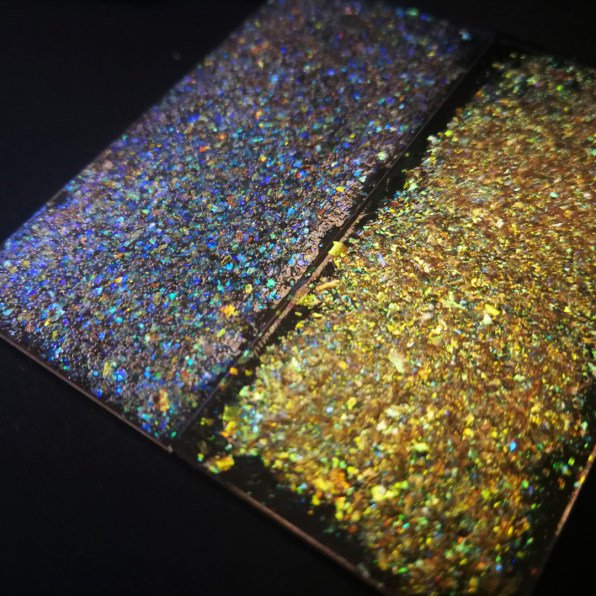

Almost all of the glitter you’ve ever used is still floating around the planet. This new formulation has just one ingredient, but it’s still as shimmery as the original.

[Photo: courtesy University of Cambridge]

By

Category Archives: Plastic Pollution Articles & News

Despite deals, plans and bans, the Mediterranean is awash in plastic

The Mediterranean is considered to be one of the world’s most polluted bodies of water due to waste disposal problems in many countries bordering the sea, as well as the intensity of marine activity in the region.There are several existing policies and treaties in place aimed at regulating plastics and reducing plastic pollution in the Mediterranean, but experts say more international cooperation is needed to tackle the problem.Citizen science organization OceanEye has been collecting water samples to measure the amount of microplastics present in the surface waters of the Mediterranean. MARSEILLE, France — Pascal Hagmann lowered a manta trawl — a ray-shaped, metal device with a wide mouth and a fine-meshed net — off the side of his sailboat and into the blue waters off the coast of Marseille, France. Then he motored around at 3 knots. The manta trawl skimmed along the surface, taking in gulps of seawater and catching whatever was floating inside it.

“Maybe there will be [plastic], maybe not, you never know,” Hagmann, founder and CEO of the Swiss citizen science NGO OceanEye, told me in September as he steered his 40-foot (12-meter) sailboat, Daisy. “It depends on the surface currents and also on the weather forecast.”

Pascal Hagmann, founder and CEO of the Swiss citizen science NGO OceanEye, deploying a manta trawl off the coast of Marseille, France. Image by Elizabeth Claire Alberts for Mongabay.

After 30 minutes, Hagmann and Laurianne Trimoulla, OceanEye’s communication manager, tugged the manta trawl back on board. They took it apart and inspected the net.

“This blue here definitely is one,” said Trimoulla, pointing with the end of a screwdriver at a small piece of plastic. “And then there is a film — packaging wrap.”

Back at harbor, Hagmann went below deck to look at the sample under a microscope. He gestured to the eyepiece. “Have a look,” he said.

I squinted through the lens. There was a collage of plankton, blue threads of plastic fishing line, and white and green plastic particles. Some of these were nurdles, raw plastic pellets used as feedstock to manufacture an array of plastic products, from drink bottles to plastic bags to car parts.

“This is the point that I think is really frightening,” Hagmann said. “This pollution is just everywhere.”

The Mediterranean is considered to be one of the most polluted bodies of water in the world, with hundreds of tons of plastic blowing into the sea, mainly from land, every single year. One study published in 2015 in PLOS ONE put the amount of plastic pollution in the surface waters of the Mediterranean on par with what’s found in the accumulation zones of the five subtropical ocean gyres, including a collection of debris in the North Pacific gyre that’s known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

A number of governments and intergovernmental organizations are trying to address this issue with policies and treaties that would hold companies and nations responsible for the plastic they use, transport and discard. But as of yet, none of these efforts seem to be stemming the tide of plastic steadily pouring into the Mediterranean.

A manta trawl deployed off the side of OceanEye’s sailboat, Daisy, in September 2021. Image by Elizabeth Claire Alberts for Mongabay.

‘Plastic trap’

About 20% of the plastic swirling around the Mediterranean comes from the vessels that crisscross the sea year-round, as well as from fishing and aquaculture activities, according to a 2018 WWF report. The other 80% comes from the land, the report says. Mercedes Muñoz, who manages activities related to plastic pollution at the IUCN, a global conservation authority, said the land-based plastic pollution is largely due to inconsistent waste management schemes.

“The collection of municipal solid waste is still a significant issue in most south Mediterranean countries,” Muñoz told Mongabay in an interview via phone and email. “Only a few countries have reached full waste collection coverage.”

For instance, one study found that Lebanon, which has 225 kilometers (140 miles) of Mediterranean coastline, only properly disposes of 48% of its waste. The rest is dumped outside landfills or burned, and as a result, much ends up in the sea. A 2018 NPR report even found that developers in Lebanon have been deliberately dumping thousands of tons of trash into the sea as a way to reclaim land from the ocean.

Turkey is known to be the biggest contributor to plastic pollution in the Mediterranean, allowing about 144 metric tons to enter the sea every day, according to the WWF report.

Trash piled on a beach in Algeria. Image by Belgueblimohammed2013 / Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Once plastic has entered the Mediterranean Sea, it tends to stay there because of the sea’s semi-enclosed shape and the currents that only move water out via a deep-water layers. It’s a “plastic trap,” as the WWF report puts it.

Plastic will also change shape, breaking into smaller and smaller pieces. Any fragment smaller than 5 millimeters, about three-sixteenths of an inch, is considered a microplastic. Some of these microplastics will remain in the surface waters, while others will drift through the water column, travel with the currents and settle on the seafloor.

“The concentration [of plastic pollution] in the Med is pretty bad,” Lucile Courtial, executive director of Monaco-based NGO Beyond Plastic Med, told Mongabay in a phone interview. “If we don’t act on it, it will [become] much worse.”

A 2020 report released by the IUCN, to which OceanEye contributed data, suggests that the Mediterranean has already accumulated nearly 1.2 million metric tons of plastic. A recent United Nations report says that 730 metric tons of plastic waste end up in the Mediterranean Sea every single day, and that plastic could outweigh fish stocks in the near future. However, some experts say there is an ongoing need for more data to understand if plastic pollution in the Mediterranean is increasing or decreasing.

The WWF report also suggests that plastic pollution is costing the EU fishing fleet about 61.7 million euros ($70.7 million) every year because of a “reduction in fish catch, damage to vessels or reduced seafood demand due to concern about fish quality.”

Trash piled on a beach in Rhodes, Greece. Image by Pxfuel (CC0 license).

‘Gaps in the whole chain’

One of the most rigorous agreements in place to address the global issue of plastic pollution is the Basel Convention, the U.N. treaty formulated in 1989 to regulate the international shipment of hazardous waste. In 2019, an amendment to the Basel Convention added plastic to the other kinds of waste the convention regulates, with changes scheduled to take effect in 2021.

Rolph Payet, executive secretary of the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm conventions, said the amendment allows countries to holds companies accountable for any plastic they transport or trade through the enactment of national laws and norms.

“We identify gaps in the whole chain because some people are saying, ‘Yes, we are disposing, we are doing very well,’” Payet told Mongabay in September at the IUCN Congress in Marseille. “But then we find the bottles in the ocean, right? So this will help to narrow down where the problems are and help … companies be more accountable in terms of their waste.”

However, a major gap in the effectiveness of the Basel Convention is the fact that the United States has not yet joined the Basel Convention, despite being a major exporter of hazardous waste, including plastic, worldwide. Right now, the U.S. is the only major nation that has not implemented the Basel Convention.

Payet said that the U.N. plans to use OceanEye’s data, as well as other global data sets, to help establish a baseline for the amount of plastic in the Mediterranean that can be used in the future to determine if the Basel Convention is having a positive impact on the regulation of plastic. However, he added that it may take a few years before these effects can be seen since countries are still working to implement the new rules.

Another policy aiming to address the issue of plastic pollution in the Mediterranean is the Regional Plan on Marine Litter Management (RPML), which was adopted by contracting parties to the Barcelona Convention, including the European Union, in 2013. In short, the plan legally requires parties to “prevent and reduce marine litter and plastic pollution in the Mediterranean” and to remove as much existing marine litter as possible.

Microplastics mixed with organic matter in the net of a manta trawl. Image by OceanEye.

Then there’s the European Union’s recent ban on many kinds of single-use plastics, including cotton bud sticks, cutlery and beverage stirrers, as part of the EU’s transition to a “circular economy.” When EU member states cannot ban these items, they need to implement an “ambitious and sustained reduction,” according to the directive.

But are countries abiding by these policies and enforcing them? Courtial said these are tricky questions to answer.

“In general, we need regulations and guidelines and these kinds of treaties so that countries actually try to [achieve] the goals that are there,” she said. “The main problem … is that there is no real way of enforcing the countries to actually respect it, and implement the different actions or activities.”

Courtial added that it’s difficult to coordinate an effort between the 22 countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, especially as the countries are in different stages of economic development.

“Some of the countries have more problems trying to feed their people, so dealing with plastic waste is really not a priority,” she said. “That’s what makes it really difficult.”

Experts are placing a lot of hope in a possible U.N. treaty that would legally require parties to address the entire life cycle of plastics, from production to disposal.

Muñoz says this treaty would be a “great step forward and very needed” since there needs to be more international cooperation on the issue.

“We always say that the Earth is just one big ocean,” she said. “What happens on one side will probably have some impact on another part. So we need international commitments that are aligned and they’re working together to reduce the problem.”

But the U.N. treaty has yet to come to fruition — and it is also not clear how effective it would be at stopping plastic from spilling into the Mediterranean.

Hagmann looking at a microplastic sample through a microscope. Image by Elizabeth Claire Alberts for Mongabay.

‘That’s why we carry on’

While research shows that the Mediterranean holds a considerable amount of plastic, some experts say more data is needed to fully understand the complexities of the issue. For instance, Hagmann said there’s still not enough data to understand how plastic pollution is dispersed across the Mediterranean and how the levels of pollution might change over time.

The need for this data is what motivated Hagmann to repurpose his recreational sailboat to become a citizen science vessel 10 years ago, and start cruising through the Mediterranean with a manta trawl to collect samples from the water’s surface. He also recruited a network of volunteers operating 10 other vessels to gather additional plastic pollution data, not only in the Mediterranean, but also in the Arctic and Atlantic.

Hagmann, who has an engineering background, says OceanEye’s mission is to contribute data to intergovernmental organizations that are monitoring plastic pollution and actively working on solutions. Already, OceanEye’s data have been used by the European Commission, United Nations and the IUCN in their databases and reports.

Hagmann and his volunteers focus on surface trawls, using the sampling protocol formulated by environmental scientist Marcus Eriksen, co-founder of the California-based plastic pollution research institute 5 Gyres.

Microplastic samples ready to be processed at OceanEye’s lab in Geneva. Image by OceanEye.

In June and July, Hagmann and a small crew sailed Daisy around the Adriatic Sea, taking some data samples near coastlines and others in open water, depending on weather conditions and cargo routes. Then, in September, immediately following the IUCN Congress in Marseille, the OceanEye crew sailed through the central Mediterranean to collect additional samples. So far, only the samples from the Adriatic expedition have been processed at OceanEye’s lab in Geneva.

Hagmann said the processed samples contain “particularly high concentrations of plastic” of more than a million particles weighing 1,000 grams per square kilometer, or about 91 ounces per square mile. But the final results, he said, still need further interpretation and analysis by outside experts.

“We provide the data … and then it’s [out of] our hands,” said Trimoulla of OceanEye. But she said she’s optimistic that the organization’s work will have a positive effect, arguing that the more data they provide to various bodies, the bigger the impact these bodies can muster.

“That’s why we carry on,” she said. “We have to.”

Citations:

Alessi, E., & Di Carlo, G. (2018). Out of the plastic trap: saving the Mediterranean from plastic pollution. Retrieved from WWF Mediterranean Marine Initiative website: http://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/a4_plastics_med_web_08june_new.pdf

Boucher, J., & Billard, G. (2020). The Mediterranean: Mare plasticum. Retrieved from IUCN website: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2020-030-En.pdf

Cózar, A., Sanz-Martín, M., Martí, E., González-Gordillo, J. I., Ubeda, B., Gálvez, J. Á., … Duarte, C. M. (2015). Plastic accumulation in the Mediterranean Sea. PLOS ONE, 10(4), e0121762. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121762

Mediterranean Action Plan and Plan Bleu. (2020). Retrieved from United Nations Environment Programme website: https://planbleu.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SoED_full-report.pdf

Banner image caption: Trash-filled plastic bags in the ocean. Image by SMR / Pixahive (CC0 License)

Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a staff writer for Mongabay. Follow her on Twitter @ECAlberts.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Citizen Science, Conservation, Environment, Environmental Policy, Marine, Marine Biodiversity, Marine Conservation, Marine Crisis, Marine Ecosystems, Microplastics, Ocean Crisis, Oceans, Plastic, Pollution, Science, Waste, Water Pollution

PRINT

COP26: Plastic pollution trackers released off Scotland

Credit: OneOcean

On the penultimate day of COP26, scientists have deployed plastic pollution tracking devices into the ocean around Scotland.

Report casts doubts on petrochemical growth in Appalachia

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — A report released Wednesday by the Ohio River Valley Institute says that changing market forces are likely to impede the growth of the petrochemicals industry across Appalachia.

The report, “Poor Economics for Virgin Plastics: Petrochemicals Will Not Provide Sustainable Business Opportunities in Appalachia,” points to several factors that will hamper the expansion and development of new petrochemical complexes across the region.

Among these are environmental concerns from consumers and investors over pollution caused by petrochemicals such as polyethylene – the core feedstock produced by ethane “cracker” plants.

The future of food shopping might be plastic-free

Two years ago, efforts to kick the country’s plastic addiction were on fire. Municipalities around the country were implementing plastic bag taxes, while mainstream shoppers embraced reusable grocery bags and flocked to the bulk aisles for foods like beans and nuts.However, all that came to a halt when stopping the spread of COVID-19 became the country’s top priority. Almost overnight, grocery stores closed their bulk-shopping sections, coffee shops stopped filling reusable coffee mugs, and individually wrapped everything took center stage.Now, signs are emerging that the fight against plastic is getting back on track. One of the most notable of those signs came from Kroger last month, when the nation’s largest grocery chain announced it was expanding an online trial with Loop, an online platform for refillable packaging, to 25 Fred Meyer store locations in Portland, Oregon.While consumer reuse models “got punched in the face” by the pandemic, Loop’s Tom Szaky said the demand is still there, and mainstream grocery stores are going to need to find a way to meet it.Kroger plans to offer a separate Loop aisle in these stores. The products, which will include a mix of items in food and other categories, can be bought in glass containers or aluminum boxes. When they’re empty, customers return the containers to the store to be cleaned and used again. Originally scheduled for this fall, the launch has been postponed to early 2022 because of supply chain challenges, but a spokesperson said they will continue to work with their brand partners to consider items that can be added to expand the program over time.The partnership is a heartening sign after a tough year, said Tom Szaky, CEO and founder of TerraCycle, the company behind the Loop initiative. “Overall, I was very worried that the pandemic would shift the conversation away from waste,” Szaky told Civil Eats. “It didn’t slow down. In fact, the environmental movement’s only gotten stronger.” While consumer reuse models—reusable grocery bags, refillable coffee mugs—“got punched in the face,” he said, it was mainly because retailers stopped allowing them for safety reasons.And while Loop’s growth was slowed by the pandemic, it was for the same factors that upended many companies’ plans—not because interest was drying out, said Szaky. The demand is still there, he adds, and he’s bullish on the idea that mainstream grocery stores are going to need to find a way to meet it.The Kroger–Loop partnership could be the first true test of this theory. It’s the latest in a steady string of new partnerships for Loop, but until now all of the company’s U.S. packaging partners have been in other categories, such as cosmetics and cleaning products. Loop does work with a number of food companies outside the country, including Woolworths in New Zealand, Tesco in the U.K., Aeon in Japan, and Carrefour in France. Szaky says they’re also working with a grocery store in France to bring reusable packaging to fish and meat. Loop, which also works with Walgreens in the U.S. and fast food chains McDonald’s, Burger King, and Canada-based Tim Hortons, expects nearly 200 stores and restaurants worldwide to be selling products in reusable packages by the first quarter of 2022, according to the Associated Press, up from a dozen stores in Paris at the end of last year. Some experts in the space are convinced that more will follow.“It’s just a matter of time before other companies come on board,” says Colleen Henn, founder of All Good Goods, a plastic-free pantry subscription business based in San Clemente, California that sells food in reusable glass jars and paper bags. “Once somebody does it, people start to see, ‘Oh, avoiding single-use plastic is] not that complicated.’ Because it’s really not.”She would know. Henn didn’t spend the last year adapting her business; she first launched her seemingly improbable business model during—and really because of—the pandemic. She had grown frustrated that the country’s waste-reduction initiatives were falling by the wayside. “I went online and tried to find a store that shipped food to your door without plastic, and I couldn’t find it. So I created it,” said Henn.All Good Goods specializes in pantry goods like beans and pasta, nuts and dried fruit, and growth has been strong and steady since the launch. She increasingly fields phone calls from other stores looking for advice on how to avoid plastic in their operations, and as she engages with more companies, she’s optimistic that she will have a trickle-up effect within the industry. “I reach out to brands [we’re considering carrying] and see what their wholesale options are; if they’re not paper-based, if they’re not backyard-biodegradable, we move on,” said Henn.

26,000 tons of plastic waste, PPE from COVID pandemic pollute ocean

Some 8 million metric tons of pandemic-related plastic waste have been created by 193 countries, about 26,000 tons of which are now in the world’s oceans, where they threaten to disrupt marine life and further pollute beaches, a recent study found.The findings, by a group of researchers based in China and the United States, were published this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal. Concerns had been raised since the start of the coronavirus pandemic that there would be a boom in plastic pollution amid heightened use of personal protective equipment and rapid growth in online commerce. The study is among the first to quantify the scale of plastic waste linked to the health crisis.The cost of the increase in plastic waste has been keenly felt by wildlife. As of July, there were 61 recorded instances of animals being killed or disrupted by pandemic-linked plastic waste, according to a Dutch scientist-founded tracking project. Among the widely publicized examples are an American robin that was found wrapped up in a face mask in Canada and the body of a perch wrapped in the thumb of a disposable medical glove that was found by Dutch volunteers; National Geographic called the latter the first documented instance of a fish being killed by a glove.Although only about 30 percent of all covid cases were detected in Asia as of late August, the region was responsible for 72 percent of global plastic discharge, the study found. The researchers said this was due to higher use of disposable protective equipment, as well as lower levels of waste treatment in countries such as China and India. By contrast, developed economies in North America and Europe that were badly hit by the coronavirus produced relatively little pandemic plastic waste.The situation was worsened by the suspension or relaxation of restrictions on single-use plastic products globally. New York state’s ban on single-use plastic bags, which took effect in spring 2020, was only enforced that fall.“Better management of medical waste in epicenters, especially in developing countries, is necessary,” the researchers wrote, while also calling for the development of more environmentally friendly materials.“Governments should also mount public information campaigns not only regarding the proper collection and management of pandemic-related plastic waste , but also their judicial use,” said Von Hernandez, global coordinator of Break Free From Plastic, an advocacy group. “This includes advocating the use of reusable masks and PPEs for the general public … especially if one is not working in the front lines.”Much plastic waste enters the world’s oceans via major rivers, according to the researchers, who found that the three waterways most polluted by pandemic-associated plastic were all in Asia: The Shatt al-Arab feeds into the Persian Gulf; the Indus River empties into the Arabian Sea; and the Yangtze River flows to the East China Sea.”Given that the world is still grappling with COVID 19, we expect that the environmental and public health threats associated with pandemic related plastic waste would likely increase,The study said that the leading contributor of plastic discharged into oceans was medical waste generated by hospitals, which accounted for over 70 percent of such pollution. Scraps of online shopping packaging were particularly high in Asia, though it had a relatively small impact on global discharge.Modeling by the scientists indicates that the vast majority of plastic waste produced as a result of the pandemic will end up either on sea beds or beaches by the end of the century. In addition to becoming possible death traps for coastal animals, plastic buildup on beaches can increase the surrounding temperature, making the environment less hospitable to wildlife. And as plastic degrades over time, toxic chemicals may be released and moved up the food chain.

Most of us think supermarkets are responsible for plastic pollution

A pile of household waste at a landfill.Most people believe supermarkets and manufacturers are to blame for plastic pollution, a survey has found. In 2019, UK supermarkets produced 896,853 tonnes of plastic packaging – a slight decrease of less than 2% from 2018, according to Greenpeace.Supermarkets such as Waitrose have reduced plastic use and committed to increasing reusable packaging and unpacked ranges.But a survey by retail app Ubamarket found that most British shoppers think not enough is being done.Researchers found that 82% of shoppers believe the level of plastic packaging on food and drink products needs to be changed drastically.Read more: A 1988 warning about climate change was mostly rightMeanwhile, 77% believe that it is supermarkets and manufacturers that are causing the most plastic pollution, while 57% think that plastic pollution is the greatest threat to the environment.Will Broome, CEO and founder of Ubamarket, said: “While supermarkets have a long way to go, it is encouraging to see the use of single-use plastics beginning to be reduced in the UK.”This is helping us as a society take major steps towards creating a more sustainable future for the food retail sector, and retail across the board.”It is imperative that other retailers take heed of this and work quickly to establish their own sustainability goals and action plan.”Implementing mobile technology is one effective way for retailers to get ahead of the curve – not only can it improve in-store efficiency and provide access to useful data for the retailer.”Read moreWhy economists worry that reversing climate change is hopelessMelting snow in Himalayas drives growth of green sea slime visible from spaceBroome said Ubamarket’s Plastic Alerts feature allows users to shop “according to the recyclability and environmental footprint of different products, and enables the customer to scan packaging for information on whether it can be widely recycled or not”.Story continuesResearch published earlier this year found that thousands of rivers, including smaller ones, are responsible for 80% of plastic pollution worldwide.Previously, researchers believed that 10 large rivers – such as the Yangtze in China – were responsible for the bulk of plastic pollution. In fact, 1,000 rivers, or 1% of all rivers worldwide, carry most plastic to the sea.Therefore, areas such tropical islands are likely to be among the worst polluters, the researchers said.Watch: Philippine recyclers turn plastic into sheds

Provocative eco-art exhibition in S.F. forces confrontations with climate change

Sea levels may be rising, but Ana Teresa Fernández and her bucket brigade are doing what they can to combat it.Forming a 200-yard human chain on Ocean Beach, they drew 170 gallons out of the surf, hauled the sloshing saltwater off the beach and up to the old Cliff House restaurant, where it was carried into the dining room and muscled up a ladder to be poured into seven clear cylinders, all six-feet tall.

Living on Earth: Beyond the Headlines

Air Date: Week of November 5, 2021

stream/download this segment as an MP3 file

Some cement factories are collecting plastic waste from consumer goods businesses and landfills to use as fuel to fire their kilns, posing the risk of polluting air with toxic chemicals. (Photo: Xopolino on Wikimedia Commons)

This week, Host Bobby Bascomb talks with Peter Dykstra, an editor at Environmental Health News, about the public health hazards of cement kilns burning plastic waste as a source of fuel. And in California, Scripps Institution of Oceanography is building a 32,000-gallon simulated ocean to study the effects of climate change. Also, a trip back in time to November 1492 when native peoples introduced Christopher Columbus and his expedition to maize, which became a major food staple across the globe.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s time for a trip now Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org, and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. There’s an investigative story from Reuters. They’ve looked into cement kilns, cement kilns are everywhere, especially in booming cities in the developing world. They’re responsible for 7% of all the greenhouse gases emitted. So that’s a huge chunk. And right now, those cement kilns are looking for a new source of fuel to fire up the kilns and they’ve hit upon plastic waste. And that can be a bigger problem than any problem they may be solving.

BASCOMB: Hmm. Well, that makes sense. I mean, plastic is made with fossil fuels. So it’s, you know, pretty energy rich and there’s so much plastic waste out there. It’s free, or maybe even in some places might pay to have it, you know, burned like that. But of course, you know, it’s not too good for air quality now, is it?

DYKSTRA: Right, and there are consumer firms that are funding projects to send their plastic trash to cement plants. It’s a dangerous idea, given the amount of carcinogenic fumes that exists in those plastics, now burning straight, from, in many cases, the developed world to the developing world, to all of our lungs.

Cement factories are burning plastic to fire up massive cement kilns like the one pictured here. (Photo: LinguisticDemographer on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Yeah, I mean, looking at things like dioxins, heavy metals, carcinogens. I mean, it’s pretty, pretty toxic stuff.

DYKSTRA: And it’s been said that burning plastics in cement kilns doesn’t help lessen the landfill problem. It simply transfers the landfills from being on the ground to in the skies.

BASCOMB: Well, that certainly is a big problem. Well, what else do you have for us this week Peter?

DYKSTRA: It’s kind of a weird sci-fi sort of project. The Scripps Institute out in San Diego is building a 32,000 gallon tank that has a wind tunnel on top of it. And with all that, they hope to synthesize what happens in the ocean, and how the oceans can affect climate change.

BASCOMB: How will they do that?

DYKSTRA: There are wind currents brought in, water currents introduced mechanically into this tank, and we’ll see what happens as climate change begins to alter both wind and wave and current patterns. It’ll give a little bit more of an insight as to what lies ahead in our future, as climate change really takes hold in our oceans.

The surface layer of the ocean can tell scientists a lot when looking at climate change. That is one aspect researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography will study in their simulated ocean. (Photo: NOAA on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: So they can simulate climate change in this pool and sort of speculate what we’re going to be looking at then.

DYKSTRA: Right, and thanks for using the word pool because 32,000 gallons sounds like a lot, but it’s actually about 5% of what it takes to fill in a competition sized Olympic swimming pool.

BASCOMB: So it’s really not all that big then. It’s amazing what they can do in such a small space.

DYKSTRA: It is. Scientists can have fun with it and can give us some information that’ll help guide us through a particularly dangerous time in our environmental future.

BASCOMB: Indeed, well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: November 5, 1492. And we all know what happened in 1492. Columbus sailed the ocean blue. And on his subsequent stop to the Bahamas, Columbus went to Cuba in early November, and he was introduced to maize. That corn was brought back to Europe and has since become a global staple for both humans and livestock.

BASCOMB: Well, yeah, there’s so much to that. I mean, that the Columbian Exchange brought tomatoes and potatoes to Europe. I mean, imagine Italian food without tomatoes, but before that, they made do I guess.

Maize has become a food staple around the world after it was introduced from the New World to the Old World in 1492. (Photo: Balaram Mahalder on Wikimedia Commons)

DYKSTRA: And even though Columbus was a tip of the spear, coming from Europe, in the genocide of native peoples in the West, one other thing that was a gift so to speak, from North America to Europe was of course, tobacco. So it’s feed ya and kill ya, Mr. Columbus.

BASCOMB: All right. Well, thanks Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That’s ehn.org and DailyClimate.org. We’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there’s more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That’s loe dot org.

Links

Reuters | “Trash and Burn: Big Brands Stoke Cement Kilns with Plastic Waste as Recycling Falters” WIRED | “This Groundbreaking Simulator Generates A Huge Indoor Ocean” Read more about the Columbian Exchange

NJ legislation partially banning plastic straws now in effect

As of Nov. 4, all New Jersey restaurants and food service establishments are banned from providing single-use plastic straws unless specifically requested by customers, according to legislation passed by Gov. Phil Murphy and other lawmakers last year.

The ban is part of a statewide move to reduce plastic pollution originating from food and retail businesses.

ADVERTISEMENT