CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas—Five years ago, when ExxonMobil came calling, city officials eagerly signed over a large portion of their water supply so the oil giant could build a $10 billion plant to make plastics out of methane gas.

A year later, they did the same for Steel Dynamics to build a rolled-steel factory.

Never mind that Corpus Christi, a mid-sized city on the semi-arid South Texas coast, had just raced through its 50-year water plan 13 years ahead of schedule. Planners believed they had a solution: large-scale seawater desalination.

According to the plan in 2019, the state’s first plant needed to be running by early 2023 to safely meet industrial water demands that were scheduled to come online. But Corpus Christi never got it done.

That hasn’t stopped the city and its port authority from pursuing broader plans to build out a next-generation industrial sector around Corpus Christi Bay and make this region a rival to Houston, home to the nation’s largest petrochemical complex, 200 miles up the Gulf Coast.

As efforts to cut carbon emissions fall desperately behind the timetables established in decades’ of global climate accords, Corpus Christi is planning a massive expansion of its hydrocarbon sector, aimed at delivering oil and gas from Texas’ shale fields to global markets for decades to come.

All that’s missing is the freshwater. Now the commitments city officials made over the past five years are coming due. Exxon’s plastic plant started operations this year and will eventually consume 25 million gallons of water per day, even as the region’s water plan foresees demand exceeding supplies in this decade.

A mural depicts sea life on a chemical tank at a Citgo refinery. Credit: Dylan Baddour

This summer, severe drought and heat pushed Corpus Christi into water use restrictions. Yet the desalination plans remained years away from completion, hung up on questions from state and federal environmental regulators—the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency—over the ecological consequences of dumping hundreds of millions of gallons of salty brine per day into Corpus Christi Bay.

“I would love nothing more than to get right in front of their faces—the state, TCEQ, EPA, all of those agencies—and say, ‘Hey people! Do you realize that we need this permit now? We provide water for 500,000 people,” Corpus Christi mayor Paulette Guajardo told the city council in July, answering complaints over years of delays. “This is of urgency. We have to have this permit.”

Today the pursuit of desalination has become an increasingly desperate race to meet incoming demands. The number of plants proposed for Corpus Christi Bay has grown to five—two for the City of Corpus Christi, two for the Port of Corpus Christi and one for a private polymer manufacturer.

Last month, the TCEQ issued its first wastewater discharge permit to a plant proposed by the port, despite a challenge from the EPA signaling what could be a long legal fight ahead.

Regulators and scientists worry that each plant’s discharge of tens of millions of gallons of hyper-salty wastewater per day could disrupt major reproductive cycles for a host of aquatic species, which rely on the half-salty waters of the coastal bays for larvae to mature.

All together, environmentalists say, the five plants’ discharge, coupled with the water pollution and ocean freighter traffic from the industrial boom they would unleash, may constitute a near-fatal blow for life in the bay, whose once-teeming ecosystems have nursed communities on its banks since long before Corpus Christi.

While plant developers have put forth analyses showing their discharge won’t affect ambient salinity or wildlife, Paul Montagna, a department chair at the Harte Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M University in Corpus Christi, doesn’t buy it.

“I don’t see how you can add brine to a salty system and not increase the salinity, I just don’t understand how that could happen,” he said from his corner office at the university, with two-story windows looking out to the bay. “I’ve read the engineering studies and I just don’t get it.”

Montagna agrees that Corpus Christi needs desalination, he just wants the brine piped a dozen miles offshore and released into the open Gulf instead of the shallow, almost stagnant bay. The idea is supported by scientists but dismissed by developers as too expensive.

Other activists hope to block desalination altogether with an aim to hold up the buildout that has unfolded here in recent years, fueled by a spate of new pipelines carrying oil and gas from the Permian Basin and the Eagleford Shale since 2010, and by Congress’ lifting of the oil export ban in 2015, which have made Corpus Christi the nation’s top port for crude exports. One piece remains for the growth to continue.

“That’s the chokehold,” said Isabel Araiza, a professor of social work at Del Mar College and founder of a group called For the Greater Good. “In order to bring heavy industry in they’re going to need water.”

Speaking Out Against Desalination

Six days after Exxon accepted Corpus Christi’s offer of water in 2017, the city authorized an application for state funding to develop preliminary plans for a seawater desalination plant.

When Steel Dynamics came seeking water in 2018, Corpus Christi offered another 6 million gallons a day, citing “plans for additional water sources in the planning and implementation phase.”

But that wasn’t exactly true. The preliminary plans had yet to be shared with city council and implementation remained years away at best.

A great blue heron flies past the Corpus Christi skyline. Credit: Dylan Baddour

When the plans were presented in 2019, they noted Exxon’s demand scheduled for 2022 and Steel Dynamics’ after that.

“Large increases in water demand are projected to occur in 2022,” the city’s presentation said. “Based on supply and demand projections, the first desalination plant needs to be operational (supplying water) in early 2023.”

The council voted unanimously to adopt the plan. Activists quickly pushed back. Araiza, the leader of For the Greater Good, stood outside Fry’s Electronics on Black Friday speaking out against desalination.

“It’s for industry, not for us. And we pay for it,” she remembers telling shoppers.

Araiza, whose family has been in Corpus Christi for a century, hoped to engage the public in such big decisions about the city’s future, which she said were too often made by small cliques of business elites for their own benefit. Her family had been in the area for a century. On her dad’s side she was the first generation in memory not to pick crops.

Growing up in the 1970s she rode buses across Corpus Christi as part of belated integration of white and Hispanic schools. She earned a Ph.D. from Boston College, then returned home to organize and teach.

“What’s happening with industry and water is symptomatic of a bigger problem,” she said. “Our way of life is problematic: consumerism, disposable products, single use plastics.”

Araiza joined a budding activist movement that was heaping challenges on the desalination plans, forcing a slate of environmental permit applications through tedious administrative reviews.

Council member Mike Pusley, a retired petroleum geologist and former Exxon employee, was not impressed with the city’s progress. At a meeting in April 2021, he told the Corpus Christi water department its original plans, long delayed, were no longer sufficient.

“I can assure you that within the next five years, you’re going to have several Exxons here, and you’re not going to be ready with a plan. We’re not going to be ready. We’re not going to be ready at all with the water,” he said.

‘How Did They Get Ahead of Us?‘

While desalination plans fell further behind, the water supply was shrinking. The city’s reservoirs dipped to 40 percent of capacity as drought and heatwave grew acute this summer, prompting new restrictions and $500 fines for anyone caught running a sprinkler more than once per week.

Meanwhile, the Port of Corpus Christi Authority had jumped into the race and claimed a clear lead, threatening the city’s historic monopoly on the regional water supply.

Fisherman at a jetty in the Gulf of Mexico at North Padre Island, across the bay from Corpus Christi, on a Wednesday afternoon in October. Credit: Dylan Baddour

“It’s taking way too long for this to happen. The port has out-warriored us, they’ve out-lobbied us, they’ve out-engineered us,” Pusley said. “How did they get ahead of us? We’re the regional water supplier.”

“They spent more money on lawyers and lobbyists,” responded Mike Murphy, chief operating officer for the Corpus Christi water department, who moved to the city in 2021.

(The port’s lobbyists and lawyers wouldn’t secure their first controversial permit, issued by the Industry-friendly TCEQ over the EPA’s objections, until September.)

“This drought we’re in right now, there’s no solution for it but conservation,” said Corpus Christi manager Peter Zanoni, who moved to the city in 2019, to the council.

Conservation, however, only applies to residents in Corpus Christi. According to a 2018 city ordinance, high-volume industrial users can pay $0.25 per thousand gallons consumed for exemption from restrictions during drought. Most pay it. While citizens face fines for sprinkler use, large facilities continue consuming millions of gallons per day.

A Proliferation of Energy and Industrial Projects

The fight for water comes at a time of rapid industrial growth around Corpus Christi.

In the last five years, Valero and FlintHills expanded their refineries. Cheniere Energy built the region’s first export terminal for liquified natural gas and plans to double its output. Vostalpine built a plant that makes iron briquettes. Three huge, adjacent crude export terminals have cropped up on the bay, operated by Enbridge Inc., FlintHills and Buckeye Global Marine Terminals. Elon Musk wants to build a lithium refinery.

Dolphins surface while a crude tanker docks at an Enbridge export terminal on Corpus Christi Bay. Credit: Dylan Baddour

“When we started being able to sell oil [abroad], the amount of new industry that moved to this area was phenomenal,” said Montagna. “I think there has been more change in this region in the last four years than there had been in the last 20.”

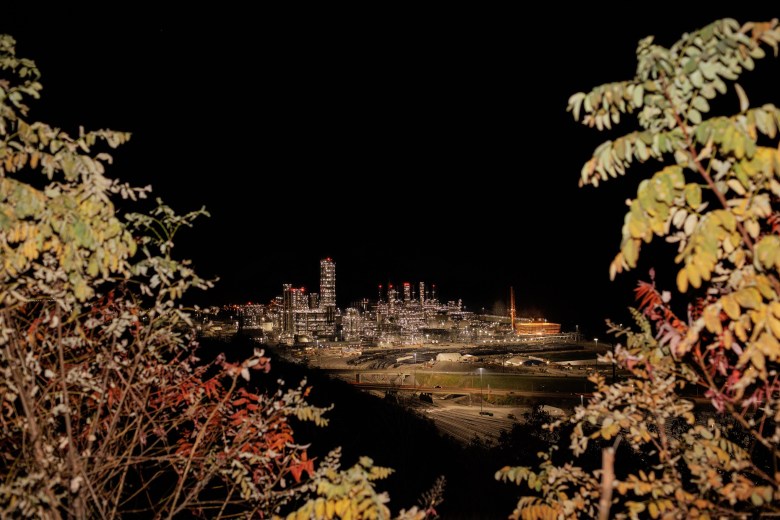

This year, Exxon opened its plastics plant, turning ethane, a form of natural gas, into ethylene and polyethylene, building blocks for plastics, on 1,300 acres across the bay from Corpus, in San Patricio County.

When the plant uses its ground flare—sportsfield sized units for burning off chemicals—Elida Castillo can see the sky glow orange from her house in the small town of Taft, about eight miles away, near a cemetery where her great, great grandparents are buried. Sometimes, she said, the sheriff posts on Facebook saying not to be alarmed. No one ever tells the community what chemicals are being burned.

“Our aim is to block the infrastructure that industry needs to cut our roots and establish its own roots here,” said Castillo, who this year launched a Texas branch of Chispa, a national Latino organizing project.

Elida Castillo on a city street near her home in Taft. Credit: Dylan Baddour

The port is pursuing its own $650 million expansion plan, including an 75-foot-deep channel running 11 miles into the Gulf to enable the world’s largest oil tankers to cross Corpus Christi Bay. A colossal, new billion-dollar bridge (by the same builders of a bridge that collapsed in Florida in 2018) will allow them into Corpus Christi Harbor and its port.

The two desalination plants proposed by the port would produce up to 80 million gallons a day.

The port declined to answer questions about projects in the pipeline, industrial water demand projections or plans for desalination.

Port CEO Sean Strawbridge, who came to Corpus Christi seven years ago and made $650,000 in 2021, told a meeting of the Ingleside City Council in August last year that the port began pursuing desalination plans after he “got a call” from someone who “decided to invest here and they’ve got a large project going on. Basically said, ‘What the heck is going on with your water situation down there?’ And the port commission decided to take a leadership role.”

A Century of Rising Salinity

Whether the port and the city ultimately get the permits they need for their desalination plants will depend upon forthcoming environmental assessments of Corpus Christi Bay, where the deadly effects of rising salinity are not theoretical—they are the lived experience.

These placid, shallow waters, sheltered from the Gulf by more than 200 miles of barrier island, once teemed with shrimp and oysters that had nourished bayside communities for thousands of years. Today dolphins still splash and great herons still stalk the wetlands, but the bounty of shellfish is gone.

In Nueces Bay, an inland appendage of Corpus Christi Bay, oysters died off in the late 1930s. Two dams on the Nueces River, and two railroads across its delta, were reducing freshwater flows.

Mullet swim in the shallow water of Corpus Christi Bay near Ingleside. Credit: Dylan Baddour

A great egret hunts while crude oil tanks at a trio of new export terminals stand on the far shore of Corpus Christi Bay. Credit: Dylan Baddour

“Oysters did not come back,” said a 2011 report from the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M. “Because the salinities were too high.”

Fifty years later, the shrimp were vanishing too. Two much larger dams stopped any freshwater at all from reaching the bays, turning Nueces from vibrant river delta to a shallow, stagnant mudflat where evaporation leaves extra-salty water and few living things.

“It was saltier than seawater,” said Montagna. “It became evident that the bay wasn’t producing shrimp or oysters anymore.”

The bays, formed by rivers that flowed to the ocean until the 21st Century, distinguish Texas’ coast from the successful examples of seawater desalination in California, where plants release brine into the deep, open Pacific. In Corpus Christi, developers want to discharge into a shallow, almost stagnant body. It takes one year for the contents of Corpus Christi Bay to be replaced by new water, Montagna said. The brine is going to accumulate, he said.

Keep Environmental Journalism AliveICN provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going.Donate Now