Single-use plastic items including cutlery and plates will soon be banned in England, the government has announced.Each year, the country uses around 1.1 billion single-use plates and 4.25 billion items of cutlery, according to government estimates. Only 10 per cent of these are recycled.Now, environment secretary Thérèse Coffey has confirmed that such items will be outlawed in England.Similar bans are already in place in Scotland and Wales.‘A plastic fork can take 200 years to decompose’Plastic objects used for takeaway food and drink – including containers, trays and cutlery – are the biggest polluters of the world’s oceans, studies have shown.“A plastic fork can take 200 years to decompose, that is two centuries in landfill or polluting our oceans,” says Coffey.Billions of single-use plastic items are disposed of each year in England, rather than recycled.England bans single use plasticEngland is now set to ban single-use items including plastic plates, knives and forks.The decision comes after a consultation by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) that took place from November 2021 to February 2022.“I am determined to drive forward action to tackle this issue head on,” Coffey says.“We’ve already taken major steps in recent years – but we know there is more to do, and we have again listened to the public’s calls.“This new ban will have a huge impact to stop the pollution of billions of pieces of plastic and help to protect the natural environment for future generations.”However, some campaigners have criticised the ban for its limited scope.“Whilst the removal of billions of commonly littered items is never a bad thing – this is a very long overdue move and still a drop in the ocean compared to the action that’s needed to stem the plastic tide,” tweeted Megan Randles, a political campaigner at Greenpeace UK.What items will be included in England’s single-use plastic ban?The government is yet to release details of the single-use plastic ban.On Saturday, more information will be announced about the objects included and where the ban will apply.The ruling will cover plastic plates, bowls and trays used for food items consumed in a restaurant or cafe, the Daily Mail reports, but not in environments like supermarkets and shops.What other European countries have banned single use plastic?A similar ban has already been introduced in Scotland and Wales. In England, single-use plastic straws, stirrers and cotton buds were outlawed in 2020.Green campaigners in England have criticised the government’s delay in bringing in the new measures.The country lags behind the EU, which introduced a ban on single-use plastic items in 2021. The ruling prohibits the sale of common pollutants including straws, plastic bottles, coffee cups and takeaway containers on EU markets.Although not in the EU, Norway also adopted the measures.Further proposals have recently been made to ban miniature hotel toiletries, among other items, as part of the European Green Deal’s fight against packaging waste.In Germany, plastic manufacturers will have to begin paying towards litter collections in 2025.

Category Archives: Plastic Pollution Articles & News

ClientEarth set to take Danone to court over its plastics footprint

Danone owns brands including evian, Volvic, Activia and Actimel The environmental law firm has today (9 January) confirmed its filing of a case at the Paris Tribunal Judiciaire, accusing Danone of flouting its requirements under the French Duty of Vigilance law. Danone has stated that it is “very surprised” by the move and “strongly refutes” ClientEarth’s claims.

This law was implemented in 2017. It requires large businesses headquartered in France to publish ‘vigilance’ plans each year, setting out the environmental and social risks and impacts of their operations, suppliers and subcontractors. The plan must be global in scope and cover all owned brands and subsidiaries. As well as identifying risks, plans have to include prevention and mitigation measures and information on how the company is implementing these measures and results delivered so far.

ClientEarth is arguing that, as a major plastic packaging producer and distributor, Danone should be obliged under this law to include measures on plastics pollution across the value chain. Danone sells products in more than 120 countries and, according to Break Free From Plastic, is one of the world’s ten largest plastic packaging producers. The campaign also dubbed Danone the top plastic polluter in Indonesia.

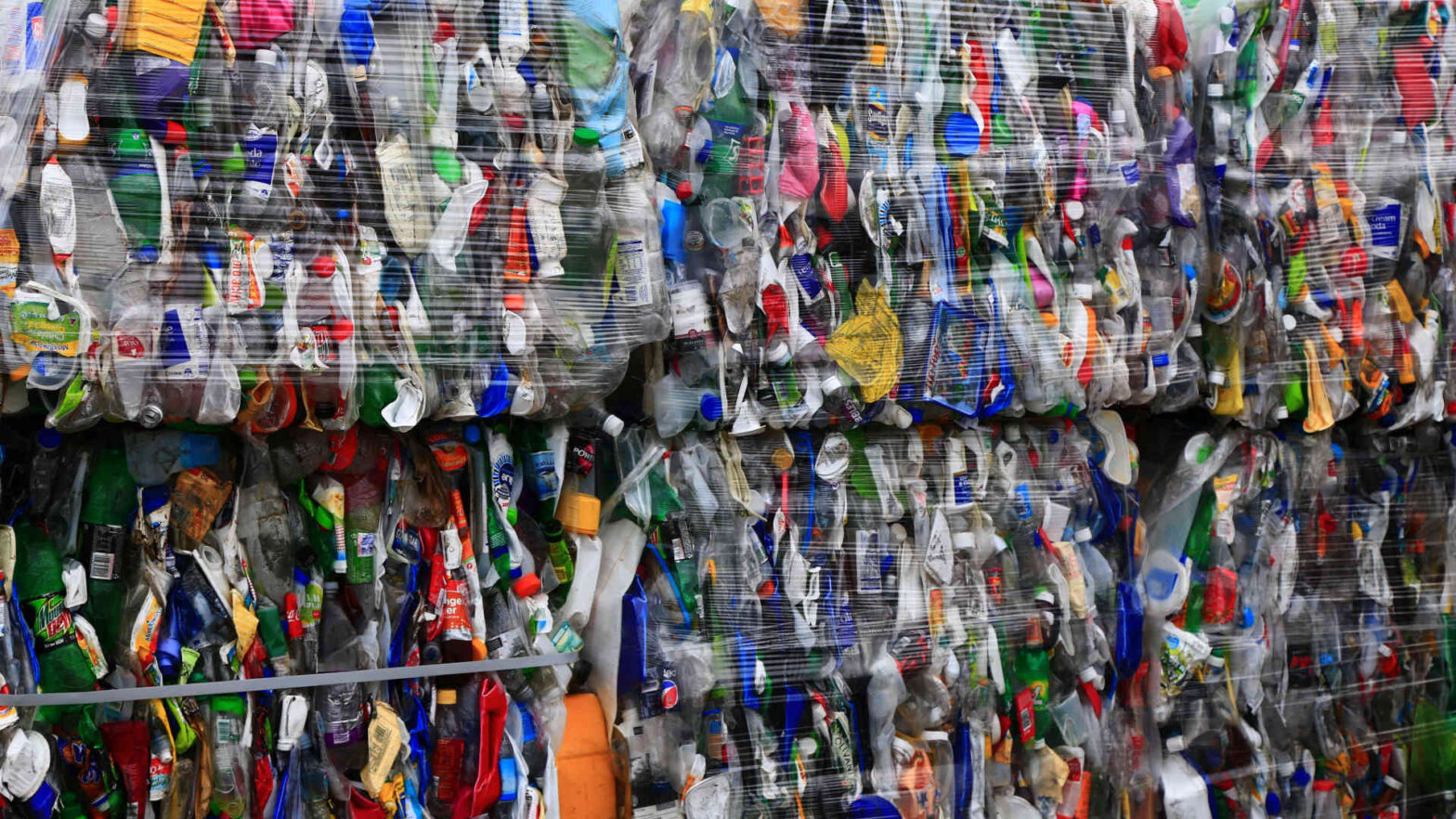

In announcing the case, ClientEarth does acknowledge that Danone has implemented a plan relating to plastics. However, it criticizes the corporate’s decision to focus on recycling after consumer use., citing stagnating plastic recycling rates in major economies in the Global North and poor recycling infrastructure development in the Global South. Danone is targeting 100% recyclable or reusable packaging by 2025 and its latest annual report reveals that a proportion of 81% has been achieved.

“Recycling is a limited solution as only 9% of plastics ever made have been recycled,” said ClientEarth’s plastics lawyer Rosa Pritchard. “It’s unrealistic for food giants like Danone to pretend recycling is the silver bullet.”

Without adequate recycling, ClientEarth is arguing, plastics pose an array of environmental risks. These include emissions associated with landfilling, dumping and burning, plus the impact of plastic pollution on nature and human health. Research is ever-evolving on this latter topic. One recent study at the University of Hull found that members of the general public are ingesting microplastics “at levels consistent with harmful effects on cells, which are in many cases the initiative event for health effects”. Effects include disruption to hormone imbalance, organ inflammation and allergic reactions.

ClientEarth also mentions the social impact of plastics. This includes exposure to chemicals in the production process and informal waste management space, particularly in low-income nations.

ClientEarth is asking Danone to measure its plastic use across the value chain, including logistics and promotions. It then wants Danone to map the impact that plastics have on the environment and on humanity across its entire value chain.

From there, the company would be able to update its plastic plan. ClientEarth wants a commitment to reduce absolute plastic use over time.

These measures could be forced by a court intervention or agreed upon outside of court. The court will decide when to hold an initial hearing in the coming weeks and will likely set a date in the first half of the year if it does decide that a lawsuit should be opened.

Supporting ClientEarth with this case are the non-profit Surfrider and NGO Zero Waste France.

Danone’s response

edie approached Danone for a comment. A spokesperson said: “We are very surprised by this accusation, which we strongly refute. Danone has long been recognized as a pioneer in environmental risk management, and we remain fully committed and determined to act responsibly.”

The spokesperson went on to call Danone’s plastics targets “comprehensive”, covering reuse, recycling and alternative materials. They also noted Danone’s support of strong international agreements, through the UN, on a new plastics treaty: “Putting an end to plastic pollution cannot come from one single company and requires the mobilisation of all players, public and industrial, while respecting the imperatives of food safety. This is why we support the adoption, under the aegis of the UN, of a legally binding international treaty.”

Negotiators have until 2024 to finalise the treaty, following agreement on the broad terms last year.

Published 9th January 2023

© Faversham House Ltd 2023 edie news articles may be copied or forwarded for individual use only. No other reproduction or distribution is permitted without prior written consent.

Study: Most farmers recycle plastic waste, but burning persists

A new study has found that the majority of farmers recycle agricultural plastic waste, but illegal burning and burying still persists on some farms.

The survey of 430 farmers on their attitudes towards the disposal and management of agricultural plastic is part of current PhD research on microplastics in soils being carried out by Clodagh King at Dundalk Institute of Technology (DkIT).

The research, which also examined farmers’ awareness and perceptions of the impacts of microplastics and plastics on the environment, was recently published in the internationally-respected journal, Science of the Total Environment (STOTEN).

Clodagh King

Over 88% of farmers who took part in the survey said that they are concerned about the amount of plastic waste generated by agricultural activities.

Most farmers view agricultural plastics negatively because of their environmental impact, along with the cost and logistics involved in dealing with them.

The study concluded that most farmers recycle their agricultural plastic.

The rate of recycling carried out by farmers was dependent on a number of factors including the type of plastic involved, the cost of recycling, access to facilities and knowledge about what can be recycled.

However, some farmers “openly admitted” to burning and burial of plastic waste on their farms, which is not only illegal but damaging to the environment.

The researchers recommended that initiatives should be rolled out to educate farmers on how to recycle farm plastics properly.

Plastic waste

Large pieces of plastic which are not properly managed can disintegrate into microplastics and make their way into soils, surface and groundwater sources.

Around 58% of farmers were “relatively aware” of microplastic pollution, but overall felt that they were more knowledgeable about plastic pollution.

More farmers also believed that aquatic environments are at greater risk to plastic pollution than the terrestrial environments.

Clodagh King in the laboratory at DkIT

The study, led by Clodagh King, recommended that future research efforts must focus on plastic and microplastic pollutions in soils to inform policy and to create greater public awareness of this issue.

It also outlined that new research is needed into the economic and practical viability of biobased and biodegradable plastics for use in agriculture.

“The findings from our study suggest that combined efforts by governments, policy makers, and other stakeholders must be undertaken to reduce the plastic and microplastic problem, it’s an environmental problem that we collectively must come together to solve,” King said.

In Iceland, start-up founders invent new ways to tackle environmental crises

REYKJANES PENINSULA, Iceland — The electric red and green glow of the production facility resembles the Icelandic aurora borealis. Algae in their growth stage flow through hundreds of glass tubes that travel from floor to ceiling, all part of a multistep process yielding nutrients for health supplements. Soon, all parts of each alga will be used.The facility, operated by Icelandic manufacturer Algalif, is a space of inspiration for Julie Encausse, a 34-year-old bioplastic entrepreneur. During a July summer storm, Svavar Halldorsson, an Algalif executive, was guiding her through a tour of the company’s newest facility on the Reykjanes Peninsula.By the end of 2023, this new facility aims to triple its production. After Algalif dries the microalgae and extracts oleoresin, a third of this output then goes toward health supplements. Algalif has traditionally used the rest as a fertilizer. Now Encausse, founder and chief executive of the bioplastic start-up Marea, hopes to use that leftover biomass to create a microalgae spray that can reduce the world’s reliance on plastic packaging.Her newest partnership with Algalif is part of a start-up network in Iceland that focuses on inventive and creative technologies to address the climate and sustainability crisis. The Sjavarklasinn (“Iceland Ocean Cluster”) network includes environmental entrepreneurs working across several industries.Thor Sigfusson founded the network in 2012 after conducting research on how partnerships between companies in Iceland’s technology sector helped expand that industry. At the time, he found that the fishing industry was not experiencing the same collaboration or growth.“Even though companies were in the same building together, fishing from the same quotas and facing similar challenges, they were closed off,” said Alexandra Leeper, the Iceland Ocean Cluster’s head of research and innovation.Three cod hanging on the wall of the second-floor entryway are the first thing to greet any visitor to the Iceland Ocean Cluster. Lightbulbs shine from their centers, and the dried scales filter the light to fill the space with an amber glow. The precise design is one that underlines the group’s belief that using 100 percent of a fish or natural resource can give rise to innovative technologies.Straddling the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Iceland experiences dramatic seasons in an ever-changing geologic theater. Glaciers sit atop active volcano zones — the island exists in the extremes. This also means that Icelanders face daily indicators of climate change, such as increased glacial runoff.These visible impacts have given a heightened urgency to tackling environmental problems, fueling partnerships like the one between Encausse and Halldorsson.“It will all work out in the end,” Encausse says to a rain-drenched Algalif employee in passing as she and Halldorsson discuss the facility’s building timeline. In Icelandic, this is a common phrase — “þetta reddast” — that people use to assure one another.Learning to use all parts of a resourceEncausse and Marea co-founder Edda Bjork Bolladottir have partnered with the cluster for 2½ years. Encausse says that involvement was core to their company’s inception.“There is a collaborative mind-set when being on an island,” she said. “We need to work together to survive, and this was passed from generation to generation.”In a country about the size of Kentucky, the people of Iceland have had to learn how to guard their resources. Encausse has discovered that often means using 100 percent of any material — a lesson she’s now implementing in her work with Algalif. She created a food coating from Algalif’s leftover biomass, a product she’s named Iceborea — in a nod to the aurora borealis.“We are repurposing it and making something with value that gives it another life to avoid using more plastic,” Encausse said. Once Algalif’s factory expands over the next year, it will have 66 tons of microalgae leftovers that Encausse’s company can tap each year.When sprayed onto fresh produce, Iceborea becomes a natural thin film and a semipermeable barrier that can protect against microorganisms. Iceborea can either be eaten with produce or washed off, reducing the need for plastic packaging.Female founders in the clusterReusing factory byproducts is an entrepreneurial trend in Iceland.Take Edda Aradottir. She is the chief executive of Carbfix, a company capturing CO2 byproduct from the largest geothermal plant in Iceland, Hellisheidi, and injecting it into stone to be buried underground.Carbfix’s successful trials have marked a global milestone for carbon sequestration. It also has received international recognition — and Aradottir’s leadership has already served as a model for growing start-ups and other founders in the cluster trying to tackle extensive environmental concerns.“It’s inspiring to see that perseverance pays off,” Encausse said about Aradottir’s work.Another Icelandic company, GeoSilica, harvests silica buildup from the Hellisheidi waste stream to make health supplements. GeoSilica reaches the Icelandic and European markets, and its chief executive, Fida Abu Libdeh, is also working with the Philippines to pilot her silica-removal technology to create similar sustainable factory processes.A Palestinian from Jerusalem, Abu Libdeh moved to Iceland in 1995 at age 16, a transition she described as difficult because of the language barrier and the country’s small immigrant population. In 2012, she graduated from the University of Iceland after studying sustainable energy engineering and researching the health benefits of silica. That same year, she and Burkni Palsson co-founded GeoSilica.Ever since moving to Iceland, she was impressed with how the country produced electricity through geothermal sources.“I knew I was going to do something in connection with that in the future,” she said.GeoSilica is not formally part of the Iceland Ocean Cluster, but the network it has fostered reflects the same collaborative approach. Abu Libdeh has worked with cluster companies and held investor meetings at its headquarters. It’s a place that founders want to be, she said, where they want to learn from each other even if they are competitors in their fields.While there has been progress over the years, Abu Libdeh said, it’s still a challenge for women to enter this entrepreneurial space. In 2020, less than 1 percent of investment went to women-founded start-ups, according to a recent European Women in Venture Capital report.Halla Jonsdottir, research and development lead and co-founder of Optitog, has based her start-up in the cluster for three years. Her company is creating equipment to increase the catch area of shrimp trawls without scraping the seafloor — technology that’s meant to reduce fuel demands and CO2 emissions while protecting the ocean floor.As a female founder in the Icelandic fishing technology industry, Jonsdottir is a rarity. Leeper believes Jonsdottir may be one of the few women working in fishing gear innovation.Jonsdottir says the cluster helped drive her growth. “They put emphasis on making us visible in a male-driven industry.”Beyond IcelandWhat began as a dozen start-ups in 2012 has now grown to more than 70 members and associated firms connected to the Iceland Ocean Cluster. Sigfusson has ignited the blue economy within Iceland, but his project’s reach has also gone global.There are now four sister clusters in the United States, as well as one in Denmark and one in the Faroe Islands.The Alaska Ocean Cluster, which was the first to follow the Icelandic model, has already accelerated policy change in the United States. Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) proposed legislation last year to create “Ocean Innovation Clusters” in major U.S. port cities, which would provide grants along the U.S. coastline and the Great Lakes.“I’ve learned a great deal from our friends in Iceland who created a roadmap of innovation and public/private partnership when they established the first Oceans Cluster in Reykjavik,” Murkowski said in an email. “I’ll continue to press upon my colleagues the significance of this legislation and the promise it holds for the modernization and resilience of our maritime economy.”Back at the cluster houseAt 12:30 p.m. on a July afternoon, the cluster’s first-floor food hall, Grandi Matholl, buzzes during a busy hour. Fish haulers dressed in oversized, waterproof waders eat on wooden benches alongside employees in professional suits. Attached to the Matholl is Bakkaskemman, a seating area with a glass window where visitors can watch fish being unloaded off ships. Every afternoon on a business day, there’s an online auction to sell the day’s catch.Upstairs in her office, Jonsdottir works on her trawler technology. Later in the week, Encausse will use the meeting room space to meet with investors about Iceborea.The pungent smell of cod lingers in Bakkaskemman. It’s etched into the paint, leaking from the histories of the walls. In 30 minutes, the auction will begin.Sign up for the latest news about climate change, energy and the environment, delivered every Thursday

Volume of microplastics found on ocean floor triple in two decades

Sign up to the Independent Climate email for the latest advice on saving the planet Get our free Climate email Microplastic debris found on the bottom of ocean beds has tripled in the past two decades, scientists have warned. That is despite repeated awareness campaigns and protests calling for the reduction of single-use plastic around …

Continue reading “Volume of microplastics found on ocean floor triple in two decades”

How microplastics are infiltrating the food you eat

Plastic pollution is one of the defining legacies of our modern way of life, but it is now so widespread it is even finding its way into fruit and vegetables as they grow.Microplastics have infiltrated every part of the planet. They have been found buried in Antarctic sea ice, within the guts of marine animals inhabiting the deepest ocean trenches, and in drinking water around the world. Plastic pollution has been found on beaches of remote, uninhabited islands and it shows up in sea water samples across the planet. One study estimated that there are around 24.4 trillion fragments of microplastics in the upper regions of the world’s oceans.

But they aren’t just ubiquitous in water – they are spread widely in soils on land too and can even end up in the food we eat. Unwittingly, we may be consuming tiny fragments of plastic with almost every bite we take.

In 2022, analysis by the Environmental Working Group, an environmental non-profit, found that sewage sludge has contaminated almost 20 million acres (80,937sq km) of US cropland with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), often called “forever chemicals”, which are commonly found in plastic products and do not break down under normal environmental conditions.

Sewage sludge is the byproduct left behind after municipal wastewater is cleaned. As it is expensive to dispose of and rich in nutrients, sludge is commonly used as organic fertiliser in the US and Europe. In the latter, this is in part due to EU directives promoting a circular waste economy. An estimated 8-10 million tonnes of sewage sludge is produced in Europe each year, and roughly 40% of this is spread on farmland.

Due to this practice, European farmland could be the biggest global reservoir of microplastics, according to a study by researchers at Cardiff University. This means between 31,000 and 42,000 tonnes of microplastics, or 86 trillion to 710 trillion microplastic particles, contaminate European farmland each year.Spreading sewage sludge, or bio-solids, onto fields is common practice in many parts of the world (Credit: RJ Sangosti/The Denver Post/Getty Images)The researchers found that up to 650 million microplastic particles, measuring between 1mm and 5mm (0.04in-0.2in), entered one wastewater treatment plant in south Wales, in the UK, every day. All these particles ended up in the sewage sludge, making up roughly 1% of the total weight, rather than being released with the clean water.

The number of microplastics that end up on farmland “is probably an underestimation,” says Catherine Wilson, one of the study’s co-authors and deputy director of the Hydro-environmental Research Centre at Cardiff University. “Microplastics are everywhere and [often] so tiny that we can’t see them.”SENSORY OVERLOADFrom the microplastics sprayed on farmland to the noxious odours released by sewage plants and the noise harming marine life, pollutants are seeping into every aspect of our existence. Sensory Overload explores the impact of pollution on all our senses and the long-term harm it is inflicting on humans and the natural world. Read some of the other stories from the series here:

The underwater sounds that can kill

And microplastics can stay there for a long time too. One recent study by soil scientists at Philipps-University Marburg found microplastics up to 90cm (35in) below the surface on two agricultural fields where sewage sludge had last been applied 34 years ago. Ploughing also caused the plastic to spread into areas where the sludge had not been applied.

The microplastics’ concentration on farmland soils in Europe is similar to the amount found in ocean surface waters, says James Lofty, the lead author of the Cardiff study and a PhD research student at the Hydro-environmental Research Centre.

The UK has some of the highest concentrations of microplastics in Europe, with between 500 and 1,000 microplastic particles are spread on farmland there each year, according to Wilson and Lofty’s research.

As well as creating a large reservoir of microplastics on land, the practice of using sewage sludge as fertiliser is also exacerbating the plastics crisis in our oceans, adds Lofty. Eventually the microplastics will end up in waterways, as rain washes the top layer of soil into rivers or washes them into groundwater. “The major source of [plastic] contamination in our rivers and oceans is from runoff,” he says.

One study by researchers in Ontario, Canada, found that 99% of microplastics were transported away from where the sludge was initially dumped into aquatic environments.

Environmental contamination

Before they are washed away, however, microplastics can leach toxic chemicals into the soil. Not only are they made from potentially harmful chemicals that can be released into the environment as they break down, microplastics can also absorb other toxic substances, essentially allowing them to hitch a ride onto agricultural land where they can leach into the soil, according to Lofty.Tiny fragments of plastics – from clothing, cosmetics or larger plastics that break down – can get into water supplies and soil easily (Credit: Aris Messinis/AFP/Getty Images)A report by the UK’s Environment Agency, which was subsequently revealed by the environmental campaign group Greenpeace, found that sewage waste destined for English farmland was contaminated with pollutants including dioxins and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at “levels that may present a risk to human health”.

A 2020 experiment by Kansas University agronomist Mary Beth Kirkham found that plastic serves as a vector for plant uptake of toxic chemicals such as cadmium. “In the plants where cadmium was in the soil with plastic, the wheat leaves had much, much more cadmium than in the plants that grew without plastic in the soil,” Kirkham said at the time.

Research also shows that microplastics can stunt the growth of earthworms and cause them to lose weight. The reasons for this weight loss aren’t fully understood, but one theory is that microplastics may obstructs earthworms’ digestive tracts, limiting their ability to absorb nutrients and so limiting their growth. This has a negative impact on the wider environment, too, the researchers say, as earthworms play a vital role in maintaining soil health. Their burrowing activity aerates the soil, prevents erosion, improves water drainage and recycles nutrients.

Plastic particles can also contaminate food crops directly. A 2020 study found microplastics and nanoplastics in fruit and vegetables sold by supermarkets and in produce sold by local sellers in Catania in Sicily, Italy. Apples were the most contaminated fruit, and carrots had the highest levels of microplastics among the sampled vegetables.

According to research by Willie Peijnenburg, professor of environmental toxicology and biodiversity at Leiden University in the Netherlands, crops absorb nanoplastic particles – minuscule fragments measuring between 1-100nm in size, or about 1,000 to 100 times smaller than a human blood cell – from surrounding water and soil through tiny cracks in their roots.

Analysis revealed that most of the plastics accumulated in the plant roots, with only a very small amount travelling up to the shoots. “Concentrations in the leaves are well below 1%,” says Peijnenburg. For leafy vegetables such as lettuces and cabbage, the concentrations of plastic would likely then be relatively low, but for root vegetables such as carrots, radishes and turnips, the risk of consuming microplastics would be greater, he warns.

Another study by Peijnenburg and his colleagues found that in both lettuce and wheat, the concentration of microplastics was 10 times lower than in the surrounding soil. “We found that only the smallest particles are taken up by the plants and the big ones are not,” says Peijnenburg.

This is reassuring, says Peijnenburg. However, many microplastics will slowly degrade and break down into nanoparticles, providing a “good source for plant uptake,” he adds.The uptake of the plastic particles did not seem to stunt the growth of the crops, according to Peijnenburg’s research. But what effect this accumulation of plastic in our food has on our own health is less clear.

Further research is needed to understand this, says Peijnenburg, especially as the problem will only get bigger.

“It will take decades before plastics are fully removed from the environment,” he says. “Even if the risk is currently not very high, it’s not a good idea to have persistent chemicals [on farmland]. They will pile up and then they might form a risk.”

Health impacts

While the impact of ingesting plastics on human health is not yet fully understood, there is already some research that suggests it could be harmful. Studies show that chemicals added during the production of plastics can disrupt the endocrine system and the hormones that regulate our growth and development.

Chemicals found in plastic have been linked to a range of other health problems including cancer, heart disease and poor foetal development. High levels of ingested microplastics may also cause cell damage which could lead to inflammation and allergic reactions, according to analysis by researchers at the University of Hull, in the UK.

The researchers reviewed 17 previous studies which looked at the toxicological impact of microplastics on human cells. The analysis compared the amount of microplastics that caused damage to cells in laboratory tests with the levels ingested by people through drinking water, seafood and salt. It found that the amounts being ingested approached those that could trigger cell death, but could also cause immune responses, including allergic reactions, damage to cell walls, and oxidative stress.

“Our research shows that we are ingesting microplastics at the levels consistent with harmful effects on cells, which are in many cases the initiating event for health effects,” says Evangelos Danopoulos, lead author of the study and a researcher at Hull York Medical School. “We know that microplastics can cross the barriers of cells and also break them, We know they can also cause oxidative stress on cells, which is the start of tissue damage.”Plastic fragments appear to accumulate most in the roots of plants, which is particularly problematic for tuber and root vegetables (Credit: Yuji Sakai/Getty Images)There are two theories as to how microplastics lead to cell breakdown, says Danopoulos. Their sharp edges could rupture the cell wall or the chemicals in the microplastics could damage the cell, he says. The study found that irregularly-shaped microplastics were the most likely to cause cell death.

“What we now need to understand is how many microplastics remain in our body and what kind of size and shape is able to cross the cell barrier,” says Danopoulos. If plastics were to accumulate to the levels at which they could become harmful over a period of time, this could pose an even greater risk to human health.

But even without these answers, Danopoulos questions whether more care is needed to ensure microplastics do not enter the food chain. “If we know that sludge is contaminated with microplastics and that plants have the ability to extract them from the soil, should we be using it as fertiliser?” he says.

Banning sewage sludge

Spreading sludge on farmland has been banned in the Netherlands since 1995. The country initially incinerated the sludge, but started exporting it to the UK, where it was used as fertiliser on farmland, after problems at an Amsterdam incineration plant.

Switzerland prohibited the use of sewage sludge as fertiliser in 2003 because it “comprises a whole range of harmful substances and pathogenic organisms produced by industry and private households”. The US state Maine also banned the practice in April 2022 after environmental authorities found high levels of PFAS on farmland soil, crops and water. High PFAS levels were also detected in farmers’ blood. The widespread contamination forced several farms to close.

The new Maine law also forbids sludge from being composted with other organic material.

But a total ban on using sewage sludge as fertiliser is not necessarily the best solution, says Cardiff University’s Wilson. Instead, it could incentivise farmers to use more synthetic nitrogen fertilisers, made from natural gas, she says.

“[With sewage sludge], we’re using a waste product in an efficient way, rather than producing endless fossil fuel fertilisers,” says Wilson. The organic waste in sludge also helps return carbon to the soil and enriches it with nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, which prevents soil degradation, she says.”We need to quantify the microplastics in sewage sludge so that we can [determine] where the hot spots are and start managing it,” says Wilson. In places with high levels of microplastics, sewage sludge could be incinerated to generate energy instead of used as fertiliser, she suggests. One way to prevent the contamination of farmland is to recover fats, oil and grease (which contain high levels of microplastics) at wastewater treatment plants and use this “surface scum” as biofuel, instead of mixing it with sludge, Wilson and her colleagues say.

Some European countries, such as Italy and Greece, dispose of sewage sludge in landfill sites, the researchers note, but they warn that there is a risk of microplastics leaching into the environment from these sites and contaminating surrounding land and water bodies.

Both Wilson and Danopoulos say much more research is needed to quantify the amount of microplastics on farmland and the possible environmental and health impacts.

“Microplastics are now on the cusp of changing from a contaminant to a pollutant,” says Danopoulos. “A contaminant is something that is found where it shouldn’t be. Microplastics shouldn’t be in our water and soil. If we prove that [they have] adverse effects, that would make them a pollutant and [we] would have to bring in legislation and regulations.”

—

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

The steep cost of bio-based plastics

It’s the year 2050, and humanity has made huge progress in decarbonizing. That’s thanks in large part to the negligible price of solar and wind power, which was cratering even back in 2022. Yet the fossil fuel industry hasn’t just doubled down on making plastics from oil and gas — instead, as the World Economic Forum warned would happen, it has tripled production from 2016 levels. In 2050, humans are churning out trillions of pounds of plastic a year, and in the process emitting the greenhouse gas equivalent of over 600 coal-fired power plants. Three decades from now, we’ve stopped using so much oil and gas as fuel, yet way more of them as plastic.

Back here in 2022, people are trying to head off that nightmare scenario with a much-hyped concept called “bio-based plastics.” The backbones of traditional plastics are chains of carbon derived from fossil fuels. Bioplastics instead use carbon extracted from crops like corn or sugarcane, which is then mixed with other chemicals, like plasticizers, found in traditional plastics. Growing those plants pulls carbon out of the atmosphere and locks it inside the bioplastic — if it is used for a permanent purpose, like building materials, rather than single-use cups and bags.

This story was originally published by the Wired and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

At least, that’s the theory. In reality, bio-based plastics are problematic for a variety of reasons. It would take an astounding amount of land and water to grow enough plants to replace traditional plastics — plus energy is needed to produce and ship it all. Bioplastics can be loaded with the same toxic additives that make a plastic plastic, and still splinter into micro-sized bits that corrupt the land, sea, and air. And switching to bioplastics could give the industry an excuse to keep producing exponentially more polymers under the guise of “eco-friendliness,” when scientists and environmentalists agree that the only way to stop the crisis is to just stop producing so much damn plastic, whatever its source of carbon.

But let’s say there was a large-scale shift to bioplastics — what would that mean for future emissions? That’s what a new paper in the journal Nature set out to estimate, finding that if a slew of variables were to align — and that’s a very theoretical if — bioplastics could go carbon-negative.

The modeling considered four scenarios for how plastics production — and the life cycle of those products — might unfold through the year 2100, modeling even further out than those earlier predictions about production through 2050. The first scenario is a baseline, in which business continues as usual. The second adds a tax on CO2 emissions, which would make it more expensive to produce fossil-fuel plastics, encouraging a shift toward bio-based plastics and reducing emissions through the end of the century. (It would also incentivize using more renewable energy to produce plastic.) The third assumes the development of a more circular economy for plastics, making them more easily reused or recycled, reducing both emissions and demand. And the last scenario imagines a circular bio-economy, in which much more plastic has its roots in plants, and is used over and over.

“Here, we combine all of these: We have the CO2 price in place, we have circular economy strategies, but additionally we kind of push more biomass into the sector by giving it a certain subsidy,” says the study’s lead author, Paul Stegmann, who’s now at the Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research but did the work while at Utrecht University, in cooperation with PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. If all three conditions are met, he says, it is enough to push emissions into the negative.

It would take an astounding amount of land and water to grow enough plants to replace traditional plastics — plus energy is needed to produce and ship it all.

In this version of the future, people would still have to grow lots of crops to make bioplastics, but those plastics would be used — and reused — many times. “You basically put it into the system and keep it as long as possible,” says Stegmann.

To be clear, this is a hypothetical scenario, not a prediction for where the plastics industry is actually headed. Many pieces would have to fall together in just the right way for it to work. For one, Stegmann and his colleagues note in their paper, “a fully circular plastics sector will be impossible as long as plastic demand keeps growing.”

Plastics companies will happily meet that demand by ramping up production, says Steven Feit, senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, which did the emissions report showing what would happen if plastics manufacturing grew through the year 2050. “The pivot to petrochemicals has been the plan for years now for the broader fossil fuel industry,” he says. “It’s understood that plastics, as well as nitrogen fertilizers, are the two real pillars of petrochemicals, which are the engine of growth for fossil fuels.”

And as long as the plastics industry keeps producing exponentially more of it, there’s no incentive to keep the stuff in circulation. It’s just so cheap to manufacture, which is why recycling straight-up doesn’t work in its current form. (Among the many reasons why scientists are calling for negotiators of a new treaty to add a cap on production is that it would increase the price and demand for recycled plastic.) Another wrinkle is that plastic can only be recycled once or twice before it becomes too degraded. Some products, like multilayered pouches, have become increasingly complicated to recycle, so wealthy nations have been shipping them all to economically developing countries to deal with. Which is about as far from a circular economy as you can get.

Another issue is the space needed to grow the feedstock crops. “It increases the already huge pressure on land use,” says Jānis Brizga, an environmental economist at the University of Latvia, who studies bio-based plastics but wasn’t involved in the new paper. “Land use change has been one of the main drivers for biodiversity loss — we’re just pushing out all the other species.”

In 2020, Brizga published a paper calculating how much land it would take to grow enough plants for bioplastics to replace all the traditional plastics used in packaging. The answer: At a minimum, an area bigger than France, requiring 60 percent more water than the European Union’s annual freshwater withdrawal. (The new paper did model some land-use considerations, like restricting where biomass could be grown, but Stegmann says that a better understanding of the implications of this biomass growth is an avenue for future research.)

It would also take a whole lot of chemicals to keep those plants healthy. “Many of these crops are produced in intensive agricultural systems that use a lot of pesticides and herbicides and synthetic chemicals,” Brizga says. “Most of them are also very, very dependent on fossil fuels.”

And from a human health perspective, we don’t even want to keep plastics circulating around us. A growing body of evidence links their component chemicals to health problems: One study linked phthalates (a plasticizer chemical) to 100,000 early deaths each year in the U.S., and the researchers were being conservative with that estimate. Microplastics are showing up in people’s blood, breast milk, lungs, guts, and even newborns’ first feces, because we’re absolutely surrounded by plastic products — clothing, carpeting, couches, bottles, bags.

It’s also not clear what kind of climate effect the plastics will have after they’re produced. Early research on microplastics suggests that they release significant amounts of methane — an extremely potent greenhouse gas — as they break down in the environment. Even if a circular bioplastics economy attempts to keep carbon and methane locked up by turning plastics into long-term building materials or landfilling whatever can’t be used again, nobody knows for sure if it will work. We need more research on how plastics off-gas their carbon under different conditions.

The more plastic we produce, the more corrupted the environment grows — it’s already poisoning organisms and destabilizing ecosystems. “I fear that by the time we get enough answers to all of our questions, it will be too late,” says Kim Warner, senior scientist at the advocacy group Oceana, who wasn’t involved in the new paper. “The train will have already left the station, for what it’s doing to the atmosphere and the oceans and carbon and health and everything else.”

Matt Simon is a science journalist at Wired.

Apocalyptic highway fire exposes dangers of plastic tunnels

Automobiles on Friday burned in fire that broke out in a noise-barrier tunnel on the Second Gyeongin Expressway, which connects Incheon to Seongnam [YONHAP] An apocalyptic conflagration left a stretch of highway near Seoul a mess of molten plastic and melted cars. And it left relatives of the victims — the dead now numbering five — in utter disbelief. “It can’t be your dad,” a woman sobbed at a hospital with her daughters after hearing that her husband is one of the deceased. The fire broke out Thursday afternoon at the North Uiwang Interchange on the Second Gyeongin Expressway, also known as highway 110, which runs south of Seoul from Incheon toward the east and into the center of the country. According to investigators, a burning garbage truck ignited the plastic, translucent material of a noise-barrier tunnel that covered the elevated highway, and that 830-meter (2,723-foot) tunnel burst into flames, trapping cars and people in their cars. In addition to the five dead, 41 were injured and three remain in critical condition. The woman’s 66-year-old husband cannot be identified with certainty, and DNA testing will have to be done. The family was told the tests will be completed in a day or two. “Who should we blame?” she asked as she cried over her husband’s death. “Is this the fault of the truck driver?” The victim worked as a personal driver, a friend said. Before he was found dead, he called his boss and said he was inhaling smoke at the scene. “He really wanted to become a taxi driver,” the friend recalled. Cho Nam-seok, 59, who was at the accident site recalls hearing a loud thud after he barely escaped from his melting car. “A friend I was with in the car was not able to get out,” Cho said. His head is wrapped with bandages, and the back of his hand and left ear are severely burned. The plastic material that formed the wall of the tunnel is being blamed. According to officials, the tunnel was made of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), commonly known as acrylic. The noise-barrier tunnels in Korea are usually made out of PMMA, polycarbonate or glass, with PMMA being used most due to its low price. In terms of safety, it is the worst, according to experts. Compared to other materials, PMMA is easily ignited, melts quickly and tends to continue burning, according to a report from Korea Expressway Corporation in 2018. As the fire spread to the tunnel, the acrylic material melted and fell on the road and vehicles, which would have accelerated the fire. “As the public and the press have pointed out, the material of the noise-barrier tunnel seems to be the major issue of the accident,” said Minister of Land, Infrastructure and Land Won Hee-ryong after he visited the accident site on Friday morning. “Concerns on about PMMA material for being flammable have always been made by experts.” A total of 55 noise-barrier tunnels in Korea are to be fully inspected, while those still under construction will be finished with safer materials. Police started a full-scale investigation of the accident on Friday. The Gyeonggi Nambu Provincial Police Agency brought the garbage truck driver in for questioning on the possible charge of involuntary manslaughter. The driver reportedly said a fire broke out in his truck following the sound of an explosion. Authorities have blocked off 20 kilometers of the expressway. BY KIM JUNG-MIN, SON SUNG-BAE, KIM HONG-BUM, CHO JUNG-WOO [cho.jungwoo1@joongang.co.kr]

Amazon packages burn in India, last stop in broken plastic recycling system

Share this articleMuzaffarnagar, a city about 80 miles north of New Delhi, is famous in India for two things: colonial-era freedom fighters who helped drive out the British and the production of jaggery, a cane sugar product boiled into goo at some 1,500 small sugar mills in the area. Less likely to feature in tourism guides is Muzaffarnagar’s new status as the final destination for tons of supposedly recycled American plastic.On a November afternoon, mosquitoes swarmed above plastic trash piled 6 feet high off one of the city’s main roads. A few children picked through the mounds, looking for discarded toys while unmasked waste pickers sifted for metal cans or intact plastic bottles that could be sold. Although much of it was sodden or shredded, labels hinted at how far these items had traveled: Kirkland-brand almonds from Costco, Nestlé’s Purina-brand dog food containers, the wrapping for Trader Joe’s mangoes. Most ubiquitous of all were Amazon.com shipping envelopes thrown out by US and Canadian consumers some 7,000 miles away. An up-close look at the piles also turned up countless examples of the three arrows that form the recycling logo, while some plastic packages had messages such as “Recycle Me” written across them.Waste pickers in Muzaffarnagar sift through mounds of plastic trash for metal cans or or intact plastic bottles that could be sold, while children look for discarded toys. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergPlastic that enters the recycling system in North America isn’t supposed to end up in India, which has since 2019 banned almost all imports of plastic waste. So how did Muzaffarnagar become a dumping ground for foreign plastic? To answer that question, Bloomberg Green retraced a trail back from the industrial belt of northern India, through the brokers who ship refuse around the world, to the municipal waste companies in the US that look for takers of their lowest-value recycling. Finally, the search arrived at the point of origin: American consumers who thought — wrongly, as it turns out — that they were recycling their trash. It’s a system that’s supposed to cut pollution, spare landfills and give valuable materials a second life. But in Muzaffarnagar the failures are hard to miss. The region’s other major industry is paper production, with more than 30 mills dotted among the furnaces for making jaggery. Paper factories in India often rely on imported waste paper, which is cheaper than wood pulp. The nation’s paper makers need to import around 6 million tons annually to meet demand, and most of it comes from North America. This could be a recycling success story — were it not for all the plastic that comes mixed into all the waste paper. Exported paper recycling typically includes loose sheets from offices, old magazines and junk mail. But the bales are frequently contaminated with all kinds of plastic that consumers have tossed into their recycling bins, including the flimsy wrapping that holds water bottles together in a pack, soft food packaging and shipping envelopes. Most ubiquitous of all discarded plastics at the illegal dump sites were Amazon.com shipping envelopes thrown out by US and Canadian consumers some 7,000 miles away. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergDemand for paper has created an unaccountably large loophole in the ban on plastic waste from overseas. India may be bringing in as much as 500,000 tons of plastic waste hidden within paper shipments annually, according to a government environmental body that estimated the level of contamination at 5%. While the government allows up to 2% contamination in recycled paper, lax enforcement at ports means no one’s checking. So there’s no way to measure how contaminated the bales really are. Plastic contamination also comes through in recycled paper shipments sent from North America to other Asian countries, where dirty diapers, hazardous waste and batteries have all turned up. The amount of plastic trash coming into India in waste paper now is almost double the 264,000 metric tons that was legally imported in 2019 to the country before it imposed the ban in August of that year, according to figures from the United Nations Comtrade database. Since the ban, the government has allowed a small number of companies to import recyclable water bottles. Under the Basel Convention, a UN treaty that regulates international flows of hazardous waste, exporters of plastic are also required to obtain explicit consent from importing countries before shipments are sent.Perhaps one reason why the system is failing in India is that there are end users for plastic that mostly can’t be recycled. “There’s value in all plastics,” says Pankaj Aggarwal, the managing director of a local paper mill and chairman of the Paper Manufacturers Association for the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. “There are people who will buy it and have use for it.” Pankaj Aggarwal operates Bindlas Duplux Ltd., a paper mill that sends plastic that comes with imported waste paper to a cement plant for incineration Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergStill, Aggarwal says, he isn’t in the recycling business. That’s why he sends the unwanted plastic that comes through with the imported waste paper by tractor to a cement factory more than 400 miles away, where it ends up incinerated for energy. It’s a legal method of disposal in India. Other countries allow it too, though typically impose strict environmental standards. Cement kilns are hot enough to completely consume plastic, though the process is hardly climate positive. The greenhouse gas emissions from burning plastic are about the same as burning oil.Most of Muzaffarnagar’s paper mills have workers do a first-pass sift for the most valuable plastics such as water bottles, which can be recycled. The rest is carted off by unlicensed contractors who dump it at illegal sites throughout the city. There, it will be further sorted by laborers who are paid about $3 a day for potentially recyclable materials and dried out. The bulk is resold to paper and sugar mills to burn as fuel. The heat in boilers and furnaces at paper and sugar mills do not generate enough heat, however, so microplastic ash from the unconsumed remnant perpetually falls across the city. The mills also aren’t equipped with sufficient filtration to capture toxic emissions, equipment that can cost millions of dollars. In October alone, the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board fined nearly half of the mills in the city for burning plastic, improperly disposing of the waste and failing to manage the ash.“So much of the plastic waste from abroad has no saleable value, and it can’t be recycled,” says Ankit Singh, regional officer for the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board. “It’s just being dumped here and then will get burnt.”The long journey taken by most of the plastic that reaches Muzaffarnagar is difficult to trace, even when branding indicates a North American origin. But every so often an identifying mark provides a clear starting location. One plastic envelope with a United States Postal Service label stood out from the piles at a local dump site because it still had a name and address printed directly on it. The parcel had been shipped to Laurie Smyla, a 73-year-old retiree from Sloatsburg, New York. There was no doubt in her mind: Smyla had put that envelope into her recycling bin. “That’s polyethelene, and I’d recycle that. If it’s got the recycling symbol on it, into the bin it goes,” she says. “I get a lot of Amazon packages, and they all go into the bin, too.” Smyla has a degree in environmental science and even served as coordinator for the local recycling program in the late 1980s, as she explains when reached by phone. She was able to quickly identify the envelope as polyethylene, the most common type of plastic. It arrived in September with prescription medication. Most consumers like Smyla have been lulled into thinking that the three-chasing arrows, a marketing symbol created by the petrochemical industry, found on many packages means it’s recyclable. In fact, it simply indicates which type of plastic it is. She was dismayed to learn that the plastic packaging she put into her recycling bin had traveled thousands of miles to pollute someone else’s backyard. “That is really a shame, considering that that stuff is not biodegradable and is going to last a millennium,” Smyla says. “I feel sorry for anyone who lives within a 5-mile radius of the site you’re standing on.”That would include Bobinder Kumar, a 35-year-old mechanic who lives with his wife and three kids in a bare two-room home. The plastic dump that had the envelope addressed to Smyla is just a few hundred feet from his home. Nearly every inch of the 3-acre site is strewn with trash. “We can’t escape the smell of the trash, even in our home,” he says. “It’s very terrible to live close to the site, but what can we do?”A paper mill’s smokestack in Muzaffarnagar spews black smoke, which experts say is the result of incomplete combustion that often leaves particles in the air. The area’s pollution control agency says black smoke is one indication that plastic may be burning. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergAnti-smog guns spray water on busy roads in Muzaffarnagar to settle pollution particles from the air. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergBy far the most common logo in the heaps just outside the Kumar home is the curved line and arrow of Amazon.com Inc. The blue-and-white plastic shipping envelopes favored for small parcels by the online retail giant were easy to spot on visits to six illegal dump sites in Muzaffarnagar. The logo was evident in piles of plastic waiting to be burned at several sugar mills. The charred, half-melted remains of an Amazon envelope could be picked out from fly ash at a dump used by a local paper mill.Amazon wouldn’t comment on the presence of its packaging in Muzaffarnagar. The company “is committed to minimizing waste and helping our customers recycle their packaging,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “Since 2015, we have invested in materials, processes, and technologies that have reduced per-shipment packaging weight by 38% and eliminated over 1.5 million tons of packaging material.”Amazon generated 709 million pounds of plastic packaging waste in 2021 from all sales through Amazon’s e-commerce platforms globally, according to a report by international environmental group Oceana, up 18% from the prior year. At that volume the company’s air pillows to protect packages alone could circle the Earth more than 800 times. In a December blog post, Amazon said it reduced average plastic packaging weight per shipment by over 7% in 2021, resulting in 97,222 metric tons of single-use plastic being used across Amazon-owned and operated global fulfillment centers to ship orders to customers.Amazon delivery packages tout the company’s commitment to sustainability. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergAmazon’s bubble-lined plastic bags carry the recycling logo that’s often criticized for confusing consumers into thinking its packaging is easily recycled. Soft plastics used in bags and wrappers are some of the hardest and least economically viable materials to recycle. Most American recyclers can’t process them.Closer inspection of Amazon’s envelopes shows “Store Drop-off” printed with a link to How2Recycle, a third-party organization that offers educational material on recycling. Users who want a list of drop-off locations are directed to another website for locations that accept plastic items with the Store Drop-off logo, including big-box retailers such as Safeway, Target and Kohl’s. Amazon said it doesn’t control the management of plastics waste once it’s dropped-off by customers.By the time plastic parcels arrive in India, though, there’s no question of reusing the material for anything other than fuel. Jaggery is a cane sugar product boiled into goo at some 1,500 small sugar mills in the area. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergIt’s been routine practice for Mohammad Shahzad, a sugar mill owner in Muzaffarnagar, to burn bagasse — dry sugarcane pulp — mixed with plastic scrap to fuel his furnace. Next to Shahzad’s furnace sits a large pile of bagasse mixed in with bits of plastic packaging to go into the fire, including an Amazon package envelope, Capri Sun drink pouch and the outer layer of plastic that held together a 12-pack of bottles of Kirkland-brand juice drinks.The remnants of sugarcane aren’t quite combustible enough for the process, and wood is expensive. Mixing in plastic economizes the operation. “Plastic heats up the sugar well,” says Shazad, whose crew of six works while a group of children run about. “We make very little money.” He says other sugar mill owners use the same approach. Shahzad’s mill sits off a stretch of road lined with sugarcane fields and operations that are practically open-air except for a thatched roof. Such mills are rudimentary: sugarcane is fed by hand into a machine that squeezes juice from it, leaving behind pulpy remnants that will be dried and later on burned as fuel to boil the juice down to what will become raw sugar when cooled. Sugar mills in Muzaffarnagar burn bagasse — dry sugarcane pulp mixed with plastic scrap — to fuel their furnaces. The remnants of sugarcane aren’t quite combustible enough alone for the process, and wood is expensive. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergIn the villages around the sugar and paper mills, residents say they usually know when plastic has been burnt overnight because they wake up to a layer of ash that coats terraces, crops and anything left outdoors. Burning plastic releases a slew of toxins into the air, including dioxins, furans, mercury and other emissions that threaten the health of people, animals and vegetation, according to multiple studies. Exposure to burning plastic can disrupt neurodevelopment as well endocrine and reproductive functions, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in the US. Other chemicals emitted in burns, including benzopyrene and polyaromatic hydrocarbons, have been linked to cancer.The burns, along with other industrial pollution, leave a thick gray-yellow smog over Muzaffarnagar that rarely lifts. On most days the air-quality index in the city is above 175 — or “unhealthy” — and there are often warnings to limit exposure outside. Around Muzaffarnagar, respiratory problems such as asthma and bronchitis along with eye infections associated with air pollution and the burning of plastic are on the rise, up as much as 30% over the last few years, according to Muzaffarnagar’s chief medical officer. District officials have started visiting factories overnight to identify culprits and fine them. But it isn’t enough to clear the air. In the villages around the sugar and paper mills, residents say they usually know when plastic has been burnt overnight because they wake up to a layer of ash that coats terraces, crops and anything left outdoors. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergParmanand Jha makes surprise inspections of paper mills suspected of burning plastic and shuts them down on the spot. The subdivisional magistrate in charge of Muzaffarnagar city has disconnected conveyor belts and chutes that sent plastic into the boilers at several paper mills this year. He knows his interventions are not a real deterrent. “They can save money burning plastic,” he says, “even with the fines.”The furnace operators of Muzaffarnagar have found a way to profit from a waste stream that municipal collectors thousands of miles away see as valueless. The broken pathway that takes would-be recycled plastic from a town in New York to the furnaces of India first passes through a county recycling program that — understandably — doesn’t want to deal with plastic envelopes and packaging trash. District official Parmanand Jha has caught paper mills burning plastic in the middle of the night and shut them down. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergThe sorting center that took in Smyla’s envelope and other discarded materials for recycling from the homes in Sloatsburg doesn’t take soft plastics because it wraps around the sorting machines and snarls them up. Soft plastics “constitute contamination because of what it does to the equipment,” says Gerard M. Damiani Jr., executive director for Rockland County Solid Waste Management Authority, which handles waste for 332,000 residents, including Smyla. “They’re not acceptable items in our program.” Most recycling centers in the US won’t accept soft plastic.Damiani says consumer packaging and bags are the responsibility of retailers who sell the products. Under New York state law, retailers are required to offer store drop-off points for consumers to bring back and recycle soft plastics and shopping bags. He says the county isn’t responsible for handling the retailers’ recycling bins, and he has no idea what happens to those items once they’re dropped off.Just because most consumer packaging waste isn’t eligible doesn’t mean that it stays out of the system. It’s possible Smyla’s envelope got mixed up with a paper load collected by the county, which has a contract with a New Jersey-based company called Interstate Waste Services to handle recycling. It’s also likely the plastic pouch was sorted at the recycling facility and accidentally sent into the paper stream. According to Damiani, the Interstate representative who handles Rockland’s waste told him it does export some paper recycling overseas.Interstate’s facility in Airmont, New York, recycles commingled paper of all grades from Rockland County and lists N&V International and N&V Syracuse as the destination for most of its recycled paper waste in 2020, according to an annual report filed to New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation. It was not possible to confirm the chain of custody for Smyla’s shipping envelope, and N&V didn’t respond to requests for comment.Rockland’s contract with Interstate doesn’t preclude sending materials overseas, but Damiani is against it. “You should deal with your own waste within your own borders,” he says. Bloomberg Green contacted several Interstate executives to ask how plastic waste from suburban New York could have ended up dumped in a field in India. None responded. Officials have started visiting factories overnight to identify culprits and fine them. But it isn’t enough to clear the air. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg The movement of waste from rich countries to poorer ones with laxer enforcement tends to be facilitated by brokers, who either charge a fee to dispose of unwanted material or buy it cheaply and sell it overseas. The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime has called brokers “key offenders” in the black-market waste trade, with links to major fraud and criminal gangs.The trade in residential waste paper is volatile, with aggregate prices for mixed paper dropping to zero in the last two months, compared to $80 a ton this time last year. Most brokers are giving it away, with importers paying just the shipping cost, says Bill Moore, president and owner of Moore & Associates, a paper industry consultant in Atlanta. That translates into meager incentives for recycling centers and brokers to make sure that plastic contamination in bales of recycled paper is low and meets India’s little-enforced legal threshold. At many older facilities in the US, residential recyclables that get mixed together at collection are sorted into glass, metal and plastic. Paper, magazines and mailers are weeded out for recycling. But flat plastic packaging and shipping envelopes can easily pass as paper.“Shipping envelopes and thinner plastic materials act like paper, and it floats into the paper stream,” says Moore. “It’s exactly the type of plastic that will be contamination in a paper bale and get shipped to India.”Residue ash containing semi-burnt plastic bags from a steam boiler of a paper mill arrives at a scrap yard in Muzaffarnagar. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/BloombergSmyla felt manipulated to find her carefully sorted waste had joined the mountains of trash at Muzaffarnagar. “I feel betrayed as a consumer,” she says. “That recycling symbol — it’s all a marketing feel-good message and very deceptive. It should not be harming other people in other parts of the world.”For Kumar, the mechanic living beside heaps of North American plastic waiting to burn, those good intentions can’t blunt the harm that’s an everyday fact of his life. “My kids and the neighbors all have allergies and breathing problems,” he says. “I worry about diseases.”—With assistance from Leslie Kaufman and Manoj KumarThe visual media in this project was produced in partnership with Outrider Foundation.More On Bloomberg

Countries resolve to protect cetaceans from marine plastic pollution

Following the adoption of a Resolution on Marine Plastic Pollution at the 68th International Whaling Commission conference (IWC68) in October, member countries will have to report on the status, reduction, recycling, and reuse efforts on marine plastic pollution.At IWC68, member nations adopted a resolution to support international negotiations on a treaty to tackle plastic pollution. The body also recognised the transboundary nature of marine plastic pollution and the importance of international cooperation.The Resolution on Marine Plastic Pollution commended the UN Environment Assembly’s March 2022 decision to begin negotiations on an international legally binding instrument to tackle plastic pollution, including in the marine environment.For India, local communities will be crucial stakeholders in tackling ocean plastic, say biologists. At the 68th International Whaling Commission conference (IWC68) in Slovenia in October, member nations adopted a resolution to support international negotiations on a treaty to tackle plastic pollution. Countries will now aim to report on the status of marine plastic debris. For India, local communities will be crucial stakeholders in tackling ocean plastic.

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) is an inter-governmental body responsible for the management of whaling and the conservation of whales.

It has a current membership of 88 governments from all over the world, including India, which played a critical role in amending the text of the resolution to incorporate reporting commitments on the status of marine plastic by member countries.

Confirming that the impacts of marine plastic pollution on cetaceans is a “priority concern” for the IWC, the Resolution on Marine Plastic Pollution adopted at IWC68, commended the UN Environment Assembly’s March 2022 decision to begin negotiations on an international legally binding instrument to tackle plastic pollution, including in the marine environment.

Though the IWC’s main focus is to keep a check on whale stocks and ensure there is a balance in the whaling industry, it is also concerned with plastics and marine debris because they impact the survival of whales, dolphins, and porpoises, among other marine species.

Plastic ingestion and entanglement in nets are the other issues that lead to injury and death of such marine animals. Welcoming the IWC68 resolution, Sajan John, a marine biologist at Wildlife Trust of India, says, “Since whales and whale sharks are filter feeder animals, they clean the water. When they ingest plastic, it could get into their digestive system and create many issues.”

The International Whaling Commission conference (IWC68) was held in Slovenia in October 2022. Photo by Sharada Balasubramanian/Mongabay.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that almost 13 million tonnes of plastic enter the oceans yearly, affecting approximately 68% of cetacean species. Plastic ingestion cases are found in at least 57 out of the 90 known cetacean species (63.3%). Ingestion of plastic has been recorded in all marine turtle species and nearly half of all surveyed seabird and marine mammal species. Apart from this, those species that are not directly impacted by ingestion or entanglement could suffer from secondary impacts such as malnutrition, restricted mobility and reduced reproduction or growth, experts at the conference shared.

This resolution, with amendments from India, was one of the major successes at the IWC meeting. The draft Resolution on Marine Plastic Pollution was proposed by the Czech Republic on behalf of the European Union member states parties to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling; the resolution was co-sponsored by the United States of America, the United Kingdom, the Republic of Korea, Republic of Panama and India.

Following the adoption of the resolution, India, at the IWC68, shared that in 2019, “20.34 million tonnes of plastic was generated in India, and 60% of the same were recycled against the world average of 20%. So the solid waste management capacity in India, which was only 18% in 2014, increased to 70% in 2021. The Bureau of Indian standards classifies microbeads in cosmetics as unsafe and has banned microbeads in cosmetics. This was implemented in 2020 along with the ban on importing plastic waste.”

At the discussion on the resolution of the IWC meeting, Bivash Ranjan, Additional Director General of Forests at India’s Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC), who was with the country delegation at the meeting, said that one of the early threats India perceived for the marine aqua fauna was plastics.

Ranjan said, “Apart from banning single-use plastic and microbeads, India has also taken steps to clean the coasts and make them plastic-free.” He said that this move (removing all the plastic litter across coasts) will further strengthen the conservation plan of the dolphins.”

Actions post-resolution

In the follow-up to the IWC resolution, the next step is for countries to report on marine plastic waste.

India made an amendment to the resolution asking member countries to report on the status of marine debris around their country and the amount of plastic recycling and usage.

On the implications of the IWC68 resolution to the conservation of cetaceans and whales, Vishnupriya Kolipakkam, Scientist, Wildlife Institute of India (WII) said, “This will help us to identify where and what the problem is. Otherwise, it’s just a resolution that says, let us reduce the use of plastic. The member countries will take the route of sustainable use and reduce single-use plastic. It has a broad general resolution, and many countries are already doing this. But because of India’s intervention, we suggested that member countries have to report back on the status and recycling usage of plastic. Now, it would be more relevant because we can call on people and governments who are not actively doing anything,” she said.

Challenges and solutions for implementation

However, the success of implementing the IWC68 resolution will depend on many factors. In India, a tropical country, plastic pollution does not emerge from a single point source, points John. Many tributaries of rivers drain into the ocean. Many human activities are localised in the rivers’ upstream, and plastics dumped into the rivers eventually end up in the oceans.

John told Mongabay-India, “Most of the time when we talk about marine plastic pollution, it is about removal from the coastal beach and clean up activities. Everything is centered around the coastal area. We are trying to address the issue on the periphery, but we are not trying to address the issues from the upstream. Not much occurs upstream, and there is little awareness or action.”

He pointed out that complete tracking of plastic and collecting the data is beyond quantifiable. “One, we are on the tropical side of the oceans; two, we depend heavily on disposable plastic, so quantifying that would be challenging,” John added.

Disposable plastic has contributed to the marine debris in the ocean, which affects the marine organisms. Photo by Hajj0 ms/Wikimedia Commons.

Local communities will be crucial to the IWC68 resolution’s implementation.

At WTI, John has been looking at different approaches to tackling India’s marine plastic pollution problem. He works with the fisher community, telling them to bring back marine debris found in the ocean. Involving local fishing communities that go to the sea daily is one way to remove plastics from the ocean effectively.

“India has a coastline spanning 8,000 kilometres, and fisher families have almost tripled. If we mobilise them on the east coast, west coast, and the two of our island territories, we can recover plastic,” said John.

The major issues in Indian coasts are bottles, polythene bags, plastic wrappers, and covers. The nets contribute to a small part of the debris, he added.

Also, a complete ban on plastic will be tough. John says, “We have moved from biodegradable to plastics, so everything revolves around plastic now. Plastic use is high in the medical industry, especially during the pandemic. Polymer science has also advanced. If there is an alternative to single-use plastic, those could be given at a subsidised rate. But if the price of the alternative product is high, then people would opt for the cheaper plastic.”

IWC’s initiative on marine plastics

Almost two decades ago, the IWC recognised the significance of marine debris impacts on cetaceans. Plastic pollution spans five of the eight priority areas of environmental concern identified by the IWC’s scientific committee. This was endorsed by the commission in IWC Resolution 1997. In addition, Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG 14) aims to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources, including preventing and reducing marine pollution of all kinds by 2025.

Within the framework of IWC, there was another crucial resolution in 2018 on ghost gear entanglement in cetaceans. The Commission has encouraged the conservation committee, scientific committee, and whale killing methods and welfare issues working group to consider engaging organisations on marking the gears used for fishing so that the net entanglement issues could be examined.

Marine debris like ghost nets continue to pose a threat to marine wildlife. Photo by Tim Sheerman/Wikimedia Commons.

In the IWC68 resolution, the body also recognised the transboundary nature of marine plastic pollution and the importance of international cooperation by IWC’s contracting governments and other international organisations, including the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Arctic Council and International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

As a result, the IWC secretariat was directed to look at ways in which they can engage as a stakeholder within the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) process.

It was recommended that the contracting countries submit reports, voluntarily, to the scientific progress committees on the status, reduction and recycling of plastic, and ingestion in stranded marine animals. The Commission, in the recent resolution, also recommended the IWC secretariat to add marine debris mapping along the Important Marine Mammal Areas (IMMAs). Further, there were also requests to reduce single-use plastics in the IWC day-to-day operations itself. All this will be discussed further in the next meeting, IWC 69.

[This story was produced with support from the Earth Journalism Network’s Biodiversity Media Initiative]

Read more: Unpacking the presence of microplastics in the Bay of Bengal

Banner Image: A humpback whale. Photo by Christopher Michel/Wikimedia Commons.