Two years ago, efforts to kick the country’s plastic addiction were on fire. Municipalities around the country were implementing plastic bag taxes, while mainstream shoppers embraced reusable grocery bags and flocked to the bulk aisles for foods like beans and nuts.

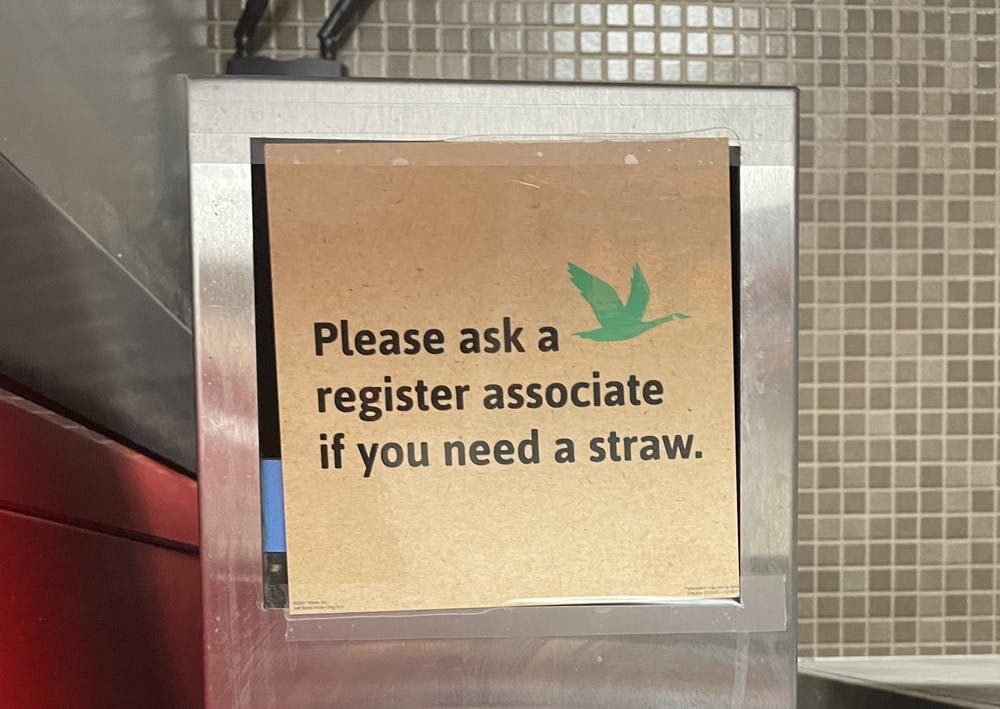

However, all that came to a halt when stopping the spread of COVID-19 became the country’s top priority. Almost overnight, grocery stores closed their bulk-shopping sections, coffee shops stopped filling reusable coffee mugs, and individually wrapped everything took center stage.

Now, signs are emerging that the fight against plastic is getting back on track. One of the most notable of those signs came from Kroger last month, when the nation’s largest grocery chain announced it was expanding an online trial with Loop, an online platform for refillable packaging, to 25 Fred Meyer store locations in Portland, Oregon.

While consumer reuse models “got punched in the face” by the pandemic, Loop’s Tom Szaky said the demand is still there, and mainstream grocery stores are going to need to find a way to meet it.

Kroger plans to offer a separate Loop aisle in these stores. The products, which will include a mix of items in food and other categories, can be bought in glass containers or aluminum boxes. When they’re empty, customers return the containers to the store to be cleaned and used again. Originally scheduled for this fall, the launch has been postponed to early 2022 because of supply chain challenges, but a spokesperson said they will continue to work with their brand partners to consider items that can be added to expand the program over time.

The partnership is a heartening sign after a tough year, said Tom Szaky, CEO and founder of TerraCycle, the company behind the Loop initiative. “Overall, I was very worried that the pandemic would shift the conversation away from waste,” Szaky told Civil Eats. “It didn’t slow down. In fact, the environmental movement’s only gotten stronger.” While consumer reuse models—reusable grocery bags, refillable coffee mugs—“got punched in the face,” he said, it was mainly because retailers stopped allowing them for safety reasons.

And while Loop’s growth was slowed by the pandemic, it was for the same factors that upended many companies’ plans—not because interest was drying out, said Szaky. The demand is still there, he adds, and he’s bullish on the idea that mainstream grocery stores are going to need to find a way to meet it.

The Kroger–Loop partnership could be the first true test of this theory. It’s the latest in a steady string of new partnerships for Loop, but until now all of the company’s U.S. packaging partners have been in other categories, such as cosmetics and cleaning products. Loop does work with a number of food companies outside the country, including Woolworths in New Zealand, Tesco in the U.K., Aeon in Japan, and Carrefour in France. Szaky says they’re also working with a grocery store in France to bring reusable packaging to fish and meat. Loop, which also works with Walgreens in the U.S. and fast food chains McDonald’s, Burger King, and Canada-based Tim Hortons, expects nearly 200 stores and restaurants worldwide to be selling products in reusable packages by the first quarter of 2022, according to the Associated Press, up from a dozen stores in Paris at the end of last year. Some experts in the space are convinced that more will follow.

“It’s just a matter of time before other companies come on board,” says Colleen Henn, founder of All Good Goods, a plastic-free pantry subscription business based in San Clemente, California that sells food in reusable glass jars and paper bags. “Once somebody does it, people start to see, ‘Oh, avoiding single-use plastic is] not that complicated.’ Because it’s really not.”

She would know. Henn didn’t spend the last year adapting her business; she first launched her seemingly improbable business model during—and really because of—the pandemic. She had grown frustrated that the country’s waste-reduction initiatives were falling by the wayside. “I went online and tried to find a store that shipped food to your door without plastic, and I couldn’t find it. So I created it,” said Henn.

All Good Goods specializes in pantry goods like beans and pasta, nuts and dried fruit, and growth has been strong and steady since the launch. She increasingly fields phone calls from other stores looking for advice on how to avoid plastic in their operations, and as she engages with more companies, she’s optimistic that she will have a trickle-up effect within the industry. “I reach out to brands [we’re considering carrying] and see what their wholesale options are; if they’re not paper-based, if they’re not backyard-biodegradable, we move on,” said Henn.

Major funding for Living on Earth is provided by the National Science Foundation.

Major funding for Living on Earth is provided by the National Science Foundation.

Socially and environmentally sustainable investing.

Socially and environmentally sustainable investing.

Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet.

Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet.

Energy Foundation

Energy Foundation