Dr. Max Aung joins the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice podcast to discuss the dangers of some everyday chemicals to our health—and how regulation hasn’t kept up with these threats.

Aung, an assistant professor at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine and assistant director at the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice program, also talks about how pregnant people and babies are most vulnerable to these pervasive exposures.

The Agents of Change in Environmental Justice podcast is a biweekly podcast featuring the stories and big ideas from past and present fellows, as well as others in the field. You can see all of the past episodes here.

Transcript

Brian Bienkowski

All right, today’s guest hanging out is Dr. Max Aung, an assistant professor at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine and assistant director at the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice program. Aung talks about the mix of insidious pollutant exposures we all face, how these exposures impact the most vulnerable among us, and how policy can catch up to the ever growing list of concerning chemicals. Enjoy.

So Max, it is good to see you. But I will full disclosure for the listeners, I see you quite a bit now, you are part of the agents of change program, you are now an assistant director. And you were also part of our first cohort, and you wrote an essay about oil and gas development where you grew up. So I just want to start there, if you could tell me a little bit about what that experience was like, as a researcher being out there with your views and thoughts, what the reception was, to your article and a little bit about the work you’re doing now with us?

Max Aung

Yeah, so, you know, the article was such a great opportunity for me to reflect on the sort of environmental issues that are facing communities that have high oil and gas production. But it was also interesting, because having grown up there, you know, I’ve, I’ve had friends that work in the oil and gas fields, that’s like their first job out of high school, it pays really well. You know, it’s it’s basically the source of economic growth for a lot of folks in those communities. So, in my essay touched on that a bit – thinking about, you know, sort of how even though these have environmental impacts these different industries, there’s also this issue of like, how do you deal with folks that rely on this for their everyday lives? So I think, you know, when I wrote the essay, it was largely, you know, well received from I had some folks, you know, reach out to me, and, tell me that, that they found the article to be an important reflection on that balance. I’ve had, we got this article invited to be like in a undergraduate textbook chapter, which was really exciting, you know, that new scholars will be reading this as they think about creative writing and reflecting on environmental issues. And, yeah, so, you know, I think that’s sort of been a great foundation, as I’ve sort of navigated this next stage of my career and thinking about ways to incorporate communities and think about communities inputs, as we tried to shape policy, environmental policy. And so that’s been a huge factor, especially with some of my work at UCSF, which, you know, we can talk a little bit more about later on. In terms of the [Agents of Change] program, so I joined the leadership here in March. And it’s been really exciting because I’ve been working really closely with Dr. Ami Zota, you and Yoshi as well, and just thinking through different ways that we can engage existing scholars in the program, but also ways that we can, you know, galvanize the new cohorts towards different focus groups and thinking about how can we leverage that skill in terms of outreach and in terms of getting our Agents of Change fellows out there to you know, communicate with important stakeholders. So that’s been really exciting so far.

Brian Bienkowski

Good. And it’s so awesome to be part of the program and already a few years in have people like yourself who are part of it, who have now grown in your career and have new positions, and then come back. I mean for me when I started this, to already see people like you coming back and being a part of it after being in the first cohort, is just, it’s just wild how kind of fast time flies, but it’s been really excellent. And just for people listeners who maybe didn’t read your essay, so it was focused in Kern County, California, right?

Max Aung

Yeah, yeah.

Brian Bienkowski

You’re right. And I really appreciated the idea of thinking about the economic ramifications. I thought that was one of the aspects of your essays that was crucial when we think about weaning off oil and gas or just trying to get rid of polluting, polluting industries, thinking about the people that rely on these for their livelihoods.

Max Aung

Yeah, and it was, you know, it’s so great. Like, during our sessions, like in that first fellowship year, just, you know, getting the feedback from you, workshopping it with the other fellows was such a great experience. Because I felt like, I was consistently challenged to think about every single word I put into that essay, and like the impact, you know, and not being afraid to say, radical, social justice oriented things. And I did feel like that was such a great learning experience, sort of go through that exercise.

Brian Bienkowski

Well, that’s great to hear. And I hope future folks feel the same way. That’s definitely the spirit of the program. And so you went to University of California, Santa Cruz for your undergrad, and I believe you’re at University of Michigan over here for your masters and your PhD – I love Ann Arbor, is such a fun town. What drew you to public health? And how did you come to start researching environmental exposures?

Max Aung

Yeah, so okay, at Santa Cruz, I’d say I gained a really diverse set of research and education experiences. So you know, my undergraduate training was in molecular biology. And so I was just really drawn to some of my more advanced coursework around immunology, and thinking about the different mechanisms that underlie various different health conditions. And that’s was sort of, you know, my bedrock in terms of the coursework. On the other end, I was doing research in a stable isotope laboratory, in the ocean sciences department, which is totally, you know, not, you know, totally different in terms of science, but like, just a totally different direction in terms of how to apply scientific research. And so in that lab, I was working with an exciting team to reconstruct past sea surface temperatures over the course of several thousands of years. So we…the Paleo climatology lab is very focused on trying to understand past climate conditions so that we have data to inform future climate models. So there’s this, you know, this duality between the molecular Health Sciences and more environmental, climate-change focused research. And I think, you know, trying to think through these two different experiences, it was a little bit next, like, after undergrad, you know? I struggled a little bit with trying to find my path forward.

And after undergrad, I actually, I took two years, where I wasn’t in school, I was teaching full time for a STEM diversity program that focus on retaining undergraduates from historically marginalized backgrounds in the STEM fields. And so during that time, it gave me a little bit more breathing room to like, think through sort of what are my next steps, and, I got involved with the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science, so I was working with them in the summer. And through that, I started networking with all of these different – because they’re so well connected with all of these universities across the country – and, and through that I sort of got connected with different professors from different schools of public health. And as I was brainstorming through potential graduate training, and really tried to lean in on those background experiences. It became clear to me as I was learning about grad programs that something that would fulfill me is a blend of environmental research, plus Health Sciences, plus policy, right? And so I kind of converge it to like environmental health policy is like sort of where I was thinking. And then so when I was looking at different programs, you know, Michigan really stood out to me. They had a super strong Department of Environmental Health. And when I spoke to different faculty and different current students, it seemed like there was a lot of opportunity if you came in with environmental health to sort of branch out, and also gain skills in policy and some of the more data analysis, epidemiology heavy coursework.

So that’s the way, that’s the sort of path that brought me to Michigan. And at Michigan, you know, I don’t think any of this was planned, but I was able to receive this really exciting fellowship from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, it was called the Health Policy Research Scholars fellowship. And that really just amplified my health policy training. And it basically allowed me to integrate that type of training into my more science-heavy applications in environmental health. And so, you know, that’s sort of like my entry point into public health and the way I’ve been navigating it in terms of like, career trajectory.

Brian Bienkowski

What’s one place that you miss in Ann Arbor?

Max Aung

Oh. I love ramen. I think anybody that knows me really well knows that I’ll always, you know, go find like, the best ramen shop in any city I’m in. So there’s actually like a pretty, you know, delicious ramen place in downtown Ann Arbor called Slurping Turtle. And so that’s one place I miss. Where I was living most recently in Ann Arbor it’s in the middle of the campus and my home, or my former home. So like, you know, on the walk back, I had been known to just like, be like, alright, canceling dinner, cooking dinner, I’m just gonna get ramen.

Brian Bienkowski

Yeah, there’s, there’s a lot, there’s a lot in a town, that’s not huge. There’s a lot of super good food and good music and good places to get a drink. So, before we get on to how you’ve taken that environmental research and what you’re doing with it now, I wanted to ask you, what’s the defining moment that shaped your identity?

Max Aung

Oh, yeah, um, you know, I, so I think I can, you know, I could time travel back to a lot of different moments long, longer times ago, but I actually, I think, like in terms of something that’s really defined me, it’s like, for me, one of the experiences, most recently was, I was working at UCSF, and I had the opportunity to, basically, you know, co-lead my first big R1 proposal. And I think what was really exciting about this proposal was, I was focusing on basically trying to better understand mental health disparities among immigrant women, and focus on how environmental exposures are potentially impacting mental health disparities in this population. And I think what was like really pivotal for me as, as a scholar was, this is sort of a moment where, after I’ve developed all of the training, earned the PhD, got to this point in my career, I’m able to now develop research questions and research proposals that literally converge my identity as an immigrant scholar, but also focus on important salient problems that are impacting these communities. You know, I will say that grant hasn’t been funded yet. So we didn’t get it on the first try. But I, I will be persisting on it and trying again, and, reshaping it in different ways. But nonetheless, I still look back at that experience and think that it’s been a huge moment for me to I’m really just feel empowered to use my skills to, you know, and my lived experiences to pursue research that, that not very many folks are doing and I think is really important.

Brian Bienkowski

Yeah. And hopefully bettering science and shaping what environmental science looks like. And then take it one step further, hopefully making lives better, right?and in the communities you’re researching, or are looking into, in some way, having a positive impact. So that’s definitely a defining moment. I think that’s great. And hopefully it gets funded at some point.

Max Aung

Yeah, eventually I’m trying, I’m trying, you know, different ways to sort of get it funded. So crossing fingers.

Brian Bienkowski

So now you’re really broadly your focus now is on what we’re exposed to that impact our health and human development. So just just kind of a 10,000 foot view, walk me through some of the things that we’re exposed to that kind of keep you up at night? What are you looking at, exposure wise, that we should be concerned about?

Max Aung

Yeah, so. So, you know, historically, in terms of what I’ve done research on so far, I’ve focused a lot on endocrine disrupting chemicals. And this includes, for example, a lot of different chemicals found in plastics and different personal care products that you use on a daily basis, like lotions, shampoos. So you know, some chemicals include phalates, phenols, parabens, I’ve done a lot of research on these endocrine disrupting chemicals. Particularly, I’ve focused on how they’re influencing maternal health conditions, and potentially, what implications that has for infant health later in life. And sort of my core research applications in that space is to try to disentangle biological mechanisms, right? So that’s, that’s sort of in the bedrock of my PhD dissertation: identifying different biological pathways that might be affected by these chemicals, and trying to illustrate that in these different studies that that we’ve published, so that so that different scholars can learn about those mechanisms, and build on those when they think about risk assessment, and trying to identify high-risk scenarios with these high exposures and thinking about what pathways might be influenced by those exposures.

Brian Bienkowski

Can you talk a little bit about… so I think when we historically think about environmental pollution and things that harm us, we think of… let’s use lead for an example, the more lead that I’m exposed to, or that my nephew is exposed to, the more toxic it is. With endocrine disrupting compounds, it doesn’t always work that way, there can be very tiny amounts of exposure that that wreak havoc on the body and maybe at a higher exposure, it’s not the same. So can you talk a little bit about first of all, when we say endocrine disrupting compounds, what what we mean, and also kind of the challenge of identifying how toxic they are, because they don’t always behave like traditional toxics.

Max Aung

Yeah, that’s a good point. Yeah, so, just to set the baseline. So when we say endocrine disrupting chemicals, essentially, what that means is that these chemicals, especially, based on in vitro, mechanistic laboratory experiments, these chemicals have been shown to have properties where they can mimic hormone signaling, and they can essentially alter concentrations of different hormone production. And this has, I mean, even though we call them endocrine disrupting chemicals, this has wide implications for various different pathways, because not only can they affect the endocrine system and hormone production, but because the endocrine system is so intimately connected to the immune system, for example, these chemicals can also elicit inflammatory responses, so, they can, you know, cause immune cells to regulate these proteins that are involved with inflammation and this can have downstream effects on cardiovascular function on tissue damage. So, all sorts of different downstream effects. And that’s what makes these chemicals you know, very tricky to understand. Because if they’re affecting various different pathways, there’s all sorts of feedback loops that might be occurring. And disentangling those different feedback loops, and those different mechanisms is really challenging. In terms of the dosage, you know, what you’re saying is about the concentrations, and different levels of concentrations being important, that’s also a huge consideration, right? Because, you know, there’s some evidence that, you know, particular endocrine disrupting chemicals can have nonlinear relationships. So it’s like, even low doses can have effects, and maybe you might not see effects in the middle range, but then you might see effects in the higher range. And, you know, that’s really tricky, especially when you’re trying to investigate these chemicals in a large, prospective cohort, an epidemiology study, where you have a huge distribution of these chemicals, and the distribution might be different based on which study population you’re focusing on. So, yeah, all of those things are incredibly challenging. And, a lot of the research and collaborations I’m working on now, is these, you know, multi center, multi cohort investigations, where we’re integrating data across different birth cohorts. And that’s one of the ways that we can sort of tackle this problem is having a larger sample, a larger, diverse sample that we can have a better understanding of the different distributions of these exposures.

Brian Bienkowski

So, as you mentioned, a lot of your work is focused on babies, pregnant people, kind of fetal exposures. Can you talk about the specific vulnerabilities for these groups? And what we know about environmental exposures during this really critical window of development?

Max Aung

Yeah, so basically, a huge piece of my research is built on the developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis, which proposes that early life exposures can have, can be affecting key biological processes in utero, that can essentially influence the trajectory of infant development for many, many years. So this could be metabolic health, this could be neurodevelopment. So particularly, I’ve been focused on neurodevelopment, and that’s where my research program is shifting towards right now, in terms of my funded projects. And what we’re seeing so far is that, from preliminary data, that maternal biomarker profiles that we’ve measured in some of our pilot studies are associated with early measures of infant neurodevelopment. So after pregnancy. And those same biomarkers are also associated with environmental chemicals, such as the phalates from the consumer products. And so you know, our running hypothesis is that these chemicals are influencing different biomarker profiles in the mom during pregnancy, and that’s potentially influencing key neurodevelopmental features in the developing fetus, and that’s persisting into infancy. And so that’s one of the major pieces that I’m trying to work on. And so right now, we’re building on that preliminary work, and we’re expanding it into multiple different cohorts measuring these biomarkers. And the idea is that, from the study, we’ll be able to characterize these early mechanisms of neurotoxicity, potential neurotoxicity, but then also, hopefully use these biomarkers as you know, potential predictive tools that we can help to identify potential neurodevelopmental outcomes later in life.

Brian Bienkowski

So just so I’m clear that the basic idea is that the mother is exposed to, or the pregnant person is exposed to a compound, and you’re seeing… and by biomarkers, what do you mean, what are you looking at?

Max Aung

Yeah, so there’s all sorts of biomarkers that you know that we, that I’ve been researching over the past few years. But most recently, I’ve been focusing on these targeted bioactive lipids, so this includes, you know, parent fatty acid compounds that folks get from, you know, essentially their diet like arachidonic acid, linoleic acid. And these fatty acid compounds are essential, and you know, you need them for key biological processes. And as a component of their essential function and role in physiology, they are metabolized into secondary molecules that can stimulate different things like immune responses, cardiovascular function, they’re also important for, you know, kidney function. So, these secondary molecules are really key signals of biological processes. And so, when you measure them, and then you see that there are altered levels, or different concentrations associated with higher concentrations of phalates, then you start to be concerned, because, you know, that essentially suggest that perhaps, that the chemicals are influencing that metabolism of those bioactive lipids, and if they’re influencing that metabolism, they might be influencing all those downstream processes that I just laid out. And that’s, you know, that’s when we start to find that there might be a problem with that, because those downstream processes could be influencing the developing fetus.

Brian Bienkowski

So using a lotion that has too much phalates could make your child have delayed development, maybe some kind of behavioral issues. I mean, are these the kinds of downstream impacts you’re looking up?

Max Aung

Well, we’re trying to disentangle that. It’ still very early stages in terms of those outcomes, but some of my colleagues in that I collaborate in these cohorts have found associations with dilates and altered infant neurodevelopmental parameters. And so we are seeing evidence so far that there are some associations. And so now that we’ve seen those relationships with dilates and neurodevelopment, this next stage that I’m proposing is trying to find these linking pathways, with these bioactive lipids that might be explaining some of these relationships.

Brian Bienkowski

And of course, as humans, we’re all eating perhaps produce that has pesticides, we’re putting on these lotions, we’re eating out of plastic containers, we’re walking outside where there’s heavy traffic, so we’re exposed to mixtures of pollutants all the time. So can you outline, you know, first, why that’s a challenge for researchers like yourself, and how folks like you try to best capture what these mixtures might be doing to us, or disentangling them? If that’s what you’re doing.

Max Aung

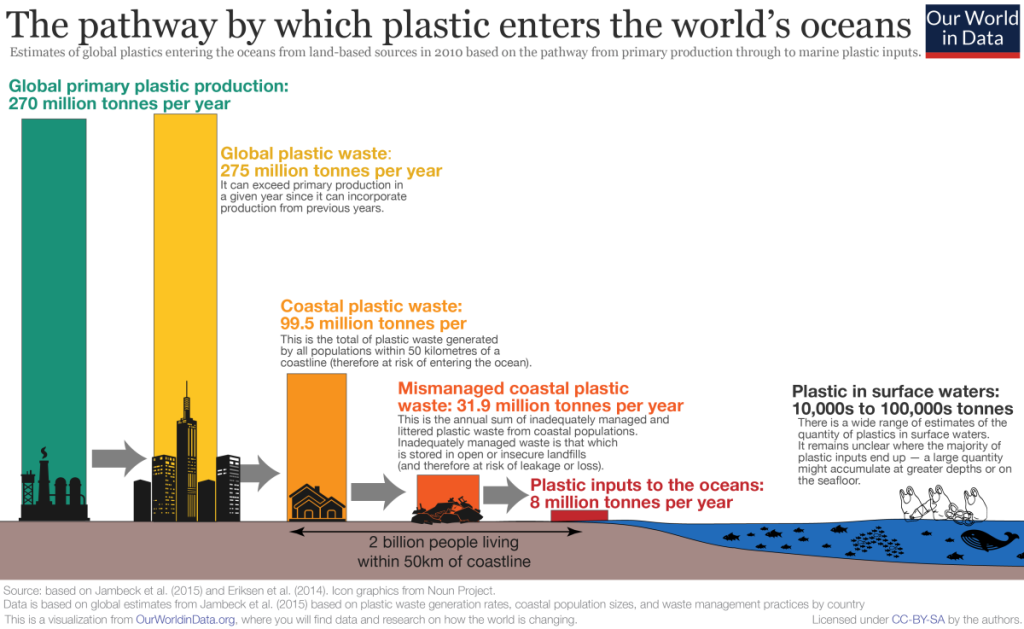

Yeah. So yeah, so thanks for bringing that up. You know, there’s, there’s hundreds of thousands of chemicals that were exposed to, and like you said, pesticides, and some pesticides have been shown in mechanistic models to be neurotoxic. So when you think about, you know, the cumulative exposures of pesticides, phthalates, toxic metals like lead, and, what is so challenging about understanding any single chemical class is that they’re not acting alone, right? You have these different exposures that are also influencing these biological pathways. And they’re also, through that mechanism, potentially influencing those outcomes like neurodevelopment. And so you know, what I’d say, in that space of disentangling the mechanisms. I think what’s really challenging is, you know, one of the studies I published like a couple of years ago is we looked at like four different chemical classes, you know, dilates, included toxic metals included, and we saw that they’re having these, in some cases, divergent associations with these biological pathways and these biomarkers, and so when you see divergent pathways, it’s really tricky because it’s hard to understand what that implication is in terms of the downstream effects. Like are they acting sort of against each other? like antagonistically? Is this an issue of temporality, where we’ve only measured the exposures once and the biomarkers once so we’re not capturing the bigger picture, right? So there’s a lot of unanswered questions in terms of like these mixture effects. But I think, in that chaos and confusion of all these different divergent relationships, I think there’s something really compelling in terms of this really emphasizes the need to look at chemicals as a whole mixture, because you’re going to miss things if you don’t, right? if you focus on just one chemical class, you’re really going to miss the fact that other chemical classes are having. And it’s, it’s really not conducive for risk assessment, you know, when you think when you’re ignoring those different chemical classes. And so, you know, in terms of taking the risk assessments and thinking of downstream policy implications, I think it’s really critical that we start to evolve from this one chemical at a time policy approach and thinking about all of these chemicals, cumulatively.

Brian Bienkowski

So that leads me nicely into my next question, and maybe that’s in part your answer. I was thinking about, I’ve been, personally, I’ve been writing about BPA for more than a decade now. And the bad news keeps coming. And the studies keep finding impacts, whether it’s animal studies, or correlational, human epidemiological studies, and it’s still not regulated, right, nothing happens. And one of the things I realized as a journalist pretty early on that I think is was surprising to me, and I think it’s surprising to other people is that everything on the shelf isn’t tested to the extent that you think it is. So, you know, we you’re talking about phalates and things that are probably in my shower right now. So, where’s the regulation failing? So maybe one one aspect you mentioned, is not looking at things as classes rather trying to look at them individually, but what else? What else could we or should we be doing?

Max Aung

That’s a, that’s a big question. You know, I think there’s so many different things we could be doing better. But, you know, one of the things for sure is, you know, in addition to looking at the cumulative effects is thinking about better capturing different routes of exposure and integrating that holistically – especially thinking about different historically marginalized communities as well, because there is historic exposure that needs to be accounted for in marginalized communities. So, you know, some communities are exposed to not only the phalates, but high levels of air pollution, toxic lead, there’s PFAS in the drinking water. So thinking about historical exposures as well is really important, because that really contextualizes the current state of the problem that those communities might be facing. Whereas if you just look at the chemical class in isolation, without thinking about those historic exposures, you’re going to underestimate the risk that those communities are experiencing.

Brian Bienkowski

What would you tell someone who’s an expecting mother?

Max Aung

That’s, you know, I think, what I would tell them is that, you know, well… I think in general, what I would tell folks is that a lot of the solutions, the really big impact solutions are going to come at the regulatory policy level, we can try to limit our exposures as a consumer by, you know, not using this product or that product. You know, avoiding different products, but that’s really so marginal in terms of exposure reduction. I think the onus should really be on regulators and industry to not use these chemicals and to use safer alternatives or if some of these chemicals are not essential, basically, yeah, like they shouldn’t be produced. So in terms of what I tell folks when they asked me about reducing things like, in addition to, you know, avoiding certain products, I would say, it’s really, also going to take a lot of civic engagement to push policymakers to make responsible decisions on reducing these harmful exposures. That’s really where the big-impact, exposure reduction is going to come from. And so, you know, I think that’s where we really have to invest our energy and our effort, as scientists as activists, and sort of pushing policymakers and industries to sort of do better.

Brian Bienkowski

Was there an “aha!” moment for you or something that you learned when you were researching these exposures that you don’t think most people would know about? Something kind of surprising, interesting, shocking.

Max Aung

You know, I think like, for me, it’s, it’s been… Well, the first part was just seeing how many chemicals we’re exposed to. It’s pretty alarming. And there’s estimates that there’s like, hundreds of thousands of registered and, you know, thousands of unregistered chemicals too, and that is really problematic, because as a scientist, it’s really, it’s really challenging to investigate the health effects of these chemicals, when there’s like such a large mountain of chemicals. And so I think that was been sort of a huge moment, in terms of the way I think about the problem. And it’s also compelled me to not only investigate them, to the best I can with these epi cohorts –we’re very limited in those cohorts on what we can measure, right, just because of costs– So that’s compelled me to, you know, in addition to focusing on those, also think about how we can drive policy forward. And one of the things I’ve been working on in my role at UCSF, in my past, while at UCSF and I’m still carrying it forward, is thinking about developing a framework to inform policy action when there’s limited research, and to sort of, how can we drive decision making forward? so that we can reduce exposures without having to necessarily conduct these large epi cohorts that will take many, many years to do. So finding that balance has been really tricky. And that’s, you know, something sort of that I’ve been focusing on a lot recently, and it’s really great in terms of bridging my policy bug right into my science hat.

Brian Bienkowski

I wonder if that might be the answer to my next question. I was thinking about a lot of everybody in the Agents of Change program, there’s a, there’s a real importance placed on using your research to spur positive change in communities. And I think in some instances, I’ve seen this with reporting, when we report on a fence-line community, and there’s a power plant, it’s a very clear link: these people are being harmed by this thing, how can we make that known and spur action? It’s easy, it’s local. Whereas what you’re looking at is so ubiquitous and big. And really, we’re all exposed to these compounds and in some communities more than others, but being such a big, unwieldy problem. I’m wondering how you go about trying to make that change happen?

Max Aung

Yeah, so that’s definitely an ongoing workshopping and brainstorming process. In terms of like, how I’ve been approaching it with my collaborators at UCSF, we’re developing thi framework for Environmental Health Policy. And the goal of the framework is to develop a process, a very transparent process for evaluating scientific evidence to inform policymakers to take action on an environmental contaminant. And so in that process, it requires the integration of key decision criteria, right? Like how will you balance the costs and benefits of an intervention? How do you balance environmental injustice and the potential to essentially push back against systemic racism? you know, how can the intervention do that in terms of environmental hazards? And in this process, like, I think the way that we’ve sort of started to approach it is bringing in key stakeholders, from NGOs, from the government, from different community organizations, and really listening, trying to listen on their input. And so that’s one of the most recent things we did in this project: [it] was to bring together a workshop of different key stakeholders. And so now going forward, you know, we’re synthesizing through that information. And as we develop future case studies and applications for our policy framework, I think, will continue to sort of bring in community engagement and really trying to get their input every step of the way, so that we’re impacting a potential intervention with their ideas in mind and very integrated into how we’re approaching the potential intervention or recommendation.

Brian Bienkowski

I remember talking to Dr. Reginald Seeley, who who spoke to the Agents of Change at some point. And he mentioned when he worked on The Hill for a little while, how incredibly busy policymakers are. This idea of you doing some of the work for them and taking the studies and running them through this project and giving them different outputs of “this would do this, And this would do that. And there’s benefits here cost saving here,” I think is brilliant.

Max Aung

Yeah, absolutely. It’s a big, it’s a big hill, but I think that, you know, I’m optimistic. And I think we have a stellar team of collaborators. And we’ve brought together a great steering committee to help guide us. It’s really exciting. So I’m hopeful that we can continue that work and really influence policymakers in the future.

Brian Bienkowski

Excellent. I just have a couple more questions for you, Max. And this has been a really good time it is there anything else that you want to mention that you are optimistic about? Some of these topics are just heavy. What else out there gets you excited or hopeful?

Max Aung

Yeah, I think, you know, in terms of like, the science, I am pretty, I’m getting optimistic about how some of the funding opportunities that have been announced through the NIH, I’m starting to see more and more emphasis on important research that has implications for environmental justice. And not just NIH but also the EPA. There’s an environmental justice intent in some of these opportunities. So, I’m cautiously optimistic that they can influence positive change and promote social justice. You know, and hopefully, the folks that get these different funding mechanisms can incorporate community input, and really drive environmental justice forward. And I think there’s also a lot of potential in terms of a lot of initiatives that the Biden administration is doing, in terms of trying to integrate social justice into a lot of their regulatory frameworks. And so I think, I’m optimistic about that. I really hope it can be sustained after like the midterm elections, and hopefully in the next four years, but, we’ll see.

Brian Bienkowski

of living. Yeah, article, political realities. Yeah, unfortunately, sometimes But you know, I what I will say is the fact that there is an awareness, you know, easy for me to say I’m not a member of a community that is dealing with these things. But I think the fact that there is awareness right now is a positive step in itself. And hopefully that continues to bring about change. So Max, I have three rapid fire questions where you can just give me one word, or phrase and then we can, we can move on, get me out of here and the rest of your day. So one of my all time favorite movies

Max Aung

Moulin Rouge

Brian Bienkowski

When I have downtime, I am most likely

Max Aung

Cycling outdoors.

Brian Bienkowski

Oh, gosh, me too. I’m taking one as soon as we get done here. And I cannot I cannot start my day without

Max Aung

Coffee.

Brian Bienkowski

Perfect. We are two for three on matching each other there. And Max. My last question, what is the last book that you read for fun?

Max Aung

I just started reading this book called “On Earth we’re briefly gorgeous.” And I haven’t finished it yet. So I’ll let you know what when I finished it, but so far, it’s really poetic.

Brian Bienkowski

And who is the author on that?

Max Aung

I hope I’m pronouncing their name right. Ocean Vuong.

Brian Bienkowski

Yeah. “On Earth We’re briefly gorgeous.” I love the title.

Max Aung

Yeah, it’s a beautiful title. And their background is largely in, you know, in creative writing and poem. So it’s got that sort of that vibe in there quite a bit.

Brian Bienkowski

Excellent. Well, Max, thank you so much for taking time today. I really mean it that I am so excited that you’re part of the team and I get to see you and talk to you and brainstorm with you on how to grow this program. So thank you so much for today.

Max Aung

Yeah, thanks so much for inviting me.