- New research suggests that plastic could contribute to ocean acidification, especially in highly polluted coastal areas, through the release of organic chemical compounds and carbon dioxide, both of which can lower the pH of seawater.

- The study found that sunlight enabled this process and that older, degraded plastics released a higher amount of dissolved organic carbon and did more to lower the pH of seawater.

- However, the findings of this study were conducted in a laboratory, so it’s unclear whether experiments conducted in estuaries or the open ocean would yield similar results, experts said.

The trillions of pieces of plastic currently roving through the global ocean are known to be an assault on life. Turtles get tangled up in discarded plastic fishing nets. Whales open their mouths to eat and unwittingly fill their stomachs with shopping bags. Filter-feeding fish and other organisms gobble up tiny plastic particles, poisoning themselves with the plastic’s toxins and passing that toxicity along to any animal that consumes them.

And now, new research suggests that plastic pollution could be harming the ocean in an additional way: by contributing to its acidification.

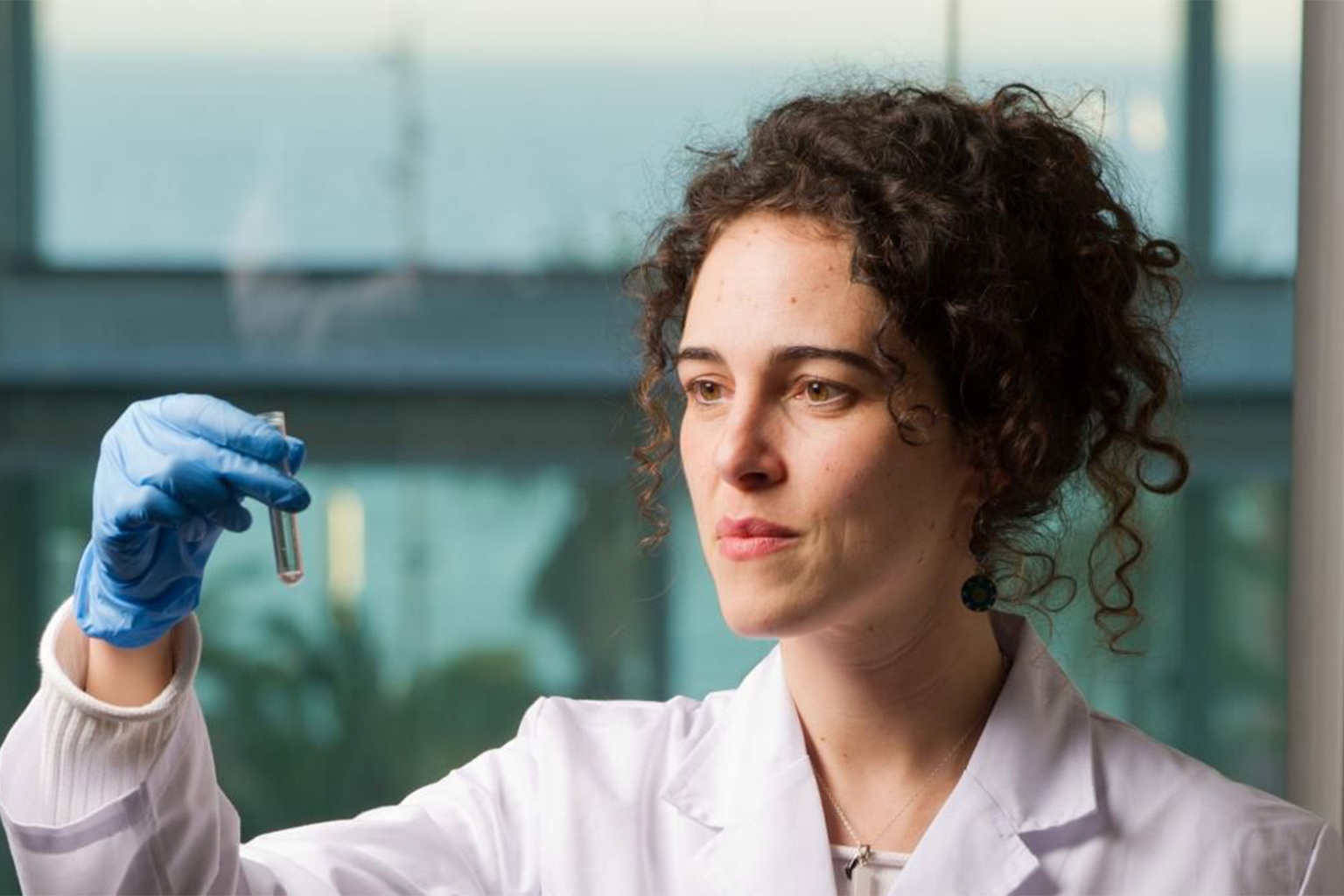

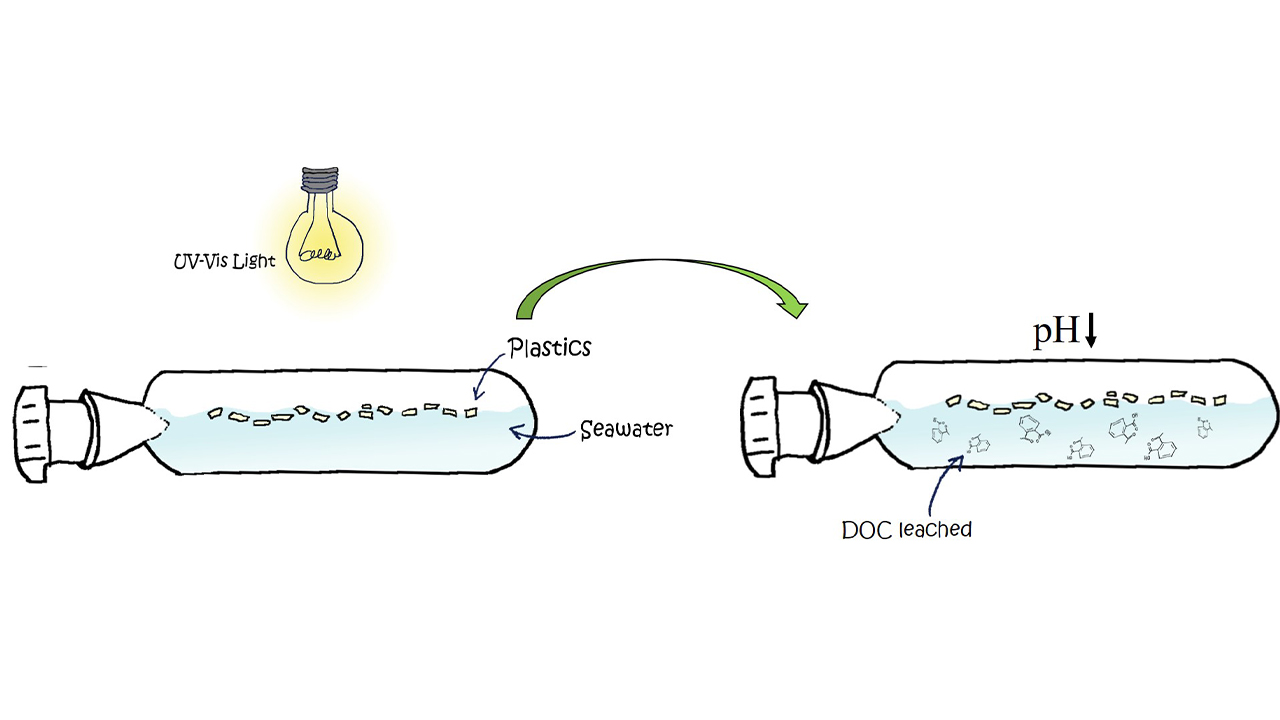

Through a series of laboratory experiments, scientists from the Marine Sciences Institute in Barcelona, known as ICM-CSIC by its Spanish acronym, found that when plastic — especially aged, degraded plastic — interacts with sunlight, it releases a cocktail of chemicals, including organic acids, into the ocean. Organic acids are known to lower the pH of seawater, causing it to become more acidic. In addition, the sun’s degradation of plastic can lead to carbon dioxide (CO2) release, which can cause pH to plummet further.

In highly polluted parts of the ocean, such as coastal areas, plastic could contribute to a drop of up to 0.5 pH units, which is “comparable to the pH drop estimated in the worst anthropogenic emissions scenarios for the end of the 21st century,” says Cristina Romera-Castillo, a postdoctoral researcher at ICM-CSIC and lead author of the study documenting the findings.

“The main factor producing the acidification is the greenhouse gas emissions that are dissolved in the ocean,” Romera-Castillo told Mongabay. “But I think it’s interesting to know that plastic is also contributing to the acidification.”

The world’s oceans absorb about 30% of humanity’s carbon emissions, which has resulted in a decrease in pH across the globe. Lowered pH obstructs the ability of marine organisms, such as corals, planktons, oysters and urchins, to build skeletons and shells out of calcium carbonate and to generally survive. The weakening of these calcifying organisms can impact other species that depend on them for food and habitat.

Like other climate change impacts, ocean acidification doesn’t occur uniformly across the world’s seas. But it’s estimated that, on average, the pH of surface waters has fallen by about 0.1 pH units. That may not sound like a lot, but scientists say this drop has already resulted in numerous and widespread changes across the global ocean. And things are set to get much worse if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise.

Some scientists even warn that ocean acidification represents a planetary boundary since it could significantly disrupt the functioning of Earth’s natural operating systems. According to the planetary boundaries theory, Earth’s ability to support life as we know it could be threatened if humanity pushes ocean acidification past a certain threshold — a limit beyond which the planet cannot cope with the changes and stresses humans place on it. When the impacts of high levels of ocean acidification interact with other Earth systems and processes, the resulting destabilization could place human life at risk.

While plastic pollution would not have nearly as much of an impact on ocean acidification as greenhouse emissions would, Romera-Castillo said it’s something to keep an eye on.

“There are many reasons why we should be concerned about plastic, and this is one more thing,” Romera-Castillo said. “This is not the only one or maybe not the worst, but it’s one more thing.”

Romera-Castillo and her coauthors conducted their lab experiments with new plastics, as well as aged plastic collected from Canary Island beaches. They placed the plastic waste inside glass bottles filled with seawater, and then exposed the bottles to ultraviolet light similar to the amounts occurring in sunlight. They found that the older plastic released a higher amount of dissolved organic carbon and did more to lower the pH of the seawater.

Right now, nearly 13 million metric tons of plastic reach the ocean each year, but this number could increase dramatically in the near future. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, plastic production could triple in the next 40 years, going from about 460 million metric tons in 2019 to 1.23 billion metric tons in 2060. More than likely, much of that plastic will end up in the natural environment, including the ocean. A UN plastics treaty which is currently in the works could potentially reduce those waste amounts.

Plastics, lumped in with roughly 350,000 other types of artificial chemicals in the global marketplace, are also categorized under another already breached planetary boundary. These so-called novel entities have become so pervasive as pollutants in the world — with new ones being engineered and introduced all the time — that they have violated the novel entity boundary’s critical threshold, with governments no longer able to keep up with evaluation or regulation of synthetic chemical risks.

Jason Hall-Spencer, a marine biologist and ocean acidification expert at the University of Plymouth, who was not involved in the new study, says the research shines a light on an important finding: that plastics do break down in seawater, releasing organic compounds and CO2 in the process.

“I think it’s important that people know about this phenomenon,” Hall-Spencer told Mongabay, “because what we’re often told is that plastics, once they get into the ocean, will last for millions of years, won’t break down or be there effectively forever.”

However, he questioned whether plastic would significantly contribute to acidification in the actual ocean. For instance, he suggested that waves and currents could mix the water and dissipate the impacts of plastic acidification. He also pointed out that ocean plastics are often encrusted with biological organisms that consume carbon dioxide and produce oxygen, which might also reduce the plastic’s contribution to acidification.

Furthermore, Hall-Spencer noted that a lot of ocean plastic ends up in places far from sunlight — like on the seafloor.

“It’s important that we know these plastics break down, and in doing so, they lower the pH,” he said. “But what’s needed as a next stage is verification that plastics in the ocean are lowering the pH.”

Stephen Widdicombe, a marine ecologist at Plymouth Marine Laboratory and co-chair of the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network, who was also not involved in the new study, said the findings are noteworthy since they indicate that plastic could be a potential driver of ocean acidification in coastal regions. But like Hall-Spencer, he said more research would need to be done to understand if these processes would happen outside the lab in real world situations and on a larger scale.

The study “does show us the importance of monitoring for multiple threats,” Widdicombe told Mongabay. “Often we get fixated on thinking, ‘Oh, we’ve got to go and monitor how much plastic there is there,’ or ‘We’ve got to go and monitor for ocean warming or deoxygenation,’ when really what we should be monitoring for is everything.”

Romera-Castillo said it would be much harder to conduct the same experiments in the ocean due to the multiple factors one has to consider, such as the respiration of microorganisms and the movement of the water. However, she said she and her team would like to try this in the future.

“This [study] is the first step,” she said. “Now, there are many questions opening up.”

Banner image: A coral reef in Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt. Lowered pH obstructs the ability of marine organisms, such as corals, planktons, oysters and urchins, to build skeletons and shells out of calcium carbonate and to generally survive. Image by Renata Romeo / Ocean Image Bank.

Citations:

Romera-Castillo, C., Lucas, A., Mallenco-Fornies, R., Briones-Rizo, M., Calvo, E., & Pelejero, C. (2023). Abiotic plastic leaching contributes to ocean acidification. Science of The Total Environment, 854, 158683. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158683

Persson, L., Carney Almroth, B. M., Collins, C. D., Cornell, S., De Wit, C. A., Diamond, M. L., … Hauschild, M. Z. (2022). Outside the safe operating space of the planetary boundary for novel entities. Environmental Science & Technology. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c04158

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin III, F. S., Lambin, E., … Foley, J. (2009). Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society, 14(2). Retrieved from https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/

Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a staff writer for Mongabay. Follow her on Twitter @ECAlberts.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.