvanize the public — a sea turtle with a straw stuck in its nose. The 2015 pictures and video showed researchers removing a plastic straw that was embedded in the turtle’s nostril.“It created this whole movement, and within a year nobody was using plastic straws and it was really widespread as well,” said Murray. “When you get the momentum, things can happen quickly.”Canada needs to ban a lot more plastics than the six items associated with takeout food, and it needs to act more quickly, said Sarah King, the Vancouver-based head of the Oceans and Plastics Campaign for Greenpeace.“The current ban covers less than three per cent of the plastic waste we generate in Canada,” said King.The blue box program is as widely loved as it is deeply flawed, she said, and only encourages and enables more widespread use of plastics.“Recycling we know is not the solution to the plastic waste and pollution crisis,” said King. “This whole idea of plastic recycling is a myth. because many people across this country have come to learn that less than nine per cent of plastic is recycled in Canada.”King said PVC, the black plastic pipe, should also be banned. Polystyrene — a white, spongy material widely used for coffee cups and clamshell takeout containers — should be banned as well, she said.Polystyrene “is highly polluting in its production. And due to the nature of the material, when it ends up in the environment it breaks apart very easily and spreads,” said King.SHARE:

Category Archives: Plastic Pollution Articles & News

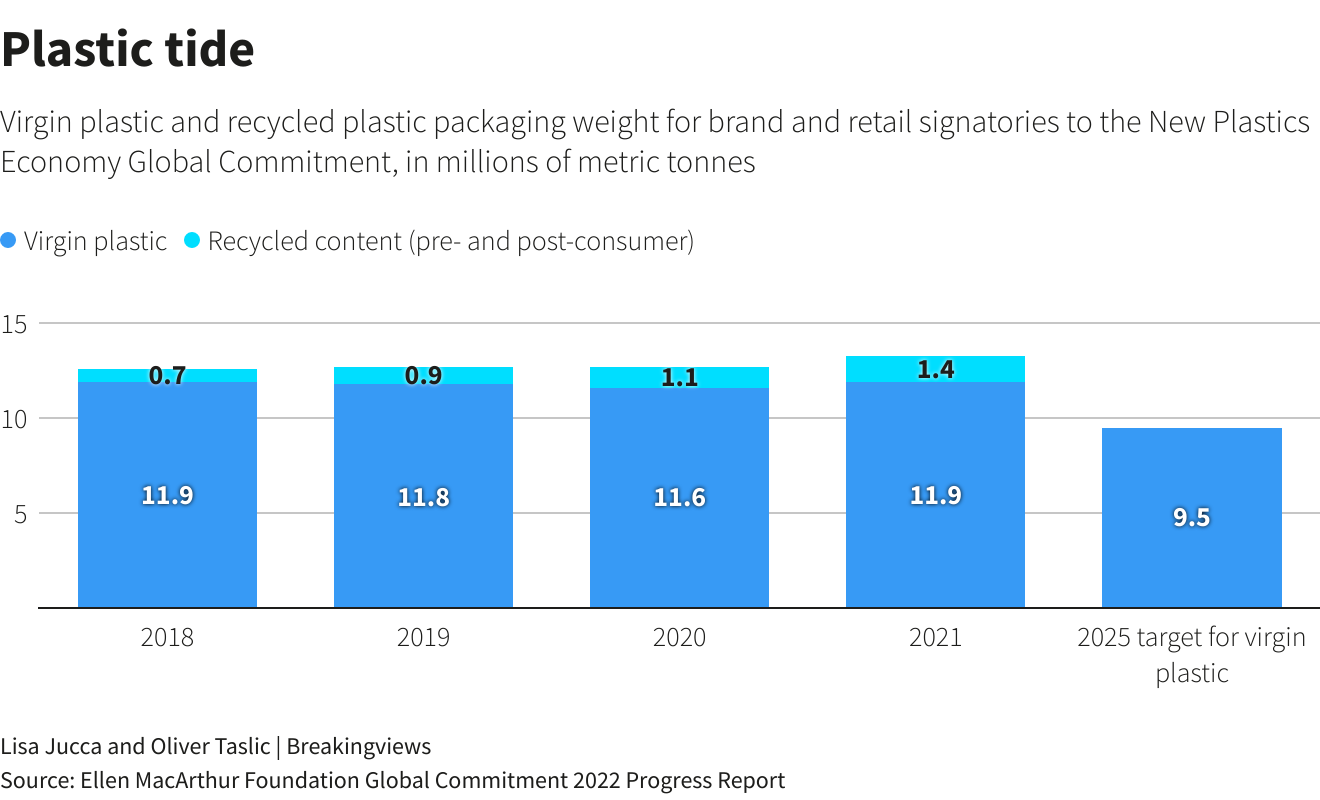

Investors sit on a plastic waste ticking bomb

MILAN, Jan 13 (Reuters Breakingviews) – Investors should worry about a rising plastic tide. The pandemic and a war in Ukraine have focused money managers’ attention on supply chain disruption and energy security risks. Yet as the world continues to drown in packaging waste, the public and private sectors may come after big users like PepsiCo (PEP.O), Coca-Cola (KO.N) and Mars.Four years after the consumer goods giants signed up to voluntary reduction targets under the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment, progress is disappointing. Ellen MacArthur Foundation data shows that the packaging employed by companies like PepsiCo, Mars and Coca-Cola increased its usage of virgin plastic, made from fossil fuels rather than recycled materials, by 5%, 3% and 11% respectively between 2019 and 2021. That makes it unlikely they can meet their commitments to curb its use by 5%, 20% and 25% by 2025.Big plastic users are also making insufficient progress in using recycled material. The latter amounts to just 10% of plastic packaging used by pact signatories. Reusable containers, the most environmentally friendly form of packaging, amounted to only 1.2% of the total in 2021, and that figure is decreasing.Despite citizens’ effort to sort out used plastic for collection, especially in Europe, only 9% actually gets recycled each year, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development says. In the United States 73% of plastic waste ends up in landfills, where it takes up to 500 years to decompose. The rest gets incinerated or washes up on developing countries’ shores. That will only worsen as annual demand of about 450 million tonnes a year is expected to treble by 2060.Solving the plastic challenge is complex and expensive. Plastic comes in different types that cannot be bundled together. Certain materials or additives make it difficult to recycle. Substituting plastic with biodegradable material can be expensive. Using recycled plastic, while less energy-intensive than creating virgin plastic, can cost more overall.Yet, having pledged to act, big corporates are in a vulnerable position. Danone (DANO.PA) is facing a legal challenge over its plastic use. In March, 175 governments agreed to work out binding laws to end plastic pollution by end-2024. Around 70% of citizens surveyed last year in 34 countries want new anti-plastic rules.European investors’ greater focus on sustainability means they are more likely to hassle domestic laggards. But if governments decide to implement mandatory recycling quotas, rival U.S. late-starters would suffer the most. In a worst-case scenario, companies could face a collective $100 billion annual bill if lawmakers ask them to cover waste management costs in full, the PEW Charitable Trusts says.For investors, plastic inaction could become toxic.Reuters GraphicsFollow @LJucca on Twitter(The author is a Reuters Breakingviews columnist. The opinions expressed are her own. Updates to add graphic.)CONTEXT NEWSRepresentatives of 175 countries endorsed in March a landmark resolution to develop international legally binding instruments to end plastic pollution. Negotiations on the new legal instruments kicked off on Nov. 28 with the aim of finalising a binding agreement by 2024.Germany will ask makers of products containing single-use plastic to contribute to the cost of collecting litter in streets and parks from 2025 by paying into a central fund managed by the government. In 2008 the Netherlands introduced a packaging waste management levy.Corporate signatories of the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment launched by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the U.N. Environment Programme in 2018, which include PepsiCo, the Coca-Cola Company, Nestlé, Danone and Unilever, are likely to miss several if not all of their targets for tackling plastic pollution. That’s according to progress report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation published in November.Collective use of virgin plastic by the signatories of the anti-plastic pact has risen 2.5% year-on-year to 11.9 million metric tonnes in 2021, bringing it to the same level it stood at in 2018. Meanwhile, the share of reusable plastic in packaging has fallen to an average 1.2% of total, the report showed.Editing by George Hay, Streisand Neto and Oliver TaslicOur Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.Opinions expressed are those of the author. They do not reflect the views of Reuters News, which, under the Trust Principles, is committed to integrity, independence, and freedom from bias.

‘Forever chemicals’ expose need for systemic changes

Going back in time can reveal how far we still have to progress. In researching per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) for a recent article series, I found myself ricocheting between the present and the 1950s and 1960s. That was when the vast class of fluorinated compounds commonly dubbed “forever chemicals” first came into widespread use, morphing from wartime applications to a cluster bomb of consumer and industrial uses.

The pesticide industry was also “a child of the Second World War,” biologist Rachel Carson wrote in her magnum opus “Silent Spring,” published 60 years ago last fall. Synthetic insecticides had “no counterparts in nature,” she observed, yet “we have allowed these chemicals to be used with little or no advance investigation of their effect” on ecosystems or ourselves. Like pesticides, PFAS shot from laboratory to market without thorough safety testing, endangering public health and wildlife.

Despite subsequent advances in environmental legislation over the intervening decades, the U.S. approach to chemical regulation remains largely unchanged. We are still subjected to what Carson aptly termed an “appalling deluge of chemical pollution.”

Catering to corporations

Writing in The New Yorker shortly after Carson’s death in 1964, E.B. White noted a “basic flaw in our regulatory machinery. American justice holds the accused person innocent until proved guilty; somehow this concept has crept over into industry, where it doesn’t belong, and has been applied to products of all kinds. Why should a poison dust or spray… enjoy immunity while there is any reason to suspect that it may endanger the public health or damage the natural scene?”

Congress had a chance to correct this fundamental injustice when it enacted the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) of 1976, but it let corporate priorities prevail. The law instructed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to adopt those regulations “least burdensome” to industry, and it permitted continued use of roughly 60,000 chemicals (including the earliest ‘legacy’ PFAS) without review of their health risks.

An effort to strengthen TSCA in 2016 encountered strong industry pushback and accomplished only minimal reform, according to a recent ProPublica report. The workload of the agency’s chemical division grew markedly as it strove to undertake more chemical reviews, but its funding remained stagnant.

Greatly increasing the funding and staffing of EPA’s chemicals division would certainly improve chemical oversight, observed Kyla Bennett, an ecologist and lawyer who directs science policy for Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), a nonprofit that supports whistleblowers and is pushing the EPA to protect consumers from PFAS in fluorinated plastic containers. “EPA doesn’t have the money, the bodies and the right expertise,” she said, nor does it have adequate time for evaluating new chemicals given a tight, statutory cutoff. The metric for success is “how many of these [approvals] they’ve gotten out in 90 days, not how well they’re protecting human health.”

“The whole system is broken,” Bennett added, due to corporate capture of the regulatory process — a dynamic she said persists under both Democratic and Republican administrations. Supervisors cycle from the agency to industry and back, and whistleblowers report that EPA managers change scientific conclusions, delete critical information and expedite approval of new chemicals to appease manufacturers.

Corporations are mandated to submit studies documenting safety risks, but in 2019 the agency stopped sharing those publicly and made the data difficult for their own staff to access, whistleblowers report. According to Bennett, even some safety data sheets — designed to inform workers and consumers of hazards—are now heavily redacted. Or, in place of where the form should appear in the database, there’s a blank page with a single word: “sanitized.”

A decade before the EPA was established, Carson had already observed the deference given to chemical manufacturers in what she called “an era dominated by industry, in which the right to make a dollar at whatever cost is seldom challenged.” Now, it appears that ‘right’ is almost never challenged: Among 3,835 new chemical applications submitted in the five years leading up to July 2021, journalist Sharon Lerner reported, EPA’s division of new chemicals did not decline a single one.

‘Regrettable substitutions’

Presented with clear evidence in 2001 that PFAS were endangering human health, the EPA negotiated a voluntary phaseout with some leading manufacturers for two PFAS compounds (among an estimated 4,700 in commercial use). In place of those ‘legacy’ compounds, the EPA permitted manufacturers to produce a second generation (“GenX”) of PFAS even though industry studies had demonstrated their health risks, Lerner revealed.

GenX is a classic case of a “regrettable substitution,” what Harvard University public health professor Joseph Allen defines as “the cynical replacement of one harmful chemical by another equally or more harmful in a never-ending game being played with our health.”

Industry always has the upper hand in this whack-a-mole “game” due to the sheer volume of new chemicals generated. The U.N. Environmental Programme reports that in 1965, a new chemical substance was registered on average every 2.5 minutes. Now, it’s every 1.4 seconds. The EPA is mandated to test 20 new chemicals a year but it’s failing to meet even that modest target.

The Precautionary Principle

Europe, in contrast, is moving away from the whack-a-mole approach to chemical management. According to the European Environmental Bureau, the European Commission plans to implement “a group approach to regulating chemicals, where the most harmful member of a chemical family defines legal restrictions for the whole family. That should end an industry practice of tweaking chemical formulations slightly to evade bans.”

For more than a decade, Europe has applied a common-sense restraint known as the Precautionary Principle in chemical regulations — requiring industries to assess risks and share data on hazards before substances go to market. Whereas in the U.S., chemicals are readily approved and only withdrawn when there is irrefutable evidence of human harm, often after decades of use.

While questions remain about the timeline and resources for implementing Europe’s new chemicals “Restrictions Roadmap,” the European Union has already banned about 2,000 chemicals since adopting a more precautionary approach. An additional 5,000 to 7,000 chemicals could be banned by 2030 under the new roadmap.

Paring back to essential uses and increasing transparency

Maine is pioneering a path that a growing number of scientists and policy specialists advocate — banning all PFAS except those deemed — in the language of LD 1503 — “essential for health, safety or the functioning of society and for which alternatives are not reasonably available” (such as critical medical devices).

A recent study found that alternatives exist for many consumer uses, but that options for industry substitutes are harder to assess—given a culture that keeps much production information proprietary. Far too often, companies use their right to confidential business information “as a cloak to keep things from the public and that’s wrong,” Bennett said.

3M, a leading manufacturer of PFAS, knew about the health risks of its formulations for half a century, evidence in lawsuits has revealed. Recently, the corporation announced plans to phase out PFAS manufacturing and use by 2025, but lack of transparency around how it defines and formulates these chemicals makes the outcome ambiguous. Its action comes in the face of mounting pressure from investors and tens of billions in anticipated litigation settlements as communities around the globe seek damages from chemical manufacturers for poisoned waters and health impacts that begin even before birth, resulting in “pre-polluted babies.”

Chemical corporations may not adopt greater transparency until forced to. But governments working to regulate and remediate PFAS can show the way. For the most part, Maine is making a good-faith effort to share information openly: posting data on sludge and septage sites to be tested, results from landfill leachate tests and public drinking water supply tests, updates on the status of the state’s well-testing, and recorded meetings of the PFAS Fund Advisory Committee.

The state could further improve information-sharing by hiring an ombudsperson to field residents’ questions and concerns, creating a more intuitive and readily linked web interface, and openly strategizing how to address the vast gap that remains between needs for PFAS water testing and treatment and agency capacities. Residents I interviewed in hard-hit areas voiced frustration over not having anyone to advocate for them within state government, feeling they were “put on the back burner” and might be left on their own without further help.

With Maine now mandating PFAS reporting from manufacturers, state agencies will need to resist the regulatory “corporate capture” evident at the federal level.

Open sharing on the part of government is essential on practical grounds — to expedite getting clean water to those still drinking PFAS, to facilitate a rapid transition to new product formulations, and to keep people informed about rapidly evolving science and policy.

More fundamentally, transparency can help to right a pernicious wrong. PFAS pollution represents a devastating betrayal of people who placed their faith in government to protect them and in corporations to consider the greater good. Choices made over decades in corporate board rooms, EPA offices and the halls of Congress violated that public trust.

“Who has decided — who has the right to decide — for the countless legions of people who were not consulted…,” Rachel Carson wrote about the indiscriminate use of toxic chemicals. In the case of PFAS, a small cadre chose the allure of big profits over the well-being of the world. If we hope to reverse those priorities in the years ahead, those who were “not consulted” will need to speak out.

Trying to live a day without plastic

On the morning of the day I had decided to go without using plastic products — or even touching plastic — I opened my eyes and put my bare feet on the carpet. Which is made of nylon, a type of plastic. I was roughly 10 seconds into my experiment, and I had already committed a violation.Since its invention more than a century ago, plastic has crept into every aspect of our lives. It’s hard to go even a few minutes without touching this durable, lightweight, wildly versatile substance. Plastic has made possible thousands of modern conveniences, but it has come with downsides, especially for the environment. Last week, in a 24-hour experiment, I tried to live without it altogether in an effort to see what plastic stuff we can’t do without and what we may be able to give up.Most mornings I check my iPhone soon after waking up. On the appointed day, this was not possible, given that, in addition to aluminum, iron, lithium, gold and copper, each iPhone contains plastic. In preparation for the experiment, I had stashed my device in a closet. I quickly found that not having access to it left me feeling disoriented and bold, as if I were some sort of intrepid time traveler.I made my way toward the bathroom, only to stop myself before I went in.“Could you open the door for me?” I asked my wife, Julie. “The doorknob has a plastic coating.”She opened it for me, letting out a “this is going to be a long day” sigh.My morning hygiene routine needed a total revamp, which required detailed preparations in the days before my experiment. I could not use my regular toothpaste, toothbrush, shampoo or liquid soap, all of which were encased in plastic or made of plastic.Fortunately, there is a huge industry of plastic-free products targeted at eco-conscious consumers, and I had bought an array of them, a haul that included a bamboo toothbrush with bristles made of wild boar hair from Life Without Plastic. “The bristles are completely sterilized,” Jay Sinha, the company’s co-owner, assured me when I spoke with him the week before.Instead of toothpaste, I had a jar of gray charcoal-mint toothpaste pellets. I popped one in, chewed it, sipped water and brushed. It was nice and minty, though the ash-colored spit was unsettling.I liked my shampoo bar. A shampoo bar is just what it sounds like: a bar of shampoo. Mine was scented pink grapefruit and vanilla, and lathered up well. According to shampoo bar advocates, it is also cheaper than bottled shampoo on a per-wash basis (one bar can last 80 showers). Which is good, because the plastic-free life can be expensive. Package Free, a sleek outlet in the NoHo neighborhood of Manhattan that abuts Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop store, sells a zinc and stainless-steel razor for $84 (as well as “the world’s first biodegradable vibrator”).An array of plastic-free items in the reporter’s bathroom.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesA plastic-free morning shave, thanks to a razor made of zinc and steel.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesA wool sweater knitted by hand completed the day’s outfit.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesTaking a blogger’s advice, I mixed a D.I.Y. deodorant out of tea tree oil and baking soda. It left me smelling a little like a medieval cathedral, but in a good way. Making your own stuff is another way to avoid plastic, though it does require another luxury: free time.Before I was done in the bathroom, I had broken the rules a second time, by using the toilet.Getting dressed was also a challenge, given that so many clothing items include plastic. I had ordered a pair of wool pants that promised to be plastic free, but they had not arrived. In their stead, I chose a pair of old Banana Republic chinos.The tag said “100 percent cotton,” but when I had checked the day before with a very helpful Banana Republic public relations representative, it turned out to be a little more complicated. The main fabric is indeed 100 percent cotton, but there was plastic lurking in the zipper tape, the internal waistband, woven label, pocketing and threads, the representative told me. I cut my thumb trying to slice off the black brand label with an all-metal knife. Instead of a Band-Aid — yes, plastic — I used some gummed paper tape to stop the bleeding.Happily, my underwear did not represent a plastic violation — blue boxers from Cottonique made of 100 percent organic cotton with a cotton drawstring in place of the elastic (which is often plastic) waistband. I had found this item via an internet list of “14 Hot & Sustainable Underwear Brands for Men.”For my upper body, I lucked out. Our friend Kristen had knitted my wife a sweater for a birthday present. It had rectangles of blue and purple, and it was 100 percent merino wool.“Could I borrow Kristen’s sweater for the day?” I asked Julie.“You’re going to stretch it out,” Julie said.“It’s for planet Earth,” I reminded her.Plastics Present and PastThe world produces about 400 million metric tons of plastic waste each year, according to a United Nations report. About half is tossed out after a single use. The report noted that “we have become addicted to single-use plastic products — with severe environmental, social, economic and health consequences.”I’m one of the addicts. I did an audit, and I’d estimate that I toss about 800 plastic items in the garbage a year — takeout containers, pens, cups, Amazon packages with foam inside and more.Before my Day of No Plastic, I immersed myself in a number of no-plastic and zero-waste books, videos and podcasts. One of the books, “Life Without Plastic: The Practical Step-by-Step Guide to Avoiding Plastic to Keep Your Family and the Planet Healthy,” by Mr. Sinha and Chantal Plamondon, came from Amazon wrapped in clear plastic, like a slice of American cheese. When I mentioned this to Mr. Sinha, he promised to look into it.I also called Gabby Salazar, a social scientist who studies what motivates people to support environmental causes, and asked for her advice as I headed into my plastic-free day.“It might be better to start small,” Dr. Salazar said. “Start by creating a single habit — like always carrying a stainless-steel water bottle. After you’ve got that down, you start another habit, like taking produce bags to the grocery. You build up gradually. That’s how you make real change. Otherwise, you’ll just be overwhelmed.”“Maybe being overwhelmed will bring some sort of clarity?” I said.“That’d be nice,” Dr. Salazar said.Must avoid: All of these items, which are part of the reporter’s everyday life, contain plastic.Photographs by Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesAdmittedly, living completely without plastic is probably an absurd idea. Despite its faults, plastic is a crucial ingredient in medical equipment, smoke alarms and helmets. There’s truth to the plastics industry’s catchphrase from the 1990s: “Plastics make it possible.”In many cases it can help the environment: Plastic airplane parts are lighter than metal ones, which mean less fuel and lower CO2 emissions. Solar panels and wind turbines have plastic parts. That said, the world is overloaded with the stuff, especially the disposable forms. The Earth Policy Institute estimates that people go through one trillion single-use plastic bags each year.The crisis was a long time coming. There’s some debate over when plastic entered the world, but many date it to 1855, when a British metallurgist, Alexander Parkes, patented a thermoplastic material as a waterproof coating for fabrics. He called the substance “Parkesine.” Over the decades, labs across the world birthed other types, all with a similar chemistry: They are polymer chains, and most are made from petroleum or natural gas. Thanks to chemical additives, plastics vary wildly. They can be opaque or transparent, foamy or hard, stretchy or brittle. They are known by many names, including polyester and Styrofoam, and by shorthand like PVC and PET.Plastic manufacturing ramped up for World War II and was crucial to the war effort, providing nylon parachutes and Plexiglas aircraft windows. That was followed by a postwar boom, said Susan Freinkel, the author of “Plastic: A Toxic Love Story,” a book on the history and science of plastic. “Plastic went into things like Formica counters, refrigerator liners, car parts, clothing, shoes, just all sorts of stuff that was designed to be used for a while,” she said.Then things took a turn.“Where we really started to get into trouble is when it started going into single-use stuff,” Ms. Freinkel said. “I call it prefab litter.”The outpouring of straws, cups, bags and other ephemera has led to disastrous consequences for the environment. According to a study by the Pew Charitable Trusts, more than 11 million metric tons of plastic enter oceans each year, leaching into the water, disrupting the food chain and choking marine life.Close to one-fifth of plastic waste gets burned, releasing CO2 into the air, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which also reports that only 9 percent of plastics are recycled. Some aren’t economical to recycle, and other types degrade in quality when they are.Plastic may also harm our health. Certain plastic additives — such as BPA and phthalates — may disrupt the endocrine system in humans, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Worrying effects may include behavioral problems and lower testosterone levels in boys and lower thyroid hormone levels and preterm births for women.“Solving this plastic problem can’t fall entirely on the shoulders of consumers,” Dr. Salazar told me. “We need to work on it on all fronts.”It’s EverywhereEarly in my no-plastic day, I started to see the world differently. Everything looked menacing, like it might be harboring hidden polymers. The kitchen was particularly fraught. Anything I could use for cooking was off-limits — the toaster, the oven, the microwave. Even leftovers were a no-go. My son waved a plastic baggie filled with French toast. “You want some of this?” Yes, I did.Instead, I decided to go foraging for raw food items.I left my building using the stairs, rather than the elevator with its plastic buttons, and walked to a health food store near our apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.When I go shopping, I try to remember to take a cloth bag with me. This time, I had brought along seven bags of varying sizes, all of them cotton. I also had two glass containers.At the store, I filled up one of my cotton bags with apples and oranges. On close inspection, I noticed that the each rind had a sticker with a code. Another likely violation, but I ignored it.At the bulk bins, I scooped walnuts and oatmeal into my glass dishes using a (washed) steel ladle I had brought from home. The bins themselves were plastic, which I ignored, because I was hungry.Scooping walnuts into a glass container with a steel ladle brought from home.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesIt is not easy to pay without using plastic. Even paper currency may have synthetic ingredients.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesGlass container? Bamboo fork? Cotton towel? Wooden chair? Check, check, check, check.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesI went to the cashier. At which point it was time to pay. Which was a problem. Credit cards were out. So was my iPhone’s Apple Pay. Paper money was another violation: Although U.S. paper currency is made mainly of cotton and linen, each bill likely contains synthetic fibers, and the higher denominations have a security thread made of plastic to prevent counterfeiting.To be safe, I had brought along a cotton sack full of coins. Yes, a big old sack heavy with quarters, dimes and pennies — about $60 worth that I had withdrawn from Citibank and my kids’ piggy banks.At the checkout counter, I started stacking quarters as quickly as I could between nervous glances at the customers behind me.“I’m really sorry this is taking so long,” I said.“That’s OK,” the cashier said. “I meditate every morning so I can deal with turmoil like this.”He added that he appreciated my commitment to the environment. It was the first positive feedback I’d received. I counted out $19.02 — exact change! — and went home to eat my breakfast: nuts and oranges on a metal cookie tray, which I balanced on my lap.A couple of hours later, in search of a plastic-free lunch, I walked to Lenwich, a sandwich and salad shop in my neighborhood. I arrived early in the afternoon, toting my rectangular glass dish and bamboo cutlery.“Can you make the salad in this glass container?” I asked, holding it up.“One minute please,” the man behind the counter said, tersely.He called over a manager, who said OK. Victory! But the manager then rejected my follow-up request to use my steel scooper.After lunch, I headed to Central Park, figuring that this was a spot in Manhattan where I could relax in a plastic-free environment. I took the subway there, which scored me more violations, since the trains themselves have plastic parts and you need a MetroCard or smartphone to get through the turnstiles.At least I didn’t sit in one of those plastic orange seats. I had brought my own: an unpainted, fold-up Nordic-style teak chair, hard and austere. It’s what I had been using at the apartment to avoid the plastic-tainted chairs and couches.Fellow riders took little notice of the man in the wooden chair.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesI plopped my chair down near a pole in the middle of the car. One guy had a please-don’t-talk-to-me look in his eyes, but the other passengers were so buried in their phones that the sight of a man on a wooden chair didn’t faze them.Walking through Central Park, I spotted dental floss picks, a black plastic knife and a plastic bag.Back home, I recorded some of my impressions. I wrote on paper with an unpainted cedar pencil from a “Zero Waste Pencil tin set” (regular pencils contain plastic-filled yellow paint). After a while, I went to get a drink of water. Which brings up perhaps the most pervasive foe of all, one I haven’t even mentioned yet: microplastics. These tiny particles are everywhere — in the water we drink, the air we breathe, in the oceans. They come from, among other things, degraded plastic litter.Are they harmful to us? I talked with several scientists, and the general answer I got was: We don’t know yet. “I think we’ll have an improved understanding in the next few years,” said Todd Gouin, an environmental research consultant. But those who are extra-cautious can use products that promise to filter microplastics from water and air.I had bought a pitcher by LifeStraw that contains a membrane microfilter. Of course, the pitcher itself had plastic parts, so I couldn’t use it on the Big Day. Instead, the night before, I spent some time at the sink filtering water and filling up Mason jars. Our kitchen looked like it was ready for the apocalypse.The water tasted particularly pure, which I’m guessing was some sort of a placebo effect.I wrote for a while. Then I sat there in my wooden chair. Phone-less. Internet-less. Julie took some pity on me and offered to play a game of cards. I shook my head.“Plastic coating,” I said.At about 9 p.m., I took our dog for her nightly walk. I was using a 100 percent cotton leash I bought online. I had ditched the poop bags — even the sustainable ones I found were made with recycled or plant-based plastic. Instead, I carried a metal spatula. Thankfully, I didn’t have to use it.Using the stairs after shopping, to avoid the elevator, which has plastic parts.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesThe first draft of this article was written with a plastic-free pencil by candlelight.Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesCouldn’t use the bed (plastic).Jonah Rosenberg for The New York TimesAt 10:30 p.m., exhausted, I lay down on my makeshift bed — cotton sheets on the wood floor, since my mattress and pillows are plasticky.I woke up the next morning glad to have survived my ordeal and be reunited with my phone — but also with a feeling of defeat.I had made 164 violations, by my count. As Dr. Salazar had predicted, I felt overwhelmed. And also uncertain. There was so much that remained unclear, even after I had been studying this topic for weeks. What plastic-free items really made a difference, and what is mere green-washing? Is it a good idea to use boar’s-hair toothbrushes, tea tree deodorant, microplastic-filtering devices and paper straws, or does the trouble of using those things make everyone so bonkers that they actually end up damaging the cause?I called Dr. Salazar for a pep talk.“You can drive yourself crazy,” she said. “But it’s not about perfection, it’s about progress. Believe it or not, individual behavior does matter. It adds up.“Remember,” she continued, “it’s not about plastic being the enemy. It’s about single-use as the enemy. It’s the culture of using something once and throwing it away.”I thought back to something that the author Susan Freinkel had told me: “I’m not an absolutist at all. If you came into my kitchen, you would be like, what the hell? You wrote this book and look at how you live!”Ms. Freinkel does make an effort, she said. She avoids single-use bags, cups and packaging, among other things. I pledge to try, too, even after my not wholly successful attempt at a one-day ban.I’ll start with small things, building up habits. I liked the shampoo bar. And I can take produce bags to the grocery. I might event pack my steel water bottle and bamboo cutlery for my trips to Lenwich. And from there, who knows?And I’ll proudly wear the “Keep the Sea Plastic Free” T-shirt that I bought online in the days leading up to the experiment. It’s just 10 percent polyester.

Venice’s lagoon of 2,000 lost boats: the true cost of dumping small vessels

Venice’s lagoon of 2,000 lost boats: the true cost of dumping small vessels For decades, the city’s wetland has been used as a landfill for discarded wrecks, leaking microplastics and pollutants and posing a risk to others on the waterPaolo Cuman points to a rusty boat, half-sunk in Venice’s lagoon. “It has been there for years,” he says, laughing. “When I manage to have her removed, I’ll open a bottle of good wine.” Hunting abandoned boats is a hobby for Cuman, the coordinator of the Consulta della Laguna Media, a grassroots group monitoring the health of the lagoon. Once he’s found the boats, he maps them and pressures the authorities to remove them.For decades, the Venetian lagoon – the largest wetland in the Mediterranean – has been used as a landfill by people wanting to get rid of their boats. An estimated 2,000 abandoned vessels are in the lagoon, scattered over an area of about 55,000 hectares (135,900 acres). Some lie beneath the surface, others poke above the water and some are stranded on the barene – the lowlands that often disappear at high tide.The wrecks are a threat to other vessels – a boat’s engine may be damaged if it passes over them. But they are an even bigger threat to the ecosystem, leaking chemicals, fuel and microplastics as the boats disintegrate in the water.Authorities seldom remove these wrecks; bureaucracy is slow and dealing with the city’s boat graveyards is a long way down the priority list. That’s why a group of boating enthusiasts and environmentalists, including Cuman, are trying to force action.On a hot summer day, the lagoon, which is only a few miles away from the crowded streets of Venice, feels like a world away. Sailboats zigzag across the water, cormorants fly past and flamingos wade in the shallows, while fish leap in and out of the water.Only the wrecks of abandoned vessels mar the scene. For the most part they are small, low-powered motorboats, or burci – transport boats widely used in Venice. These are “owned by ordinary people”, says Cuman.He spots the relic of a vessel: “See this fishing boat? I remember when it used to bring the fish to Mestre [his neighbourhood] 40 years ago! Looks like it has been discarded for three decades at least,” he says.The practice of illegally abandoning vessels in the lagoon dates back to the 1950s, when trucks began to replace boats for commercial purposes. “In the past, the large shipping companies abandoned the burci here, creating boat cemeteries,” says Giovanni Cecconi, president of Venice Resilience Lab, an environmental group that has contributed to mapping the lagoon.“There are boats that have been abandoned for 20 or 30 years that are in very bad condition,” says Davide Poletto, executive director of the Venice Lagoon Plastic Free organisation. These release chemical contaminants as they break down, he says.Modern boats tend to have fibreglass hulls, which release microplastics as they decompose. A big concern is anti-fouling paints, which are intended to keep slime, barnacles and other creatures off the boats. Some of these, such as tributyltin, are now banned because of their toxic effects on marine life. Even the boats’ furnishings and upholstery contain chemicals that may contaminate the water.To a Venetian, owning a boat is almost like owning a car. But while a car might end up in a salvage yard, disposing of an unserviceable boat is complicated and expensive. Venice lacks the infrastructure to deal with unwanted boats; few facilities take them so many choose to abandon them.The Venice lagoon is controlled by 26 different entities, which means it is not always clear who has responsibility.‘A search for ourselves’: shipwreck becomes focus of slavery debateRead more“Even if a local policeman sees an abandoned boat on a sandbank, he cannot intervene to remove it, because it is not his jurisdiction,” says Paolo Ticozzi, a city councillor who says he has asked authorities to create a disposal site for abandoned boats, but has yet to receive an answer.Consulta della Laguna Media says it is the only organisation mapping the wrecks, and that it only covers the northern part of the lagoon.No attempt has been made to quantify the environmental impact of the vessels, according to Venice Lagoon Plastic Free.“No one has thought of analysing the damage caused by boats that have been there for 20, 30 or even 40 years,” says Poletto. The association has funding to remove some of the wrecks and plans to collect and examine some of the sludge at those sites.Venice is far from the only boat graveyard. About 3m shipwrecks of all kinds are scattered across the world, according to Unesco. In the UK, hundreds of boats lie abandoned along the coasts of Devon and Cornwall, according to a BBC report, which called the practice “the fly-tipping of the maritime world”.In the US, a Washington state programme has removed about 900 abandoned boats from rivers since 2002. In 2021, Virginia created a working group to “coordinate an examination of the issues” around abandoned and derelict vessels.“The situation must be evaluated case-by-case,” says the bioscientist Prof Monia Renzi. “Obviously, a boat that has just been sunk should be recovered, if technically possible, because it could release a large number of contaminants even from parts we don’t normally think of, like upholstery.”It can be different for vessels that have been lying on the sea – or riverbed for many decades, where an ecosystem has formed around the ships: “Marine sedimentation above the wreck limits the spread of contaminants,” says Renzi, adding that removing some of the oldest wrecks could cause further damage.When it comes to Venice’s lagoon, however, the best solution is usually to remove the wrecks regardless of their age, says Renzi, especially because shallow waters make recovery easier.Bulky material like boats can reduce the water’s natural circulation, she says, damaging the wider ecosystem – the less water circulates, the more pollutants will stick around. These environments are “already under pressure, because they are highly exploited for fishing, so the possible transfer of contaminants can be extremely critical”, she says. It risks further damaging fish populations.In Venice, however, activists have won a small victory. The authority responsible for water management in the Venetian lagoon, the Magistrato alle Acque, has agreed to remove some vessels in the coming months.Cuman welcomes the news, but says a lot remains to be done.It is not only a problem for the environment, he says, but also of transport within the lagoon: “Unbound boats are at the mercy of the wind and the current. If you pass over a sunken or semi-sunken boat, it can break the engine, causing considerable damage,” says Cuman. Broken-off boat parts floating on the currents can also cause accidents hundreds of miles from the wreck, he says.Cuman wants more people to join his wreck-spotting missions. “If I convince others in this community to join me, then there will be a Venetian patrolling every spot of the lagoon. Ignoring us will become impossible.”TopicsEnvironmentShipwreckedVenicePollutionfeaturesReuse this content

Citizen scientists are seeing an influx of microplastics in the Ohio River

PITTSBURGH — A group of citizen scientists have observed a substantial influx of nurdles — small plastic pellets about the size of a lentil — in the Ohio River, which provides drinking water to more than five million people.

“In the last few months, we’ve seen a huge surge in nurdles,” James Cato, a community organizer at the Mountain Watershed Association, told Environmental Health News (EHN) in November. “Where we’ve normally been detecting about 10 nurdles per sample, we’re now seeing 100.”

Cato and other citizen scientists have regularly conducted “nurdle patrol” since 2020, taking to the river in boats to collect nurdles from water and sediment samples. Their goal is to establish a rough baseline for how many and what types of nurdles are in the water before Shell opened its massive new plastics plant along the Ohio River in southwestern Pennsylvania.

But these particular nurdles represent just a tiny fraction of the microplastics plaguing the Ohio River and other freshwater bodies across Pennsylvania and the country. Nurdles, broken down pieces of plastic packaging, bottles, or bags, and plastic fibers used in synthetic textiles (like nylon) that are less than five millimeters long are considered microplastics.

What’s happening with the influx of nurdles in the Ohio River exemplifies how hard it is to track down the sources of such pollution and determine who is responsible for cleaning it up. And amid the confusion, scientists are just beginning to understand the consequences to wildlife and human health.

“When I started looking into this a couple years ago, freshwater environments weren’t really on the radar because most research on microplastics had been focused on marine environments,” Lisa Emili, a researcher and associate professor at Penn State University Altoona, told EHN. “That’s starting to change as we increasingly recognize that freshwater environments have the ability not only to transport microplastics, but also to accumulate them.”

Tracking down the source of plastic nurdles

A leaf along the Ohio River. Citizens scientists have seen an influx of the pollution. Credit: James CatoNurdles found in the Ohio River by the Mountain Watershed Association.Credit: James Cato

Shell’s plant, which came online in November, will produce up to 1.6 million metric tons of plastic nurdles every year to be used in many consumer products, including single-use plastic packaging and bags. But the influx of new nurdles showed up before the plant opened, and the nurdle patrollers think they’ve traced many of them to a different source.

“These nurdles are really tiny, about the size of a poppy seed and about an eighth the size of regular nurdles,” Cato said. That unique appearance allowed them to track a trail of them to an outfall on Racoon Creek, a tributary of the Ohio.

The outfall belongs to a company called Styropek, which manufactures expandable polystyrene pellets, or EPS — rigid plastic pellets that are later expanded with air to double their size, then used to manufacture insulation and packaging products similar to Styrofoam. According to its website, Styropek is the largest manufacturer of these pellets in North America.

“We found thousands of these nurdles downriver of Styropek’s outfall and just two upriver,” Cato said. “There were also lots of nurdles on the riverbanks — so much that it looked like snowfall, coating plants in white — and they basically formed a bull’s eye around the plant, so we’re pretty confident they’re coming from there.”

The groups first noticed the nurdles in September. As private citizens, they couldn’t investigate further without trespassing on Styropek’s property, so they alerted regulators at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). About a month later, the EPA referred them to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP), at which point the groups filed a complaint with that state agency and the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission to ask them to investigate.

Their contact at the Fish and Boat Commission wanted to help, but didn’t think they had legal jurisdiction to do so. Jamar Thrasher, a spokesperson for the Department of Environmental Protection, said the agency had performed an inspection at Styropek about a week prior to receiving the complaint, and “found nothing floating near the facility’s outfall or in the stream and identified no violations.” Still, in response to the complaint, he said the agency “requested that Styropek develop and integrate a more expansive plastic pellet/nurdle housekeeping plan to prevent potential discharge through any outfalls.”

Styropek did not respond to numerous requests for comment. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection did not perform a follow-up investigation, perform any clean-up of the nurdles, require the company to perform any cleanup or issue any fines against Styropek.

Nurdle pollution is largely unregulated. There are no international regulations on it, but in 2022 the United Nations resolved to create an international treaty aimed at restricting microplastic pollution in marine environments. A draft of the rule is expected to be complete in 2024.

In the U.S., no agency is charged with preventing or cleaning up nurdle pollution — nurdles aren’t federally classified as pollutants or hazardous materials, so unlike oil spills or other toxic substances in waterways, the Coast Guard doesn’t clean up nurdle spills.

Most state governments don’t have rules in place related to nurdle monitoring or cleanup, and in other parts of the country, it has sometimes been unclear who bears responsibility for regulating its pollution, resulting in an alarming lack of cleanup when spills do occur.

Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection spokesperson Lauren Camarda said nurdles are prohibited from entering waterways under Pennsylvania’s Clean Streams Law and the Solid Waste Management Act, both of which should enable the agency to hold polluters accountable for cleaning up nurdle spills.

Microplastics pervasive in fresh water

Plastic pollution in oceans has gotten lots of attention, but researchers are now discovering that microplastic pollution in fresh water is also pervasive.A study published by the nonprofit environmental advocacy group PennEnvironment in October found microplastics in all 50 of the “pristine” Pennsylvania waterways the group sampled — all of which are classified by Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection as “exceptional value,” “high quality” or Class A trout streams. Research on microplastics in fresh water across the U.S. is still limited, but scientists have found microplastics nearly everywhere they’ve looked, including many waterways that feed the Great Lakes and the lakes themselves, rivers throughout Illinois, and California’s Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers.Microplastics can kill fish and other wildlife that ingest them by making their stomachs feel full when they’re not, but emerging research suggests they can also enter fish through their gills or skin, poison their flesh and travel up the food chain, which has implications for other types of wildlife and human health.“Microplastics piggyback other pollutants like bacteria, heavy metals, endocrine-disrupting chemicals and PFAS [per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, a.k.a. ‘forever chemicals’],” Emili said. “We know they’re not good for us, but unlike other pollutants, we don’t even know how to set maximum daily loads for microplastics to avoid health consequences because they come in all different sizes, chemical compositions and levels of toxicity.”Nurdles account for a large proportion of microplastics in waterways — by weight they’re the second-largest source of micropollutants in the ocean (after tire dust).

Microplastics in human blood

“The study that really scared everyone found microplastics in human blood.”Credit: Oregon State UniversityMicroplastics have been found virtually everywhere on the planet — from the top of Mount Everest, the highest elevation on Earth; to the Marianas Trench at the very bottom of the Pacific Ocean; in fresh rain and snow, in the cells of fruits and vegetables, in the bodies of animals and humans and even in placentas and newborn babies.“But the study that really scared everyone found microplastics in human blood,” Emili said. That study, published in May 2022, was the first to detect microplastics in human blood. They showed up in 80% of people who were tested.“This means we’re starting to see not just ingestion of microplastics by animals and people, but also absorption of really, really small microplastics at a cellular level.”It’s not yet entirely known how having microplastics in our bodies and blood impacts our health, but other research suggests the pollution can damage human cells, while other scientists have hypothesized they could increase cancer risk and cause reproductive harm, among other health problems. And we do know that some of the toxic substances that piggyback on microplastics, like heavy metals, PFAS and endocrine-disrupting chemicals are associated with numerous health problems including higher cancer risk and reproductive harm.Researchers are also worried that an influx of microplastics in fresh water has the potential to disrupt natural carbon cycles, further fueling the climate crisis, according to Emili.“If we’re substituting plastics for something like natural sediment, microbes may gravitate toward them more than natural sources, which could upset the larger carbon sequestration cycle,” she explained. “We don’t know for sure, but this is also something we really need to look at.”

Plastic nurdle libraries

The groups doing nurdle patrol in the Ohio River are working with researchers at Penn State University to build a “nurdle library” — an index of the various nurdles they’ve collected with information about where each one came from and what it’s made of.These libraries could help them quickly identify large quantities of nurdles they spot down the line. But there are many potential sources for nurdles spills, and identifying where each piece of plastic came from poses its own challenges.“Nurdles start to degrade once they’re in the environment,” Emili explained. “The way they started out their life looking, chemically, is not necessarily what they’ll look like after degrading. That makes it harder to say for sure where they came from.”In May of 2022, a train derailment outside of Pittsburgh spilled approximately 120,000 pounds of plastic nurdles into the Allegheny River (along with approximately 5,723 pounds of oil). The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection oversaw cleanup efforts conducted by contractors for Norfolk Southern Corporation, the owner of the rail line responsible for the spill. The company estimated that 99% of the nurdles were recovered, according to the state agency, but the nurdle patrollers say they still regularly come across pieces of plastic they recognize from that spill. The company hasn’t yet been fined for the accident, and the activists worry that enforcement related to releases of nurdles is inadequate to deter them. “The cleanup of this incident is ongoing and [the Department of Environmental Protection] DEP is reviewing revised plans for how the operator will clean up remaining pellets,” the agency’s spokesperson Lauren Camarda told EHN. “The remediation and DEP’s compliance and enforcement activities related to this incident are ongoing, and, as such, DEP has not yet assessed a civil penalty.”A recent report by international conservation organization Fauna & Flora International noted that nurdle pollution isn’t something that can be controlled through individual consumers, and called for a “robust, coordinated regulatory approach from industry, governments, and the International Maritime Organization.”“So far we haven’t seen satisfactory enforcement even for egregious violations,” Evan Clark, a boat captain and nurdle patrol leader with Three Rivers Waterkeeper, told EHN. “We’re going to keep an eye on Styropek, but for us the bigger picture is making sure we can get our regulators to do meaningful enforcement around plastics in our waterways.”From Your Site ArticlesRelated Articles Around the Web

‘A drop in the ocean’: England bans some single-use plastics – but does it go far enough?

Single-use plastic items including cutlery and plates will soon be banned in England, the government has announced.Each year, the country uses around 1.1 billion single-use plates and 4.25 billion items of cutlery, according to government estimates. Only 10 per cent of these are recycled.Now, environment secretary Thérèse Coffey has confirmed that such items will be outlawed in England.Similar bans are already in place in Scotland and Wales.‘A plastic fork can take 200 years to decompose’Plastic objects used for takeaway food and drink – including containers, trays and cutlery – are the biggest polluters of the world’s oceans, studies have shown.“A plastic fork can take 200 years to decompose, that is two centuries in landfill or polluting our oceans,” says Coffey.Billions of single-use plastic items are disposed of each year in England, rather than recycled.England bans single use plasticEngland is now set to ban single-use items including plastic plates, knives and forks.The decision comes after a consultation by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) that took place from November 2021 to February 2022.“I am determined to drive forward action to tackle this issue head on,” Coffey says.“We’ve already taken major steps in recent years – but we know there is more to do, and we have again listened to the public’s calls.“This new ban will have a huge impact to stop the pollution of billions of pieces of plastic and help to protect the natural environment for future generations.”However, some campaigners have criticised the ban for its limited scope.“Whilst the removal of billions of commonly littered items is never a bad thing – this is a very long overdue move and still a drop in the ocean compared to the action that’s needed to stem the plastic tide,” tweeted Megan Randles, a political campaigner at Greenpeace UK.What items will be included in England’s single-use plastic ban?The government is yet to release details of the single-use plastic ban.On Saturday, more information will be announced about the objects included and where the ban will apply.The ruling will cover plastic plates, bowls and trays used for food items consumed in a restaurant or cafe, the Daily Mail reports, but not in environments like supermarkets and shops.What other European countries have banned single use plastic?A similar ban has already been introduced in Scotland and Wales. In England, single-use plastic straws, stirrers and cotton buds were outlawed in 2020.Green campaigners in England have criticised the government’s delay in bringing in the new measures.The country lags behind the EU, which introduced a ban on single-use plastic items in 2021. The ruling prohibits the sale of common pollutants including straws, plastic bottles, coffee cups and takeaway containers on EU markets.Although not in the EU, Norway also adopted the measures.Further proposals have recently been made to ban miniature hotel toiletries, among other items, as part of the European Green Deal’s fight against packaging waste.In Germany, plastic manufacturers will have to begin paying towards litter collections in 2025.

ClientEarth set to take Danone to court over its plastics footprint

Danone owns brands including evian, Volvic, Activia and Actimel The environmental law firm has today (9 January) confirmed its filing of a case at the Paris Tribunal Judiciaire, accusing Danone of flouting its requirements under the French Duty of Vigilance law. Danone has stated that it is “very surprised” by the move and “strongly refutes” ClientEarth’s claims.

This law was implemented in 2017. It requires large businesses headquartered in France to publish ‘vigilance’ plans each year, setting out the environmental and social risks and impacts of their operations, suppliers and subcontractors. The plan must be global in scope and cover all owned brands and subsidiaries. As well as identifying risks, plans have to include prevention and mitigation measures and information on how the company is implementing these measures and results delivered so far.

ClientEarth is arguing that, as a major plastic packaging producer and distributor, Danone should be obliged under this law to include measures on plastics pollution across the value chain. Danone sells products in more than 120 countries and, according to Break Free From Plastic, is one of the world’s ten largest plastic packaging producers. The campaign also dubbed Danone the top plastic polluter in Indonesia.

In announcing the case, ClientEarth does acknowledge that Danone has implemented a plan relating to plastics. However, it criticizes the corporate’s decision to focus on recycling after consumer use., citing stagnating plastic recycling rates in major economies in the Global North and poor recycling infrastructure development in the Global South. Danone is targeting 100% recyclable or reusable packaging by 2025 and its latest annual report reveals that a proportion of 81% has been achieved.

“Recycling is a limited solution as only 9% of plastics ever made have been recycled,” said ClientEarth’s plastics lawyer Rosa Pritchard. “It’s unrealistic for food giants like Danone to pretend recycling is the silver bullet.”

Without adequate recycling, ClientEarth is arguing, plastics pose an array of environmental risks. These include emissions associated with landfilling, dumping and burning, plus the impact of plastic pollution on nature and human health. Research is ever-evolving on this latter topic. One recent study at the University of Hull found that members of the general public are ingesting microplastics “at levels consistent with harmful effects on cells, which are in many cases the initiative event for health effects”. Effects include disruption to hormone imbalance, organ inflammation and allergic reactions.

ClientEarth also mentions the social impact of plastics. This includes exposure to chemicals in the production process and informal waste management space, particularly in low-income nations.

ClientEarth is asking Danone to measure its plastic use across the value chain, including logistics and promotions. It then wants Danone to map the impact that plastics have on the environment and on humanity across its entire value chain.

From there, the company would be able to update its plastic plan. ClientEarth wants a commitment to reduce absolute plastic use over time.

These measures could be forced by a court intervention or agreed upon outside of court. The court will decide when to hold an initial hearing in the coming weeks and will likely set a date in the first half of the year if it does decide that a lawsuit should be opened.

Supporting ClientEarth with this case are the non-profit Surfrider and NGO Zero Waste France.

Danone’s response

edie approached Danone for a comment. A spokesperson said: “We are very surprised by this accusation, which we strongly refute. Danone has long been recognized as a pioneer in environmental risk management, and we remain fully committed and determined to act responsibly.”

The spokesperson went on to call Danone’s plastics targets “comprehensive”, covering reuse, recycling and alternative materials. They also noted Danone’s support of strong international agreements, through the UN, on a new plastics treaty: “Putting an end to plastic pollution cannot come from one single company and requires the mobilisation of all players, public and industrial, while respecting the imperatives of food safety. This is why we support the adoption, under the aegis of the UN, of a legally binding international treaty.”

Negotiators have until 2024 to finalise the treaty, following agreement on the broad terms last year.

Published 9th January 2023

© Faversham House Ltd 2023 edie news articles may be copied or forwarded for individual use only. No other reproduction or distribution is permitted without prior written consent.

Study: Most farmers recycle plastic waste, but burning persists

A new study has found that the majority of farmers recycle agricultural plastic waste, but illegal burning and burying still persists on some farms.

The survey of 430 farmers on their attitudes towards the disposal and management of agricultural plastic is part of current PhD research on microplastics in soils being carried out by Clodagh King at Dundalk Institute of Technology (DkIT).

The research, which also examined farmers’ awareness and perceptions of the impacts of microplastics and plastics on the environment, was recently published in the internationally-respected journal, Science of the Total Environment (STOTEN).

Clodagh King

Over 88% of farmers who took part in the survey said that they are concerned about the amount of plastic waste generated by agricultural activities.

Most farmers view agricultural plastics negatively because of their environmental impact, along with the cost and logistics involved in dealing with them.

The study concluded that most farmers recycle their agricultural plastic.

The rate of recycling carried out by farmers was dependent on a number of factors including the type of plastic involved, the cost of recycling, access to facilities and knowledge about what can be recycled.

However, some farmers “openly admitted” to burning and burial of plastic waste on their farms, which is not only illegal but damaging to the environment.

The researchers recommended that initiatives should be rolled out to educate farmers on how to recycle farm plastics properly.

Plastic waste

Large pieces of plastic which are not properly managed can disintegrate into microplastics and make their way into soils, surface and groundwater sources.

Around 58% of farmers were “relatively aware” of microplastic pollution, but overall felt that they were more knowledgeable about plastic pollution.

More farmers also believed that aquatic environments are at greater risk to plastic pollution than the terrestrial environments.

Clodagh King in the laboratory at DkIT

The study, led by Clodagh King, recommended that future research efforts must focus on plastic and microplastic pollutions in soils to inform policy and to create greater public awareness of this issue.

It also outlined that new research is needed into the economic and practical viability of biobased and biodegradable plastics for use in agriculture.

“The findings from our study suggest that combined efforts by governments, policy makers, and other stakeholders must be undertaken to reduce the plastic and microplastic problem, it’s an environmental problem that we collectively must come together to solve,” King said.

In Iceland, start-up founders invent new ways to tackle environmental crises

REYKJANES PENINSULA, Iceland — The electric red and green glow of the production facility resembles the Icelandic aurora borealis. Algae in their growth stage flow through hundreds of glass tubes that travel from floor to ceiling, all part of a multistep process yielding nutrients for health supplements. Soon, all parts of each alga will be used.The facility, operated by Icelandic manufacturer Algalif, is a space of inspiration for Julie Encausse, a 34-year-old bioplastic entrepreneur. During a July summer storm, Svavar Halldorsson, an Algalif executive, was guiding her through a tour of the company’s newest facility on the Reykjanes Peninsula.By the end of 2023, this new facility aims to triple its production. After Algalif dries the microalgae and extracts oleoresin, a third of this output then goes toward health supplements. Algalif has traditionally used the rest as a fertilizer. Now Encausse, founder and chief executive of the bioplastic start-up Marea, hopes to use that leftover biomass to create a microalgae spray that can reduce the world’s reliance on plastic packaging.Her newest partnership with Algalif is part of a start-up network in Iceland that focuses on inventive and creative technologies to address the climate and sustainability crisis. The Sjavarklasinn (“Iceland Ocean Cluster”) network includes environmental entrepreneurs working across several industries.Thor Sigfusson founded the network in 2012 after conducting research on how partnerships between companies in Iceland’s technology sector helped expand that industry. At the time, he found that the fishing industry was not experiencing the same collaboration or growth.“Even though companies were in the same building together, fishing from the same quotas and facing similar challenges, they were closed off,” said Alexandra Leeper, the Iceland Ocean Cluster’s head of research and innovation.Three cod hanging on the wall of the second-floor entryway are the first thing to greet any visitor to the Iceland Ocean Cluster. Lightbulbs shine from their centers, and the dried scales filter the light to fill the space with an amber glow. The precise design is one that underlines the group’s belief that using 100 percent of a fish or natural resource can give rise to innovative technologies.Straddling the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Iceland experiences dramatic seasons in an ever-changing geologic theater. Glaciers sit atop active volcano zones — the island exists in the extremes. This also means that Icelanders face daily indicators of climate change, such as increased glacial runoff.These visible impacts have given a heightened urgency to tackling environmental problems, fueling partnerships like the one between Encausse and Halldorsson.“It will all work out in the end,” Encausse says to a rain-drenched Algalif employee in passing as she and Halldorsson discuss the facility’s building timeline. In Icelandic, this is a common phrase — “þetta reddast” — that people use to assure one another.Learning to use all parts of a resourceEncausse and Marea co-founder Edda Bjork Bolladottir have partnered with the cluster for 2½ years. Encausse says that involvement was core to their company’s inception.“There is a collaborative mind-set when being on an island,” she said. “We need to work together to survive, and this was passed from generation to generation.”In a country about the size of Kentucky, the people of Iceland have had to learn how to guard their resources. Encausse has discovered that often means using 100 percent of any material — a lesson she’s now implementing in her work with Algalif. She created a food coating from Algalif’s leftover biomass, a product she’s named Iceborea — in a nod to the aurora borealis.“We are repurposing it and making something with value that gives it another life to avoid using more plastic,” Encausse said. Once Algalif’s factory expands over the next year, it will have 66 tons of microalgae leftovers that Encausse’s company can tap each year.When sprayed onto fresh produce, Iceborea becomes a natural thin film and a semipermeable barrier that can protect against microorganisms. Iceborea can either be eaten with produce or washed off, reducing the need for plastic packaging.Female founders in the clusterReusing factory byproducts is an entrepreneurial trend in Iceland.Take Edda Aradottir. She is the chief executive of Carbfix, a company capturing CO2 byproduct from the largest geothermal plant in Iceland, Hellisheidi, and injecting it into stone to be buried underground.Carbfix’s successful trials have marked a global milestone for carbon sequestration. It also has received international recognition — and Aradottir’s leadership has already served as a model for growing start-ups and other founders in the cluster trying to tackle extensive environmental concerns.“It’s inspiring to see that perseverance pays off,” Encausse said about Aradottir’s work.Another Icelandic company, GeoSilica, harvests silica buildup from the Hellisheidi waste stream to make health supplements. GeoSilica reaches the Icelandic and European markets, and its chief executive, Fida Abu Libdeh, is also working with the Philippines to pilot her silica-removal technology to create similar sustainable factory processes.A Palestinian from Jerusalem, Abu Libdeh moved to Iceland in 1995 at age 16, a transition she described as difficult because of the language barrier and the country’s small immigrant population. In 2012, she graduated from the University of Iceland after studying sustainable energy engineering and researching the health benefits of silica. That same year, she and Burkni Palsson co-founded GeoSilica.Ever since moving to Iceland, she was impressed with how the country produced electricity through geothermal sources.“I knew I was going to do something in connection with that in the future,” she said.GeoSilica is not formally part of the Iceland Ocean Cluster, but the network it has fostered reflects the same collaborative approach. Abu Libdeh has worked with cluster companies and held investor meetings at its headquarters. It’s a place that founders want to be, she said, where they want to learn from each other even if they are competitors in their fields.While there has been progress over the years, Abu Libdeh said, it’s still a challenge for women to enter this entrepreneurial space. In 2020, less than 1 percent of investment went to women-founded start-ups, according to a recent European Women in Venture Capital report.Halla Jonsdottir, research and development lead and co-founder of Optitog, has based her start-up in the cluster for three years. Her company is creating equipment to increase the catch area of shrimp trawls without scraping the seafloor — technology that’s meant to reduce fuel demands and CO2 emissions while protecting the ocean floor.As a female founder in the Icelandic fishing technology industry, Jonsdottir is a rarity. Leeper believes Jonsdottir may be one of the few women working in fishing gear innovation.Jonsdottir says the cluster helped drive her growth. “They put emphasis on making us visible in a male-driven industry.”Beyond IcelandWhat began as a dozen start-ups in 2012 has now grown to more than 70 members and associated firms connected to the Iceland Ocean Cluster. Sigfusson has ignited the blue economy within Iceland, but his project’s reach has also gone global.There are now four sister clusters in the United States, as well as one in Denmark and one in the Faroe Islands.The Alaska Ocean Cluster, which was the first to follow the Icelandic model, has already accelerated policy change in the United States. Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) proposed legislation last year to create “Ocean Innovation Clusters” in major U.S. port cities, which would provide grants along the U.S. coastline and the Great Lakes.“I’ve learned a great deal from our friends in Iceland who created a roadmap of innovation and public/private partnership when they established the first Oceans Cluster in Reykjavik,” Murkowski said in an email. “I’ll continue to press upon my colleagues the significance of this legislation and the promise it holds for the modernization and resilience of our maritime economy.”Back at the cluster houseAt 12:30 p.m. on a July afternoon, the cluster’s first-floor food hall, Grandi Matholl, buzzes during a busy hour. Fish haulers dressed in oversized, waterproof waders eat on wooden benches alongside employees in professional suits. Attached to the Matholl is Bakkaskemman, a seating area with a glass window where visitors can watch fish being unloaded off ships. Every afternoon on a business day, there’s an online auction to sell the day’s catch.Upstairs in her office, Jonsdottir works on her trawler technology. Later in the week, Encausse will use the meeting room space to meet with investors about Iceborea.The pungent smell of cod lingers in Bakkaskemman. It’s etched into the paint, leaking from the histories of the walls. In 30 minutes, the auction will begin.Sign up for the latest news about climate change, energy and the environment, delivered every Thursday