<div class="article-block article-text" data-behavior="newsletter_promo dfp_article_rendering " data-dfp-adword="Advertisement" data-newsletterpromo_article-text="

Sign up for Scientific American’s free newsletters.

” data-newsletterpromo_article-image=”https://static.scientificamerican.com/sciam/cache/file/CF54EB21-65FD-4978-9EEF80245C772996_source.jpg” data-newsletterpromo_article-button-text=”Sign Up” data-newsletterpromo_article-button-link=”https://www.scientificamerican.com/page/newsletter-sign-up/?origincode=2018_sciam_ArticlePromo_NewsletterSignUp” name=”articleBody” itemprop=”articleBody”>

After four years of an agenda that favored polluters, a new day is dawning at the Department of the Interior. In March, communities across the country rejoiced in Secretary Deb Haaland’s historic confirmation to lead the biggest and most powerful land management agency in the country. Now, she’s taking the opportunity to pursue real reforms of the broken oil and gas leasing system that has prioritized fossil fuel CEOs for too long. The possibilities for a cleaner, more equitable future are before us.

This will not be easy, but it is possible. Already, the Biden administration has turned its attention to the broken federal oil and gas leasing program by pausing all new leases on public lands. While this pause is in effect, I implore Secretary Haaland and the Department of the Interior to undertake an environmental justice review of the leasing program in order to address the racial discrimination within oil and gas operations.

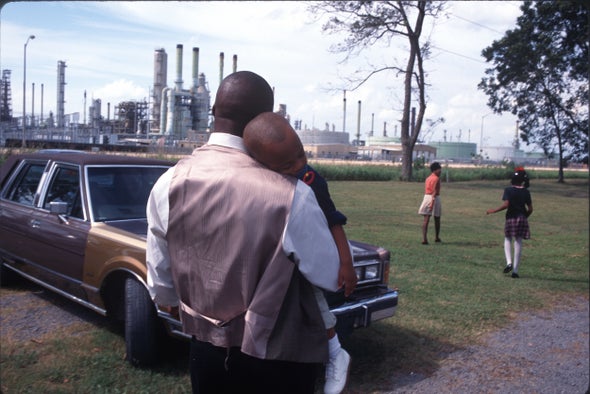

This review is an important first step in recognizing the injustices in the system, listening to the people who are impacted by them and hearing what their ideas are for reform. As the executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice (DSCEJ), I work with communities along the lower Mississippi River, between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, that are harmed by environmental racism and face serious health threats from the more than 100 polluting facilities that release a deadly cocktail of poison each day. Throughout my nearly 30 years in this work, I have witnessed how the oil and gas industry has dominated the Gulf Coast region at the expense of Black communities, engulfing our neighborhoods with massive amounts of toxic pollution from oil refining and manufacturing.

This pollution flows through our backyards, school grounds and recreation centers, threatening our access to clean air and water and jeopardizing our health. But all too often, the communities hit hardest by these dangers are ignored and left out of the conversation. We deserve better, and this leasing pause is the opportunity to give Secretary Haaland the chance to hear from us and to center justice and equity in reforms of the oil and gas program.

The environmental injustices our communities face are numerous. In 2019, the Environmental Protection Agency published a report that found the petroleum sector released over 11 million pounds of pollution in 25 Louisiana parishes, with many of these facilities operating in close proximity to Black residents. Within this pollution were chemicals widely known to cause cancer and damage heart and lung functions, making it difficult to breathe and often leading to premature death. And now, as studies show that air pollution exacerbates the impacts of the COVID-19 virus, the threat that oil and gas facilities pose to our communities is only being magnified.

Unfortunately, air pollution is not the only concern. In coastal communities, redlining, oil spills and offshore drilling add to racial inequality. Following the BP oil drilling disaster, massive amounts of oil waste were disposed of in landfills next to Black communities, jeopardizing our water supplies. And as offshore drilling continues, our coastlines are deteriorating, leaving many areas without natural defenses to extreme weather events. To make matters worse, greenhouse gas emissions from the oil and gas industry are massive contributors to the climate crisis, which disproportionately affects our communities where floods, heat waves and other climate-induced disasters have become the norm.

Communities in the Gulf Coast region are advocating for equitable energy solutions that create new, good-paying jobs, keep our air and water clean and our climate safe—but we need the support of the federal government. The existential threat of climate change and the troubling health disparities in Black communities are among the egregious impacts of reckless oil and gas development.

President Biden has made it clear that reforming the leasing system is a top priority for his administration. Now, with the leasing pause presenting an opportunity to complete a comprehensive review, it is imperative that the administration and Secretary Haaland join forces with us to prioritize an environmentally and economically just transition from fossil fuel development. We are counting on it.

This is an opinion and analysis article.